Format: 320 pp., hardcover; Size: 5.25″ x 7.5″; Price: $26.00; Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Deceased Women Mentioned in the First Chapter: 13; Number of Works by Author Listed on Wikipedia: nine; Number of Ancient Greek Rhetoricians in the Book: one; Best Blurb: “Anne Boyer’s unflinching account of the market-driven brutality of American cancer care sits beside some of the most perceptive and beautiful writing about illness and pain that I have ever read.” Representative Passage: “Just as no one is born outside of history, no one dies a natural death. Death never quits, is both universal and not. It is distributed in disproportion, arrives by drone strikes and guns and husbands’ hands, is carried on the tiny backs of hospital-bred microbes, circulated in the storms raised by the new capitalist weather, arrives through a whisper of radiation instructing the mutation of a cell. It both cares who we are, and it doesn’t.”

Central Question: How can a writer tell a story about breast cancer in a way that admits not only her own narrative, but a politics of collective action—a deeper history?

Anne Boyer is a poet-cum-political economist, a master who studies women’s work and excels at describing the mental knots and material calculations that late-stage capitalist America creates for its poor and marginalized citizens. In books like the prose-poetry memoir Garments Against Women and the experimental essay collection A Handbook of Disappointed Fate, Boyer interrogates what it means to survive in the American heartland as a woman, mother, and artist. Her writing reminds us that the fact that American women are sick, tired, overworked, underpaid, and dying at extraordinary rates in the United States is a historically constructed condition rather than a failure of self-will or determination.

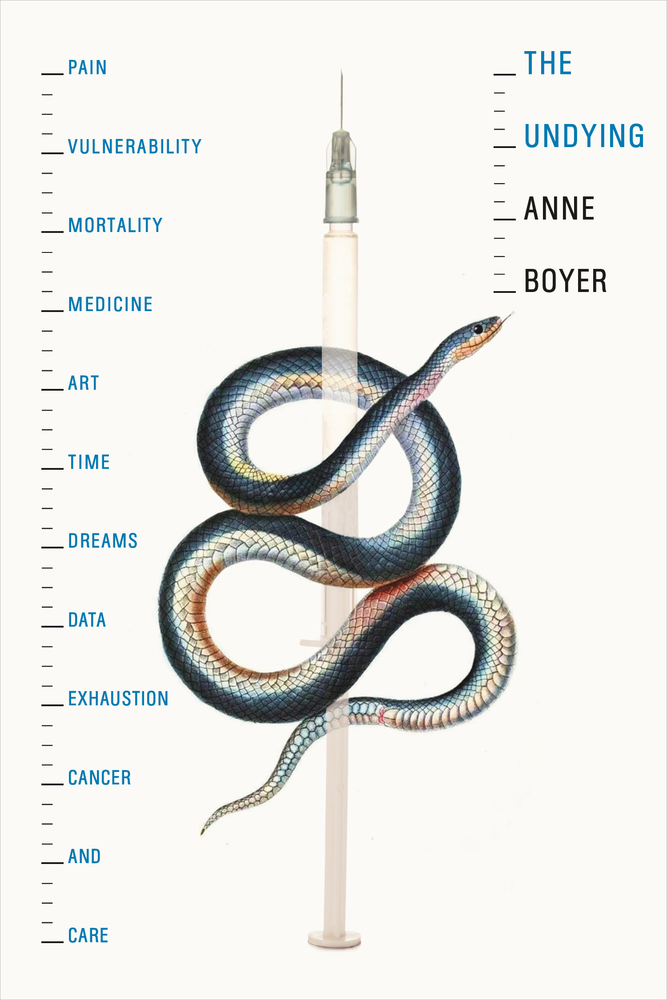

She continues this project in her latest book of essayistic prose, The Undying. We might call The Undying a breast-cancer memoir; it might be more accurately described as a poet’s attempt to analyze the pernicious cultural fictions that accompany breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in the public imagination. Unlike a memoirist, Boyer does not tell a story. Her work of critique privileges metaphor in conveying its message, and it aspires to literature, not testimony. Literature, as some writers, including the poet Carolyn Forché and the philosopher John Dewey, argue, does not represent experience, but creates it. Like Boyer’s previous books, The Undying uses literature itself as a space to ask: What happens when literature is not, following Aristotle, an imitation of “men in action”? What happens when, instead, it creates the experience of being one among many women who are subjected to extractive economic and legal systems designed by wealthy men? In a wry, oracular voice, she answers these questions by blending personal narrative, political discourse, historical investigation, and literary examination to reveal the political and economic structures that multiply suffering for patients. She seeks to separate art from artifice, and to demystify who holds power in our world.

