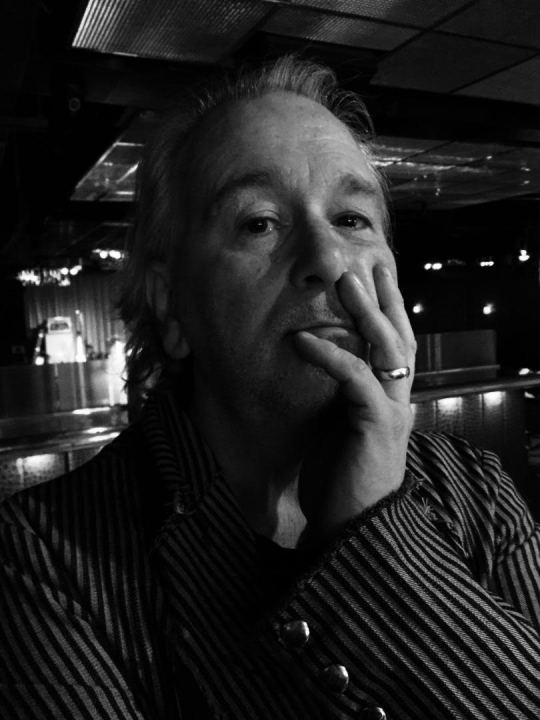

An Interview with Writer Tony Burgess

Tony Burgess is best known for the horror novel Pontypool Changes Everything, about a zombie virus that is spread through language. The book served as the basis for Bruce McDonald’s film Pontypool, which Burgess also wrote. In a genre often considered formulaic and staid, Burgess is strange and extreme; his recent novel, The n-Body Problem, contains a chapter that is unreadable because mathematically encrypted. The books read as if written by, to quote Burgess, “a deteriorating consciousness.” They are things that should not be, novels that disconnect themselves from the conventions of both horror and literature.

—Jonathan Ball

I. “I AM INTERESTED IN GIVING THE READER TRUE VERTIGO.”

THE BELIEVER: Your books, from the beginning, have embraced horror—a much-maligned literary genre—while at the same time having few similarities with other horror novels. Your influences are almost untraceable. I can detect Burroughs, I think, and Cronenberg, but maybe a good place to begin is where you began. How did you come to horror, and to cultivate your own particular strain of experimental, literary horror?

TONY BURGESS: It’s natural, isn’t it, to assume influence is primarily literary? And along the way it has to be, but my experiment began with, and still includes, non-literary influences.

I’ll be plain about this—I sought out horror at a very young age because I understood it. More than that, though, it was occurring. I have been frightened for as long as I can recall. I am shocked by this and feel isolated. That we aren’t holding onto things, like trees and rocks and screaming, surprises me. That was sort of the environment in my head as a child—that there is mindless violence in everything, and anything quiet and welcoming is so because it knows you by name, and that name marks you for sadism. Everything we think is real is made of elegiac materials.

So that was my backdrop as a kid. I couldn’t articulate it but I sought out things that could. At first it was horror films—extreme panic and terror, grotesque and maniacal. These films calmed me and made me feel more connected in my experiences.

As I got older my psychic life grew dire and started to resemble paranoid schizophrenia: disordered thought, a terror of secret, malevolent designs, an overwhelming sensation of being deformed. I had to seek out stronger medicine, and so I started obsessively reading surrealist and Dadaist texts.

That was when I started to have a tiny bit of control. Jarry, Beckett, Artaud, Bataille, Lautréamont, Genet, Gide, Cocteau, Apollinaire, the inframince of Duchamp. Then from there, outward to devour anything I...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in