Trisha Low Talks to Ben Fama

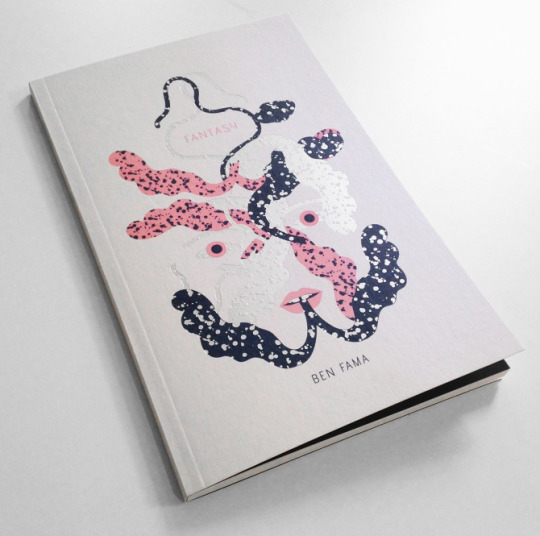

When I received Ben Fama’s book Fantasy in the mail, it wasn’t like getting anything in the mail, because the mail is usually boring and involves bills or those glossy food menus that are always the wrong shade of green. It was Monday, and I was in a very bad mood. Life was confusing, Mercury was in retrograde and everything was very sore and heavy and I hadn’t washed my hair in at least ten days. But that Monday turned out okay because I read Fantasy in the bath, drinking an iced coffee, just like Ben told me Tom Ford does. I found myself swept into an undercurrent that was both luxe and sweaty, clammy and glamorous. I drank my iced coffee and felt a matte nail polish sheen descend upon me, the kind one might find painted over sordid details in the background of party polaroids circa 2009, pinned to anyone’s fridge.

It was Monday and I was sad about a lover (aren’t I always?), and I had started to think fantasy might actually be a giant steel trap designed specifically to fuck with humans in its misleadingly metallic, terrifyingly hopeful sheen. But then, sitting with Fantasy in the bath, I felt love for Ben Fama because without fantasy, the kind that this book knows—an ambivalent fantasy that would take any pastel orange horizon over utopic determinism—I would not have survived twenty-six years on this dumb earth.

—Trisha Low

I. SOMEWHERE BETWEEN AUTHENTICITY AND PERFORMANCE

TRISHA LOW: Fantasy is a collection of poems, but more than anything, it’s a book that creates a kind of diffuse atmosphere or a brittle affect that feels like it enfolds everything you’ve done in it. Do you have stakes in creating an “ambience,” or a “vibe”?

BEN FAMA: I tried to sustain atmosphere and climates over the terrain of these poems. I like how you said brittle. I tried to populate the poems with all of the brittle fictions that may account for psychological weather. But what is the vibe?

TL: See, the thing about a payback interview is that I’m supposed to ask the questions. I think there’s something weirdly claustrophobic about Fantasy, like a closet. It’s very “chill,” comfortable to locate oneself in, familiar and legible but it’s that same languidness that makes it feel as if there’s no escape.

“I wish you could be alive / so I could be your partner / whether in art or life / I’m not really sure / but mostly life I think / but they say life imitates art / so who knows”

The thing...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in