An Interview with Ottessa Moshfegh

I first read Ottessa Moshfegh’s fiction in NOON. After that, I found her other stories in The Paris Review, where she was awarded the Plimpton Prize in 2013. In 2014, Rivka Galchen selected her novella, McGlue, as the winner of the Fence Modern Prize in Prose. McGlue was shortlisted for The Believer Book Award. Moshfegh has won a Pushcart Prize, an NEA award, and was a Stegner Fellow at Stanford. Her current novel, Eileen, is just out from Penguin Press and deals with a young woman in 1964 New England who finds herself befriended by a woman who lures her into a dark and harrowing crime. We chatted recently about Eileen and other things.

—Brandon Hobson

BRANDON HOBSON: One of the things that fascinated me about Eileen is that she seems unsure of her sense of affection. Early in the book she tells us that she bit a boy’s throat and didn’t care that it drew blood—a fantastic description and confession, by the way—yet she seems shy and unsure about admitting her attraction to Rebecca.

OM: Yes. She bit a boy’s throat because he was trying to get his hand up her skirt. Her affection for Rebecca is complicated.

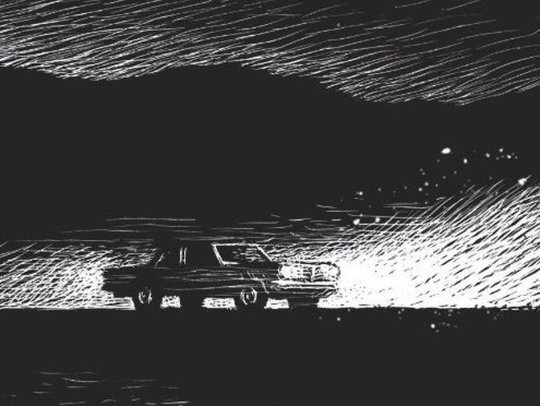

BH: Their complicated relationship is what really drives the book for me. The situation with Eileen’s alcoholic and abusive father is sad. At one point, she says she sees herself driving off a cliff. Did you want her to be emotionally immature or suicidal?

OM: She’s not suicidal. I think that’s her saving grace—her desire to live. As for being emotionally immature, she is only twenty-four years old. She’s had to cope with a lot of trauma in her life. In some ways, she’s weathered. In others, she’s experiencing some arrested development; she never learned to take care of herself.

BH: I’m fascinated with how her character copes with this trauma. In this way the book is disturbing on a level that reminds me why I love good art: it arouses, makes one uncomfortable. Is that what you try to do with your writing?

OM: I love art because I feel that it’s evidence of the great shared universal power. Some of us can access it in ways that are easier to express. I like art that feels real, that cuts the bullshit. So I didn’t want to write a book that pretended that everything was fine. Eileen’s story isn’t some reductive nonsense about how she had a crush on a boy, and then realized that she had to learn to love herself, or something. I really wanted...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in