In the book’s prologue, she invokes the stories of famous women writers who died from breast cancer, including Susan Sontag, Audre Lorde, Kathy Acker, and Eve Kofsky Sedgwick. She describes the formal problems that they—and she—faced in writing about breast cancer; one cannot assume that to write about the disease is to contribute positively to the project of “awareness,” Boyer says. Breast cancer’s ubiquity in our cultural discourse means it has become an illness onto which Americans project ideological narratives of individual struggle and triumph. Think: Innocent female victim falls ill with mysterious disease, struggles, suffers, fights and ultimately survives via neoliberal self-management—as Boyer puts it, “disease cured with compliance, 5k runs, organic green smoothies, and positive thought.” To the victors go the narrative spoils, she says. In defiance, she places the words of her deceased comrades early on to act as guardians of the text that follows.

She turns away from the language of “survivorship,” tied as it is to industries that profit from women’s stories of individual suffering. Instead, she turns to the many voices of those who did not “beat” cancer—those who did not “win”—suggesting that the warlike metaphors we use to discuss who lives and who dies from cancer are all wrong. She maps her methodology and aim in the book’s prologue:

To write only of oneself is not to write only of death, but under these conditions, to write more specifically of a type of death or deathlike state to which no politics, no collective action, no broader history might be admitted. Breast cancer’s industrial etiology, medicine’s misogynist and racist histories and practices, capitalism’s incredible machine of profit, and the unequal distribution by class of the suffering and death of breast cancer are omitted from breast cancer’s now-common literary form. To write only of oneself may be to write of death, but to write of death is to write of everyone.

The book aims to serve a collective political project. In writing about her experience with a type of cancer that is too often terminal, Boyer illuminates the social structures that shaped the deathlike state of her illness. To this end, The Undying is organized around a series of meditations on themes that follow the chronology of her cancer diagnosis and treatment. While these themes—which include the cancer pavilion, the sickbed, tears, wasted life, deathwatch, among others—track the stages of her illness, the bulk of each chapter focuses on the social structures and environments she encounters rather than the details of her personal story. She uses her experience as a poor, single woman diagnosed with a highly aggressive form of triple-negative breast cancer as the book’s frame, into which she threads her critiques of toxic American… well, everything. She examines our poisoned air, food, and water; the systemic violence perpetuated by pharmaceutical companies and for-profit medicine that disenfranchise the people they’re meant to serve; and the nefarious forms of social discourse that would posit health and healing as an entirely individual responsibility. For example, in writing about the structure of the cancer pavilion, Boyer points out that “all activity inside the pavilion is transient, abstracted, impermanent, dislocated. The sick and the partners, children, parents, friends, and volunteers who care for them are kept in circulation from floor to floor, chair to chair…. Cancer treatment appears organized for the maximum profit of someone—not the patients…. Money and mystification, not knowledge or ignorance, are its cardinal points.”

We dip into first-person reflections only intermittently throughout each chapter. We learn that Boyer tries to be the best-dressed person in the infusion room, replete in “thrift-store luxury,” wearing a large gold horseshoe brooch. “The nurses always praise the way I dress. I need that,” she tells us. And later, when her friend the poet Juliana Spahr comes to visit from California, they fill out prayer cards in the pavilion lobby and slide them into the shoe box that serves as a receptacle for people’s desperate wishes: “Please pray, we write, for American poetry.” These moments of intimacy are often humorous, a way to insist that this book was not written to elicit a readers’ pity, or compassion for Boyer as an individual patient, but to draw our attention outward, to the political and social structures that shape sickness. In many illness memoirs, we stay close to the first-person narrator throughout the story, becoming consumed by our own empathic responses to their struggles. Boyer resists this reading; her own experience is a touchstone rather than propeller. She is critical, and her critiques glint with truth. Yet, as someone whose mother died of breast cancer, I found that her quick forays into personal detail drew me closer to Boyer’s literary persona. I couldn’t help but care.

That said, some of Boyer’s most memorable writing emerges in her critique of the “pinkwashed” landscape of breast cancer survivorship. She notes, “breast cancer patients are supposed to be, as the titles of the guidebooks offer, “feisty, sexy, thinking, snarky women, or girls, or ladies, or whatever.” She also critiques the popular slogan “Fuck Cancer,” which is, I learn, the name of an American and Canadian nonprofit; it’s also a keyword that calls up an incredible 4,153 results on Etsy alone, with products ranging from tee-shirts and bracelets to wine glasses and socks. As she writes, “‘Fuck cancer’ is always the wrong slogan if for no other reason than that the cancer is your own body growing inside you, but also because ‘cancer’ is a historically specific, socially constructed imprecision and not an empirically established monolith. The whole time I’ve been writing about cancer, I’ve been writing about something that scientists agree doesn’t quite exist, at least not as one unified thing. Fuck white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’s ruinous carcinogenosphere would be a lot better, but it’s a difficult slogan to fit on a hat.” (Note: I was able to fit this slogan on a hat via an online corporate-swag platform. I could only buy them in units of twelve—email me if you want in.)

