Judging by the popularity of the Jurassic Park franchise—five feature films, with a sixth blockbuster scheduled for 2021, three “Lego” Jurassic Park shorts, various theme-park attractions, some forty-six theme-related video games, even a Jurassic Park Crunch Yogurt—dinosaurs (once the province of paleontologists and children) have had a stranglehold on our collective imagination for more than a quarter century. Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel sold more than nine million copies; three years later, the first mega-film, directed by Steven Spielberg, became the second highest-grossing film of all time, earning over $1 billion worldwide.

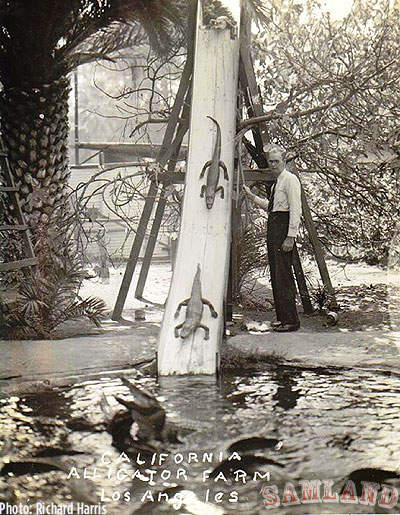

Though less enormous, less voracious, and lacking dramatic soundtracks to pave their entrances and exits, formidable flesh-and-blood, non-animatronic prehistorics do actually walk among us.

Alligators have been around for some 200 million years, which is 135 million years longer than their dino contemporaries. It wasn’t until the twentieth century that that extraordinary longevity was threatened. Pretty impressive, given all the environmental changes that have ensued in the interim, and the fact that their brains are about the size of a walnut.

Our human ancestors began crafting crude stone tools about 2.5 million years ago.

Biologically, Crocodilia (alligators, crocodiles, caimans, gharials) are closer to birds, dinosaurs to snakes and lizards, but they share a common ancestry. Fossils reveal that back in the day, some alligators grew to nearly forty feet in length, weighing in at 8.5 tons. Simply put, Crocodilia are the closest living examples of the Jurassic’s ancient denizens.

“Dinosaurs and man, two species separated by 65 million years of evolution, have just been suddenly thrown back into the mix together,” notes Jeff Goldblum’s character, Alan Grant, in the 1993 film. “How can we possibly have the slightest idea what to expect?”

In the case of their alligator cousins, it wasn’t just suddenly. Throughout the American south, they’ve always been pretty much unavoidable.

On the big screen, our relationship to Crichton’s creatures is set and predictable. We enjoy the terror they inspire from the dark safety of our upholstered seats. Alligators, in cinema, have always been as dependable in their villainy as Nazis. What better way to dispose of pesky early Christians or enemy Russian spies?

In the real world, the relationship of humans to ancient apex predators is far more complex.

In the mid-19th century, alligator oil was used to lubricate engines and machinery and sometimes recommended as a cure for various ailments; antebellum slaves often relied on alligator meat to supplement otherwise meager diets. But overall, North America’s largest reptile was considered vermin, best suited for target practice, until a Civil War leather shortage led...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in