“You want to be joined, and you want to join.”

Hannah Brooks-Motl is a poet, editor, and scholar. She grew up in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, about thirty miles from Blackhawk Island, where poet Lorine Niedecker lived for most of her life. As a child and adolescent, Hannah spent many days on her family’s farm in northwestern Illinois—watching horses, playing cards. Parts of this history surface in Earth (The Song Cave, 2019), her most recent book of poems, in which “Creation gathers my filth & your filth … Pleasurable scales of wheat lands & corn lands & edge / former companions through the spider’s web.”

The author of the previous poetry collections M (The Song Cave, 2015), and The New Years (Rescue Press, 2014), Hannah was the poetry editor of the Chicago Review from 2016–2019 and is currently an assistant acquisitions editor for Amherst College Press and Lever Press. With Stephanie Burt, she helped edit Randall Jarrell on W.H. Auden (2005). She earned an MFA from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and a PhD from the University of Chicago. Her poems, essays, and scholarship have appeared in journals such as the Cambridge Literary Review, jubilat, and Modernism/modernity, among others.

I have known Hannah—as fellow artist, friend, and chosen family member—since September 2009, our first fall in graduate school at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She is a master of deep, long-term relationships—with texts, towns, genres, people. She lives, reads, and writes awake to Niedecker’s “wild and wavy event / now chintz at the window,” absorbed by the spiritual and intellectual lushness, vitality, and evolution of individual voices, the ways they may work together or clash, travel through time. In a review of Earth in Adroit Journal, Jonathan Suhr writes that in this collection, “The self becomes a referential object defined by its relations to definitions that are also always changing: society, home, family, poetry, memory.”

In Tupelo Quarterly, critic Henk Rossouw describes Hannah’s poem “Capitol” as generating a “tone that oscillates between critique and a careful hope vested in the idea that ‘the future is hidden’.”

I spoke with Hannah about Earth over Zoom in February 2020, a couple of weeks before The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, and video conferencing became a primary, if not compulsory, means of communication.

—Emily Hunt

THE BELIEVER: I know Earth went through several iterations before the book was finalized. I’m curious about your revision process and the evolution of the manuscript.

HANNAH BROOKS-MOTL: For years I wasn’t sure anything was headed anywhere. Writing M had been a really contained process, all about reading and responding and dialoguing with a set text or series of texts. It took a long time to figure out how to write a poem that didn’t do that. I wrote a bunch of one- or two- page recognizably lyric poems. And then the long poem “Virtue Theory” arrived. The manuscript kept starting and stopping until you got to that poem, which is this immersive, almost kind of novelistic experience.

I played the cello when I was younger and I continue to play the Bach suites which have different parts or sections, a waltz might be in there but so is a prelude, allemande, sarabande, all in the same key. I went back and thought about the poems not as isolated individual units, but as things that were in conversation with one another through something that might be like a content, but was also much more tonal—certain colors or moods or rhythms. I remade the book according to these principles.

BLVR: I definitely see this in your work. Your description makes me think of Earth’s epigraph: “Then must be realized no harmony but a system of discrepancies beautiful as the rotted peach.”

HBM: That quote is from Marguerite Young’s first prose book, Angel in the Forest. She started as a poet and then she wrote this historiography of two utopian communities that had been founded in the same town in Indiana, called New Harmony.

BLVR: Oh wow, New Harmony! I love that name.

HBM: It’s an amazing book. All of Young’s work is obsessed with utopia and our failures to achieve utopia. That quote includes the idea of harmony, but also of discrepancy, which is really fundamental, I think, to a lot of the poems in Earth. Things can hang together, but also not be the same, or be jarring. The idea is that you’re constantly oscillating between these attitudes and positions. In rethinking the book, I was working towards a place where things made sense, but were also dissonant, and that dissonance was part of the sense they were making.

BLVR: Right. You mentioned oscillation. I feel that flexibility in your poems. They don’t necessarily land as discrete individuals and stay put or static—they’re all moving in this kind of … not necessarily storm, but system, together.

