Eda Yu on the Use of Gravity in Pop Culture

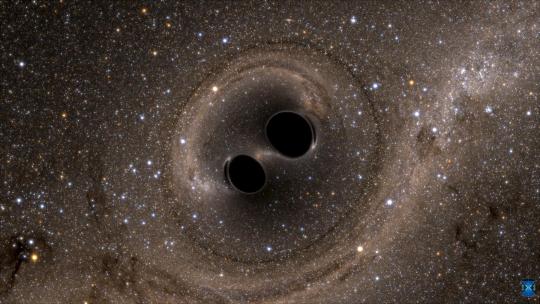

One point three billion light years away, two black holes collide. Both are around 30 times the mass of the sun, neither small nor supermassive, but these two black holes are, like all black holes, a prodigious kind of death: collapsed stars that are only able to be seen through the movement of their still-shining celestial counterparts. When they collide, they generate the most energetic event observed in the universe, changing the distance between the Earth and the sun by the width of a single atom. They also generate the first gravitational waves ever to be detected.

The popular conception of gravity is as a force that acts on us, an inescapable entity over which we have no control. But last September, when the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) collaborators detected gravitational waves, they confirmed the stunning malleability of space-time and the true role gravity plays in describing our universe’s celestial blanket of time and space. It seems we’ve been thinking about gravity all wrong.

Although we tend to think of time and space as constants, they are actually dynamic variables—elements that are constantly in flux, depending on the energy content of the universe. We are, in a sense, able to affect time and space as much as they are able to affect us. Contrary to popular belief, time does not simply progress in a linear fashion; instead, it encircles us, perhaps even giving way to the strength of our small bits of substance. As space-time yields to mass, curving snugly around matter, gravity measures that curve.

“A gravitational wave is a bending of space-time itself,” says Meg Millhouse, a PhD student at Montana State University and a member of the LIGO collaboration. In theory, gravitational waves are created when masses move and disturb space-time; a common example scientists employ is “a sheet of rubber” to represent space-time “and a bowling ball in the middle” to represent gravity.

The observation of gravitational waves has far-reaching, potent consequences, opening doors for further scientific advancements and fields of study, in addition to more comprehensively proving Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity. “The analogy [scientists] like to use a lot is that we’re now listening to the universe. It’s a totally different wave band, different spectrum. Before, we could only see the universe; now we can hear it, too,” Millhouse says.

The observation of gravitational waves has brought us a step closer to celestial enlightenment, but is this enormously powerful force even the same gravity we thought we knew? In pop culture, gravity is often portrayed as a force that draws us to a romantic interest against our will. In Muse’s “Supermassive Black Hole,”...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in