In this series, Noah Charney asks an author to choose a favorite novel that he or she thinks is a hidden gem, deserving of more attention.

Read This: Rabih Alameddine recommends Sepharad by Antonio Muñoz Molina.

Rabih Alameddine is an icon of the San Francisco literary world, and wields not only a pen (or its digital equivalent) but a brush, too. He is an accomplished painter, but is best known for his novels, beginning with Koolaids: the Art of War, The Hakawati, and 2014’s An Unnecessary Woman. Born in 1959 in Jordan, he grew up in Lebanon and Kuwait, moving to England at age seventeen and then to California, where he studied engineering.

Muñoz Molina began his career as a journalist in Madrid, before releasing his first novel in 1986, Beatus ille, about an imaginary city that recurs in his work, which consists of over twenty books to date. He is perhaps best known for Winter in Lisbon, which won numerous prizes and was well-received abroad, and more recently, In the Night of Time, which was translated by Edith Grossman. Muñoz Molina is the director of the Instituto Cervantes in New York.

Sepharad (the Hebrew word for Spain) is a sweeping novel in a scatter of pieces, jumping around in time and place, always focused on the residents of Spain who were unwelcome, cast out, passed over. The novel is not so much picaresque as frog-like, leaping from lily pad to lily pad, stories that may or may not have any link to them beyond a general geography, and with no traditional protagonist or narrative arc. I found it lovely, with some haunting images, but a bit hard to get through, which is why I looked forward to affixing my rudder to Rabih, to guide me through Sepharad’s glittering waters.

NOAH CHARNEY: I’d love to begin asking you why you chose Sepharad.

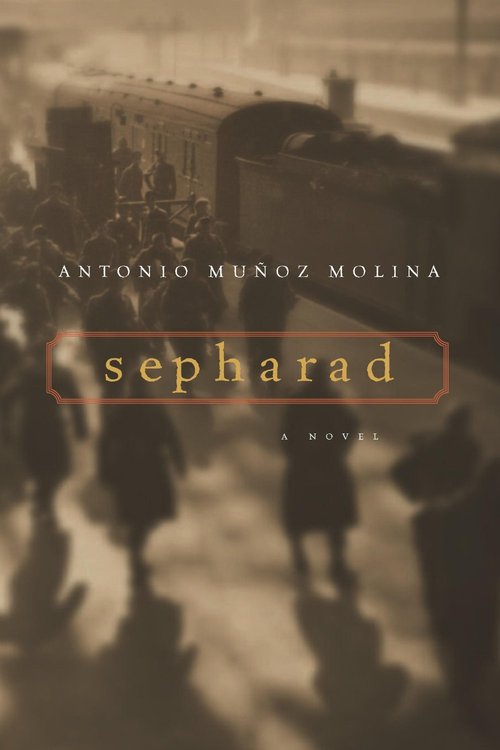

RABIH ALAMEDDINE: Oh, God, um, I can actually remember the first encounter. I found it in a bookstore when it first came out and I was intrigued by the cover and, you know, I started looking, and found it truly astounding. I fell in love with it the first time I read it. And I looked at it again while I was on holiday, because I knew this interview was coming. So this is the fourth time that I’ve read it.

NC: Oh, wow.

RA: And I still get dazzled by it every single time—it’s one of those books. I have a few books I really treasure. Most of the others are...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in