HBM: I like the feeling that you can wander around in poems and that poems are capable of wandering around in you. I’m thinking also of the title, Earth. This place we all share that shares us. A kind of reciprocity that increasingly we need to be cognizant of in every moment. I wrote the book as a PhD student and that is also clearly present. [Laughs] My dissertation was on pastoral, which I was trying to argue was not just, although it definitely can be, a genre that provides ideological cover for retrograde politics. For me, pastoral ended up being less focused on the future—in the way that utopia is—and more concerned with how we adjust to now, to the present moment, or the ways that even within the present there can be pockets or margins that are unexplored and that might lead us into different modalities or ways of being with one another. I called Earth the B-side to my dissertation.

BLVR: That makes total sense.

HBM: And I think in the quote on the back of the book (“been reading / this was supposed to last / for eternity. // all theories of life now breached whereas/ we. come from nowhere. / it’s a commune.”), there’s all of that, right? The idea that reading is something that occupies an individual’s life and, especially in a PhD program, can feel interminable. For me that line “all theories of life now breached” is a gesture toward a very contemporary reckoning. The ways we’ve organized ourselves and thought we knew how to live no longer hold. We have to come up with new philosophies, new forms, new poetries.

BLVR: That sense of starting over with this mess behind us. Living in the mess.

HBM: Total mess, yeah.

BLVR: You talked about Marguerite Young, and the presence of all of these voices in your studies as you were completing your PhD. You’ve always had these kind of long-term relationships with writers, in the time I’ve known you. You routinely spend months or years tapping into the energy of individual dead writers and their living texts. I remember your chapters with Emerson, Laura Riding Jackson, W.S. Graham, Montaigne, of course, and many others. You’d show up in a room, and I’d feel these writers with you, in spirit, kind of buzzing there. Their voices would surface through your thoughts and stories from the day. And it was contagious! I couldn’t resist reading Laura Riding after hearing you talk about her. I remember exactly where I was—on a porch in Northampton, Massachusetts—when I read her lines, “As if the slow death were my own: / Weather is the dead at the hard school” for the first time. Are there other writers that have felt really crucial to the development of this book? Iris Murdoch also shows up in Earth, in various ways. You mention her in your acknowledgments.

HBM: I love this memory! Are porches the best place to read poetry? I think maybe. I should say that I enjoy philosophy as a very untutored, amateur reader of it. Murdoch’s philosophical work is, in part, about the ways that art and literature give us some sense of a transcendent good or way of being in the world and orientating ourselves and our behaviors towards a better version of who we are and who we can be together. Paul Valéry said, “There is no theory that is not a fragment, carefully prepared, of some autobiography.” This position or attitude became very important to me, and I think “Virtue Theory” somehow rhymes with Valéry’s insight. The poem is trying to have a thought that is the fragment of my autobiography. Or exist as a biography that’s full of thinking.

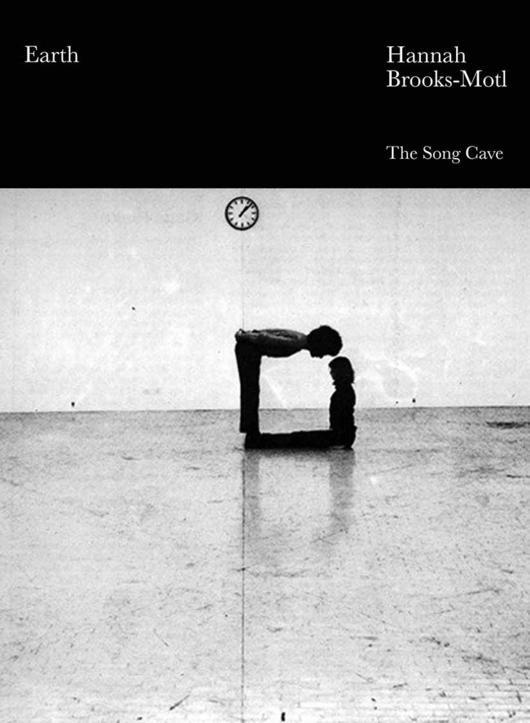

BLVR: I love thinking about a whole poem rhyming with a quote. That’s beautiful. Can we talk about the amazing cover image—how you stumbled across it, and why it felt right? The form of those two dancers really looks like a letter.

