As someone who has been more or less fixated on death since I was a child, I am a fan of children’s books about death, and as a parent, have mourned the fact that there is a dearth of them—or at least a dearth of ones I really like.

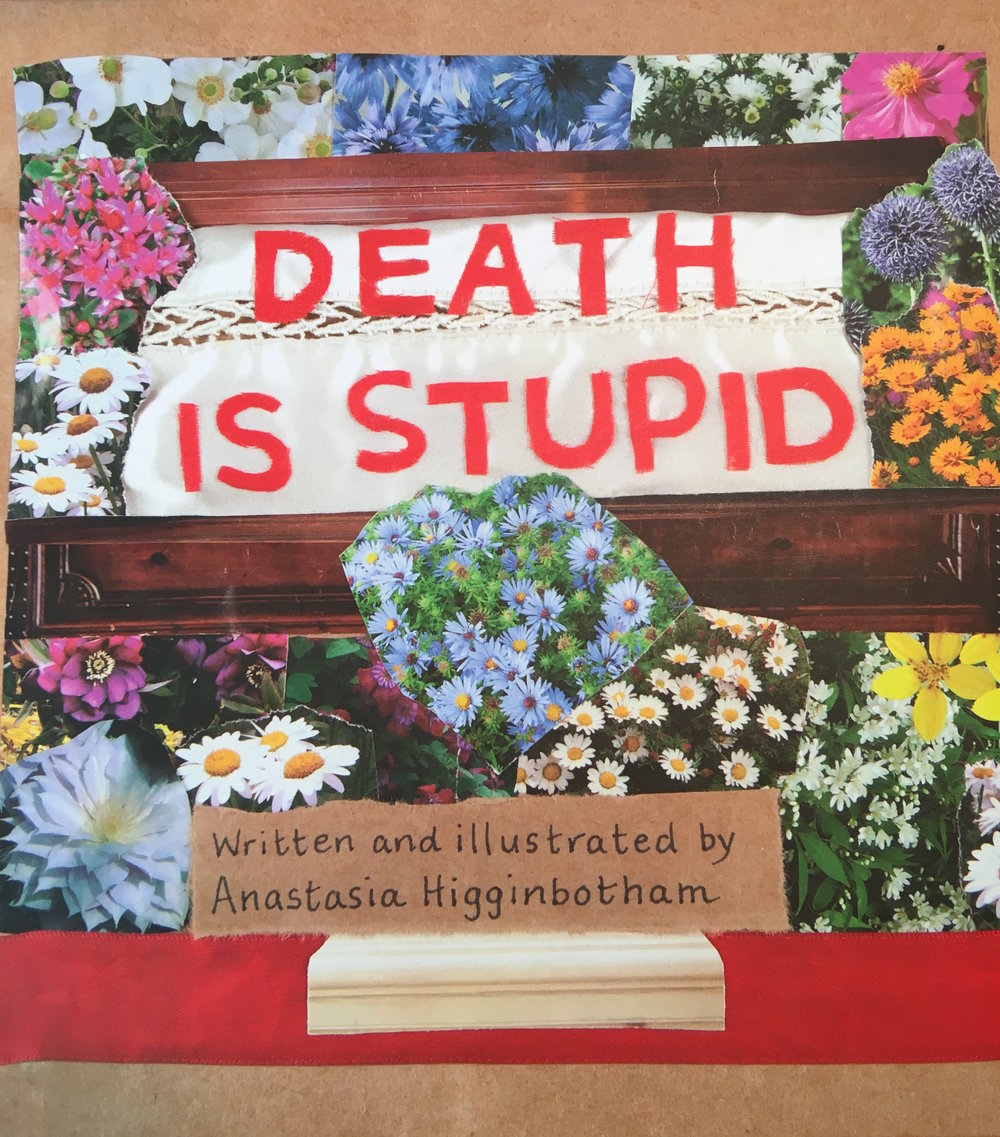

When I first saw Death Is Stupid by Anastasia Higginbotham at a party, I was taken with its perfect title and the way that title worked with the brightly-colored, collage-style cover. I took a picture of it so I could go and buy it later, which is how I found out that the book is one in a series called Ordinary Terrible Things, published by The Feminist Press.

I bought all three books thus far released in the series: Divorce Is The Worst, Death Is Stupid, and Tell Me About Sex, Grandma, and as I read them, I admired how Higginbotham neatly smashed common expectations about what children’s books do, particularly those that deal with difficult subjects.