The book’s force then, comes from its complex form. Each chapter reads like a series of prose poems, and relies heavily on metaphor to explore its questions. Throughout The Undying, Boyer refers to the story of Aelius Aristides, a second-century Greek orator who lived for years at the temple of the god Asclepius in the hopes that by sleeping in sacred territory—and obeying the instructions of dreams—he would be cured of his mysterious illness. Aristides’ story becomes a framework that Boyer uses as a way to look at the bizarre, ritualistic practices the American medical-industrial complex inflicts on patients. With statistics as “an ulterior mysticism,” we now sleep “in the precincts of gods we have forgotten.” I interpret these gods as, among other things, the for-profit model of medicine wherein doctors and researchers must operate according to agendas set by private hospital owners, insurance companies, and the pharmaceutical industry’s bottom line. American healthcare has become a way of producing treatments (which are profitable) as opposed to helping people get well (which is not).

Boyer’s formal experimentation is what she asks readers to judge the book by at its close. And it is the book’s form that, if anything, could potentially deter some of those who need this work, people Boyer hopes to reach. She posted on Twitter this summer, before the book’s release:

“I swore to myself I wld do everything to get the work on cancer to as many ppl outside of literary culture/subcultures as I cld, but publicity & publication is so against my nature that mostly the attempt to go against myself has mostly just made me ill.”

“it’s hard to know if it is worth it. I want ppl to be able to get the book that use public libraries, that don’t follow literary news, that brush up casually against mainstream magazines & newspapers & might need what the book has in it.”

Her posts spoke to some of my own concerns while reading. The fragmented chapters can be disorienting: at times, in paragraphs dense with metaphor, critique, dream, and anecdote, I found it difficult to remember where I was in Boyer’s narrative timeline. This stylistic choice risks alienating readers who aren’t familiar with how to approach an “experimental” text. And, though Boyer wanted to avoid romanticizing what it’s like to be terribly sick via the illness memoir—claiming she “would rather write nothing at all than propagandize for the world as is”—I wonder if she at times underemphasizes some of her more common, relatable fears. She addresses this critique in the text itself: “If you don’t know me, you might think, too, that my illness was so precious it was merely a suffering for the sake of semiotics, that I sat in the infusion room thinking only of Ancient Rome.”

Will The Undying reach an audience that doesn’t already read “literary” books? And will a reader who doesn’t read literary nonfiction—especially one diagnosed with breast cancer looking for some way to grapple with her experience—find something she needs here? I hope so, because while Boyer’s writing requires the reader’s submission to its unfamiliar form, it also asks us to grapple with how incredibly messed up it is that American medicine and economics shape the structures of our daily lives, often in a way that prevents us from being able to name these structures—such as neoliberal capitalism, or for-profit medicine, or systemic racism, for example—clearly.

Boyer does her best to offer signposts as to how to navigate the book throughout. If you stay with her, the effect of her prose is astonishing. The book’s sections, which fragment into short essays like cells, multiplying and dividing, disorient the reader in a way that perhaps—following Forché—creates an experience of illness for the reader. The Undying can make someone who believes that American healthcare and the American economy today “works” feel sick: sick with the world, sick of it, even helpless and lost. For those of us who have lived amid America’s failures in healthcare and beyond, it’s a relief to hear this failure reckoned with in literature. Boyer describes the violence and confusion that public policy and history—mediated by racism, classism, and gender—inflict on our lives.

At the book’s end, Boyer concedes to a kind of failure: “I hate to accept, but do, that cancer’s near-criminal singularity means any work about it always resembles testimony.” At the close, The Undying gets personal, and stays there. But this personal testimony is not as singular as it seems; instead, it joins with voices of the dead authors invoked at the book’s beginning. It stands as one among many in a collective form of literary testimony.

“Enchantment is not the same as mystification,” Boyer tells us early in the book. “One is the ordinary magic of all that exists existing for its own sake, the other an insidious con. Mystification blurs the simple facts of the shared world to prevent us from changing it.” And so, if you do read The Undying as a failed collective call to arms, the book succeeds in a different collective project. It succeeds by existing as it is—an enchanting bit of restorative magic for its readers. “When I was at my lowest, what I needed most was art—not comfort—and so it was to get through cancer that I had to wish everything around me into aesthetic extremity,” she writes. Ultimately, the book does not comfort; nor does it tear down the toxic industries, rhetorical obfuscations, and violence of American for-profit medicine. Instead, it provides a record of one woman’s struggle to know, as Boyer writes, “if not the truth, then the weft of all competing lies.” Perhaps this is as close to truth as we can get.