Award received by author: 2011 Hudson Prize for Fiction; One of author’s occupations: programming director for the Bowery Poetry Club and Howl Arts; Number of poetry collections author has written: two; Non-literary publication in which author has published work: Mathematics Magazine; Representative sentence: “As I went, the city drew in close, the slate and marble streets merged with the overcast sky and the reflectionless windows and the mobs in their faded uniforms, but my focus remained on the spots of red, each mark maintaining its perfect round shape, glistening, and refusing to be absorbed into the ground.”

Imagine a trail of blood: bright crimson drops stretched to either side of you across a vast backdrop of gray (gray pavement, gray city, gray institutional life). At one end is a man—bleeding and stunned, walking hopelessly, unable to explain himself or speak. At the other end, where the trail began, lies an answer, perhaps; approach it, though, and the man recedes, becomes a point, and eventually, his face burned into your memory, a fiction to be tracked in your mind.

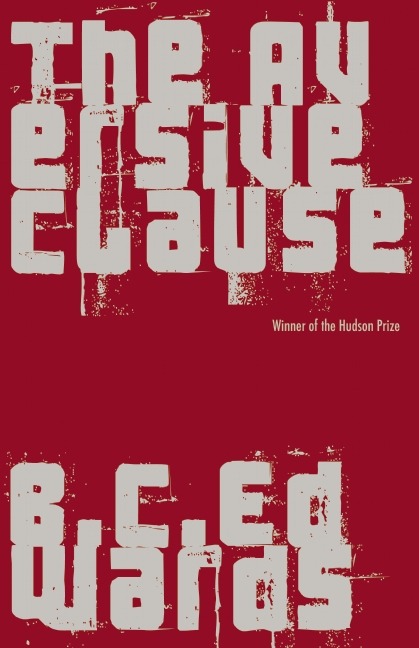

This is a bare-bones rundown of the eerie tale “Spots,” a scenario that perfectly captures the strange welding of the real and the fabricated in B. C. Edwards’ fine collection The Aversive Clause. The oblique and the imaginary are the author’s road to truth, while the purportedly real can seem, by turns, dream-filtered and insubstantial or emotionally dead. It’s through shifting, dubious vantage points that we catch wisps of being: the twinge of loss when everything is accounted for, say, or that peculiar sensation of standing outside of life, looking in.

“As I was walking down the street that afternoon I crossed paths with a man with blood pouring down his face,” the narrator begins. Losing the man in the crowd, he moves on, late for an urgent job interview. (The passersby, thoughts on their “obligations,” are silent.) It’s along the way, as he notes bloodspots trailing in the direction he’s headed, that the societal forces at work come to light for us: a looming police state and caste system, the narrator’s joblessness, his family’s dwindling tickets for rations. With his worn shoes, his “unironed and oil-stained” gray shirt, the narrator dangles perilously above his world’s lowest tier. And whether it’s the gloomy gray color scheme or the crowd’s inhuman silence, we quickly sense that this world is off-kilter, a place where apparitions might bob up like subconscious terrors, where bloodspots are the only objective evidence of the bleeder’s reality.

In the scene that follows, the narrative fabric grows more gossamer as a second story takes over. At the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in