Parents are located largely offstage in these books—I am reminded of the way that Peanuts creator Charles Schulz rendered the adult voices in his classic children’s films unintelligible—and children are depicted making their way through painful situations in ways that seemed to me startlingly real as well as radically generous to children. I sought out Higginbotham and spoke to her in her Brooklyn studio about her work and how it came to be.

—Amy Fusselman

THE BELIEVER: Tell me about the genesis of your children’s book series, Ordinary Terrible Things. I love how the title of the series undercuts a lot of what often happens in the children’s book genre, where terrible things are presented as unusual or extraordinary. How did you come to devoting yourself creatively to this perspective?

ANASTASIA HIGGINBOTHAM: Recently I read a quote attributed to Edith Wharton that said: “Half the trouble in life is caused by pretending there isn’t any.” I love that so much. That is the whole point of this series. All of the serious problems I’ve faced as an adult—self-hating behaviors, debilitating sadness about injustice, f’d up romantic relationships, sexual harassment at work (by women and men), my violent temper, etc.—traces directly back to the unaddressed, ordinary, terrible things that happened when I was a kid.

Events like divorce, death, or an incident of sexual abuse, for example, could be approached as difficult and painful times in a child’s life. But they often get ignored instead, made light of, or flat-out denied by grown-ups who see children’s lives as simple and see children’s pain as less than real. But something that started out as trouble, over time, becomes trauma. I believe this accounts for why so many adults cannot bear witness to their children’s heartbreaks. To some degree, every generation is recovering, or failing to recover, from some ordinary, terrible thing that could have been dealt with, compassionately, a long time ago. It makes it hard to be fully there for our own kids.

In my books, that is what I am trying to do for kids: be there. Books that see you in a loving way can be a stand-in when the people in your life are too distracted to see you or, for any number of reasons, just can’t.

BLVR: The title of your first book in the series, Divorce Is the Worst contrasts nicely with Judy Blume’s It’s Not the End of the World. Have you read Blume’s book or did you have it in mind at all when working on yours?

AH: I was too hurt by my own parents’ divorce and offended by the cheerfulness other people’s divorce books to read any of them before I made mine. But I read a few after. Judy Blume and I reach the same basic conclusion: Your parents will do what they do. The important thing is getting you through it, whole. The difference is Blume centers her book in an adult perspective, since adults know that life can get a lot worse than a divorce. Which is hilarious when you think about saying that to a child to cheer them up.

But see, part of the problem with my title, Divorce Is the Worst, is that people think that’s the adult author’s voice, defining the situation for the child the way most children’s books do. But it’s the child’s. My books give kids permission to be really upset and take it hard and take it personally. Part of what I’m doing with my title is offering a statement so unequivocal and outrageous, the child might laugh and think, Geez, it’s not that bad. But they’re interested now, because, If the adult who made this book is saying divorce IS a big deal, and I am navigating my own parents’ divorce pretty well, then maybe I am a badass. Which, indeed they are.

BLVR: What made you want to address sex in the Ordinary, Terrible series?

AH: My son asked me what “sexy” means and what sex is when he was six, and all the answers that came into my mind were wrong. “It’s when a man and a woman…” “It’s when two people…” “It’s when you love someone…” I mean, wrong, wrong, wrong. I realized I wanted to introduce sex to him as something he was born with that would grow up with him. It’s not something outside of him that “will happen” in adolescence, in adulthood, in love, or in marriage. It’s in two-year-olds and 92-year-olds. It’s totally individual. It’s totally yours.

We live in this culture that is obsessed with sex and obsessed with putting barriers around sex—but especially around kids and sex. And that is bullshit. The barriers should be around adults. Instead of telling kids to watch out for molesters and tell us if someone “touches” them, we should be reminding adults what the rules are and telling kids from the start: Adults know good and damn well they’re not supposed to have sex with kids. That way, at the very least, our kids will waste no time wondering who is to blame. But we lay the whole burden on kids. We tell them to wait, abstain, avoid, or approach with extreme caution. They’re taught about sex in a context that threatens them with pregnancy, disease, abandonment, and violence. It’s the worst possible way we could go about it. And everyone who isn’t teaching sex this way—marvelous, wise people—is under intense pressure. They’re challenging something deeply ingrained in America’s psyche about sex being, in the very same moment, deeply shameful and completely irresistible. Sex could be a lot saner than that.

With Tell Me About Sex, Grandma I wanted to offer the sparest and most spacious definition of what sex is, leaving plenty of room for a very young child of any gender to imagine becoming, over the course of their entire life, a person who gets to make choices about how they want to experience their own sexuality.

BLVR: I had some teenagers at my apartment who read Tell Me About Sex, Grandma and thought it was fantastic. What is the ideal age for your books, do you think?