HBM: Earth’s cover is a photo from a performance by a German artist named Klaus Rinke from the 70s. The bodies do look like a letter or symbol. But, also, they’re only paused in that position—somebody’s going to stand up, somebody’s going to get up off the floor. They are never in isolation, never stuck or stopped, but always in this movement or gesture towards continuance and furtherance.

BLVR: Yeah. There’s the implicit possibility that they’re about to move. And you yourself are a dancer; you have a relationship to dance that is really important, maybe as important as reading has been to the book?

HBM: Like philosophy, dance is something I’m very much an amateur in, and that feels really freeing and exciting, to just bracket any question of mastery. I’m never going to be a professional dancer; I get to explore. Duncan dance, the dance I studied in Chicago, is unique because it’s really mediated by language. In certain ways, all dance is. When you go into a dance class, there is a specific vocabulary that’s being used, an idiolect spoken. A movement is described to you, and you’re trying to both process the words with your mind and do the thing with your body. The movement will sometimes inspire an emotion, and that becomes part of the crucible of the activity. In Duncan, the movements all come with this language that gets passed down from dancer to dancer through generations. Movement and language are operating outside of ordinary discourse in this very special way. If you’re in a contemporary dance class, a turn is a turn, you step onto your left foot or your right. In ballet, of course, there’s a very codified semiotic system of French, a jeté is a leap, and a frappe is this other thing. In Duncan you’re often trying to be language and movement that have some connection to myth or the natural world.

That new experience of language was hugely influential as I was writing Earth. Duncan is very much a community dance form. A lot of my relationship to it was also dancing with a group of women who ranged in age from 13 to 70, who had all levels of ability, all different kinds of life experiences. Being in a group like that, and being bodies together, I mean, again, I’m thinking of the commune. My experience of writing the book and living the book, and hopefully an experience that the book communicates, is that there may be these other possibilities of how to be together.

BLVR: I’m thinking of the word “welcoming.” The book as actively welcoming.

HBM: Yes! In Duncan we do a “calling gesture.” You first look at the person or entity you’re interested in, are made curious about, and then you reach out your hand, and you call. In the call, you do a huge arc and sweep. [She demonstrates.] You’re creating this circle, and you’re inviting. The intention is to actually invite, that’s important. You’re not just doing it as a shape or a pretty gesture. You want to be joined, and you want to join.

BLVR: This book feels so not isolated. It pulls in and includes so many voices, and there’s also a sense, in the form, that a reader can get swept in at any point in the progression of poems, or that there’s a place for every reader, maybe. Something about the space on the page, the wideness and length of many of the poems, and their velocity, feels like dance, and this kind of gesture of the call that you’re describing. And even just the openness of the title, EARTH! That scope that’s established right from the start. That scale and spaciousness.

HBM: The title poem in the book, which is actually the shortest, is only six lines, and it’s always been called “Earth.” I realized that this short poem contained everything in the book, and that was its title.

BLVR: Let me pull that poem up. There’s this line, “Could u find a home,” which also brings the commune and sense of community or belonging to mind.

HBM: The poem versioned out of a much longer, less oblique meditation about my brother. All of my work, but maybe particularly Earth, thinks about privilege. Privilege is foundational to how one understands their own existence and it’s particularly important to how I understand mine. This is true perhaps especially in families marked by disability or illness or addiction… My own existence, the basic fact of it, happened and continues happening in relation to another who is radically dissimilar to myself. There’s another Murdoch quote I’m thinking of. She talks about art as helping us to negotiate something like various dissimilar others—art entails “freedom as an exercise of the imagination in an unreconciled conflict of dissimilar beings.” I like thinking about dissimilarity rather than difference, because difference can often, I think, signal some unbridgeable gap or gulf. It’s also so connected to “same.” And nothing is the same as anything. It sticks you in this impossible conundrum that you can’t move out of. Whereas to think similarity and dissimilarity is to be able to find overlaps and connections and make distinctions that I think maybe you can’t when you’re stuck in a vocabulary of sameness and difference. It makes me think of the Paul Goodman quote in the last poem. “Meaning and confusion are both beautiful.”

BLVR: Yeah, confusion can be painful, but also fertile.

