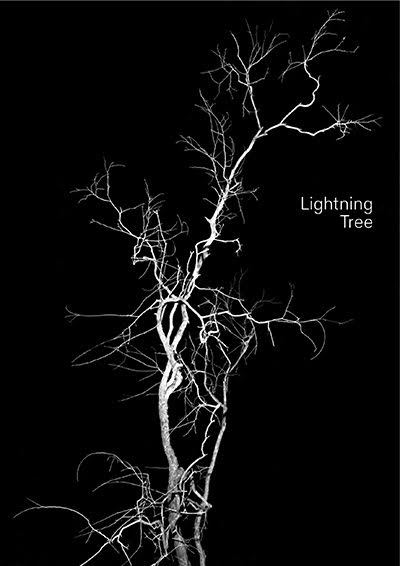

Bucky Miller on Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs’ Lightning Tree and Mr. Thingy

Trees are nature’s grand manifestation of beauty and true chaos. Everything is connected to trees, history, memory, past, and future. One day we started to look at our archive like looking into a forest. This publication is one tree in this forest. The tree that was singled out and struck by lightning.

—Back cover copy from Lightning Tree

The house where I was born had a big tree stump in the front yard. That’s what I want to say, but it’s not exactly right. My memory locates a cracked, gray stump, about three feet in circumference, just off the front porch in a spread of brittle-to-dead yellow grass—the standard lawn in Phoenix. At Christmas the stump was decorated, and at Easter it hid eggs. I remember playing on the stump, being bitten by twenty fire ants and then being angry at the stump. I was told it was a home for leprechauns. I remember, shortly before my family moved, my mother giving me an oral history of the stump: naturally it was once a tree, and when I was an infant that tree was struck by lightning and burst into flames. We watched it burn as a family. The fire department came; the tree was doused but dead and soon after, cut down with a chainsaw.

So, more accurately, I was born in a house with a big tree in the front yard, and even though I’ve seen the tree—immolated!—I can only summon a reasonably faithful image of the stump. I was too young for the tree. The tree is a ghost. Any description of the tree would be nothing but a product of my imagination, some amalgam probably closer to the oaks I see out the window as I write rather than the acacia or whatever it actually was. My images of the fire are from Hollywood; flames a color that only appears on film or video; odorless, heatless; a burning tree either far more or far less dramatic than the actual event had to have been.

Then again, it could have happened just as I’m picturing it. It’s not something I think about very often; the tree came back to me on maybe my sixth or seventh look through Tayio and Nico’s newest publication, Lightning Tree, and even then, beyond the title, I’m not totally sure why it did. You might expect a book of photographs titled Lightning Tree to present a catalog of well-defined pictures showing trees that had been struck, but the Swiss artists do not pander to such lackluster expectations. There are trees in some...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in