It’s dangerous nowadays to attempt a two-week news-cleanse, as I intentionally attempted during a recent vacation retreat: you never know what you’ll have waiting for you when you get back home.

In my own case, what I had waiting, among many many other things, was the story about how Likudist parliamentarians in Jerusalem had passed themselves a new law summarily declaring Israel a “Jewish state,” in one fell swoop demoting the 20% of the country’s citizens who happen to be Arab to a nebulous second-class status, and the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians living under occupation to some sort of status well below that. The law seemed to have been drafted in anxious response to the growing awareness of the fact that, what with negotiations toward a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict stalled if not permanently upended by an endlessly compounding array of government-implemented so-called “facts on the ground,” the Arab portion of the population of those under Israeli suzerainty was fast approaching a majority of all those residing between the Jordanian border and the Mediterranean sea.

Anyway, shortly after the vote, triumphant parliamentarians were photographed by Olivier Fitoussi of the AP celebrating the moment by casting themselves in giddy selfies alongside their smugly self-satisfied leader, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu…

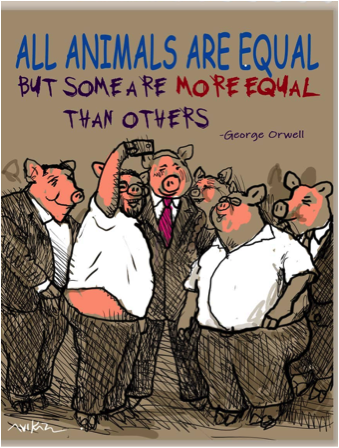

…which in turn led to veteran cartoonist Avi Katz referencing George Orwell in his sly skewering of the image in the pages of Jerusalem Report, an Israeli English-language fortnightly owned by the Jerusalem Post…

…which in turn got the cartoonist, Katz, who had been contributing material to the Jerusalem Post for three decades, summarily fired. Supposedly for having perpetrated such a baldly anti-Semitic image, pork of course being trayf, which is to say decidedly not kosher, as things were piously explained…

…which of course missed (or more likely conspicuously misconstrued) the entire purport of Katz’s Orwellian reference, for in the anti-Stalinist allegory of Animal Farm, the pigs who had led the farm-animals in the uprising against their cruel human masters thereafter slowly transmogrified themselves, assuming human traits and donning human clothes and indulging in all manner of human satisfactions, until by the book’s famous ending, “No question, now, what had happened to the faces of the pigs. The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.” If Orwell had been suggesting that Stalinist communists had transformed themselves into an evil indistinguishable from the capitalist oppressors they’d once opposed, Katz seemed to be suggesting that Zionism itself had now taken on the full trappings of the European fascisms against...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in