HBM: Books are restrictive, in their way. They insist on a final version. Earth is in some ways trying to both work toward that pleasure of final statement, while at the same time hold in tension the fact that nothing’s over, nothing ends, the dead don’t die, nobody’s cured. There are these ways in which all things are always true, and we’re always holding them, sometimes more happily than other times, sometimes more gracefully or adroitly than other times.

BLVR: Right. Yeah. I’ve always loved the Virginia Woolf sentence, “The other lighthouse was true too.”

[“No, the other was also the Lighthouse. For nothing was simply one thing. The other lighthouse was true too.”]

HBM: Oh yeah! Totally.

BLVR: Both truths are true. And that’s both clarifying and confusing.

HBM: Yeah.

BLVR: I know you’ve spent much time with Gertrude Stein these past few years, too. I saw you do a performance that worked with one of her pieces. What was that process of crafting a performance like? Is Stein also living somewhere in Earth?

HBM: My friend Ingrid Becker and I choreographed a movement study using Duncan vocabularies to Stein’s portrait of Duncan called “Orta or One Dancing.” It was the most legibly collaborative art thing I’ve ever done with another person. I feel like I’m always collaborating with you when I sit down to write a poem, and Dan [Bevacqua] and I collaborate in a way through all our writing. But with Ingrid, it really looked like what we think of as artistic “collaboration.”

BLVR: Right.

HBM: That experience was definitely one of having to be open to another person, to figure out very basic things together, because we weren’t that great of Duncan dancers at the time. It was like, limits, what can we do that will look good? [Laughs] That shows up in the book in what I hope is its openness to or interest in experiences that the poems themselves are intimating but are not ever being definite or closed down about. We also read the piece and used the reading as a soundtrack. Stein’s uses “one” over and over and over. And there’s that poem in Earth, “Parable” that—I hadn’t even it put it together until Dan read it, and he was like, “Oh this is like Stein, ‘the one, the one being one’”—

BLVR: I love the phrase “time was touchy” in that poem. What are you working on now? You recently moved from Chicago back to Western Massachusetts. Have there been any shifts in your writing/thinking/reading processes?

HBM: I write now really early in the mornings by hand, in part because I have this new job and I have to. But I’m also really starting to enjoy getting up at four or five a.m. and writing for an hour in the dark, bent over—it’s like a prayer kind of thing.

BLVR: Yeah.

HBM: And there’s something about handwriting for me right now—I feel like something is opening for me with it. I got to see Dickinson’s Master letters, because we did this photoshoot for Amherst College Press, where I work now.

BLVR: Amazing.

HBM: Also some of her fascicles. Her line is the length of her page—the limits of the poem are physical, material. It was so striking for me to actually see these documents. Handwriting is ancient, also for many of us still our first connection with using our bodies to write. The feeling of the hand traveling across the page into unknown space is one way to access earlier habits and modes of being. I’m never quite in control of what movement my hand is going to make next. I do a lot of waiting, and sometimes what arrives is dream content, sometimes a memory or what happened the day before, something I’ve read or I’m reading. I’m figuring what to do with and inside the limits of the page, that physical space. The way I write is by figuring out new limits, like with the Stein performance. Each book comes from some assembly of limits and limitations that I then try to work within, and figure out my way around.

BLVR: It’s obviously easy to locate one of those limits with M—you were working specifically with Montaigne’s essays. Is it possible for you to identify or articulate some of the limits you set out with in writing Earth? Or arrived at as you wrote?

HBM: It became clear or clearer to me. I was frustrated with poetry. I think that comes across. We write in these genres because we depend on them to make certain things legible to readers, and we rely on their associations and conventions and histories. But that reliance can sometimes occasion or elicit predictable reactions. I’m nervous when the poem just wants to activate that response, the recognition that it was in a sense made to receive. So some poems in the book struggle against that. I was exhausted by conventions even as I was figuring out how much I rely on them and we all rely on them.

The limits I was confronting also had to do with my own experience, my family and their histories—characterological limits, in a way. I think of that line from “Going” where it’s like “Ownership was impossible!” The limits of our fantasies about what it’s possible to own or to feel about ourselves and others are part of the book, too.