AH: Those teenagers are the perfect age! And so is a six-year-old who accidentally found porn, and the all the eight-year-olds who want to know why the joke is funny. And the 25-year-old who’s finally gotten enough distance from his strict religious family to fall in love with a man. And the 40-year-old who is finally confronting the incest in her past that keeps ruining her life. And the 75-year-old who is newly aware of how liberating and amazing sex can be and wants to be that Grandma who is trusted to answer a child’s question honestly, taking the child’s lead, making space for the child to just be who they are.

BLVR: How many titles will there be in the Ordinary, Terrible series? What is the next one?

AH: I’d like to keep going until my hands are too shaky to use such tiny scissors and my eyesight is too blurry to draw such tiny hands.

The next book is called Not My Idea and deals with white supremacy. It comes out in Fall 2018 as the debut title from Dottir Press, which was founded by author, filmmaker, and recent publisher/director of the Feminist Press, Jennifer Baumgardner.

In the new book, the white child at the center of the story looks up from a massive pile of homework just in time to see, on the screen his mother watches, a white police officer freaking out and then shooting a person with brown skin whose hands are up, someone who was totally de-escalating and cooperating, and is a threat to no one except inside the warped mind of whiteness. When the child asks why the officer shot, his mother deflects. She changes the subject. He has to find another way to get his questions answered.

BLVR: What books or artists have inspired you in this work?

AH: Lynda Barry’s books and comics have provided most of my art education, as well as most of my recovery from my own childhood. Matt Groening’s Life In Hell series had a huge impact on me, in particular, the ones where Bongo cowers in the gigantic shadow of a parental figure and one called: Those Childhood Favorites We Read Again and Again and Again, featuring imaginary titles like: The Father Whom the Whole Family Was Afraid Of and The Mother Who Was Sick All the Time and Made Her Daughter Feel Guilty. Jim Henson and the writers from the Old School Sesame Street episodes (which I’ve rewatched a million times as an adult) helped shape my voice. The way those Muppets never talked down to kids in the 70s, the tenderness, directness and wild humor of some of those skits and one-on-one moments with kids, has imprinted deep in my brain.

The artists I study today are all ones I never knew about until I became an adult: Romare Bearden, Patricia Polacco, Ezra Jack Keats, Faith Ringgold, Tomie dePaola, and illustrators on the scene right now, Sean Qualls, Javaka Steptoe, Bryan Collier, Christiane Krömer, Cassandra Gillens.

BLVR: You are giving a talk soon. Do you often give talks at schools or bookstores? What is your talk about?

AH: I’ll be talking on November 10 at Stories Bookshop in Brooklyn, NY, about building resilience in children. I’m not a parenting expert and have all my own flaws as a parent, so I won’t be giving advice. What I will do is highlight some of the reasons and motivation to center the kids of my stories in such awful circumstances and then accompany them through it. There are specific places in the books where I give the child important information about their capacity to be present and aware during difficulty and heal from it.

I do give talks and visit schools and libraries. Sometimes this includes a collage-making workshop. I love doing it and kids and adults are usually hungry to talk about the ordinary, terrible things that have happened to them or someone they know. Everyone wants a book about their issue, which is fascinating because it means they can see, in my format, how they might exist in those brown pages and be loved and safe, even though their life is full of trouble. They can picture themselves right there, wearing a little jacket and ribbon hair.

BLVR: Tell me about your work in teaching self-defense to kids.

AH: For about 10 years I was an instructor for Prepare Inc., a company in New York City that teaches the IMPACT curriculum to adults and kids of all genders. They create real-life scenarios for kids to practice dealing with aggressive or intrusive behavior from their peers and adults, both strangers and the people closest to them. Kids learn to breathe, talk, and fight even when they are afraid and their adrenaline is pumping and heart is pounding. Once you learn something this way, it stays in your muscle memory.

Depending on how much time we have in a class, and what age the children are, we can work up to some pretty hard challenges. I particularly enjoyed, in our role plays with the kids, portraying adults in their lives who don’t listen, don’t believe them, and even blame them when they disclose something disturbing that happened to them—then I would pause and say, Now what? We’d strategize who to tell next (the principal? our other parent? a grandparent? a teacher?), and keep telling, until they found some adult who believed them and promised to take responsibility for their safety. To see children actually physically fight, yell no, and take on an adult who is threatening them was always thrilling. That was the most satisfying form of activism I have ever experienced. It became a job that was impossible for me to sustain once I had young children. So now I do this. Maybe someday I can go back to it.

Purchase a copy of the current issue of The Believer here, and subscribe today to receive the next six issues for $48.