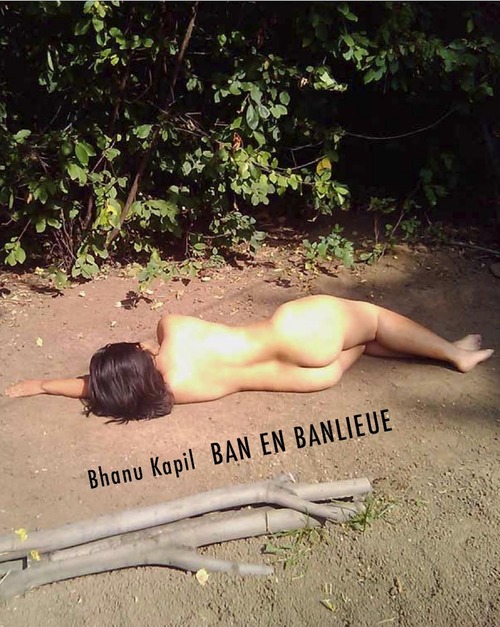

In honor of the publication of Bhanu Kapil’s newest book Ban en Banlieue, just published by Nightboat Books, the writers Amina Cain, Douglas A. Martin, Sofia Samatar, Kate Zambreno, and Jenny Zhang gathered together in a conversation to talk about the work of the British-Punjabi writer, who teaches in the Department of Writing and Poetics at Naropa University. The conversation will be published in three parts.

Day 3: Collectively reading Bhanu Kapil’s Ban en Banlieue

SOFIA SAMATAR: “A girl lies down on the sidewalk.” The repetition of this: Ban killed in a riot, Bhanu lying down at an anti-rape protest in Delhi, and then the woman who leaps into the water during suttee, who lies down there. While I’m reading Ban, the socialist activist Shaimaa al-Sabbagh is shot and killed during a peaceful demonstration in Cairo; two days earlier, Sondos Reda Abu Bakr, a seventeen-year-old student, was killed in a demonstration in Alexandria. Two women on the sidewalk. “It is so excruciating to write about these subjects that I take years, months: to write them.” For me Ban is about women in demonstrations, in public, in politics. “The role of sacrifice, patriarchy, fire-water mixtures,” Bhanu says. And she says: “Write what never ends.”

KATE ZAMBRENO: It feels almost impossible to express the psychic energy in this book, the grief and wit and rage. In it the narrator circles around the story of a woman remembering a race riot in London in the 70s, while tracing, in a visceral way, through notes on performances, blog entries, notebooks, various errata, other bodies deemed as disposable, primarily Nirbhaya, “The Fearless One,” the young woman gang raped and beaten to death on a bus in New Delhi in 2012.

On the first page Bhanu holds a ceremony with Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, and that text is the only one that comes close to me with what Bhanu performs here. Her own Joan of Arcs (like Nibrhaya, like the photograph at the beginning of Blair Peach, the antiracist activist killed by police in a 1979 London demonstration).

JENNY ZHANG: The excruciation of writing about these distortions and mutilations and traumas and displacements creates a safe space where goals don’t really matter, where having a product at the end of production doesn’t really matter. I kind of lost my shit when I saw Missy Elliott sing and dance at the Superbowl for two minutes yesterday. I felt the temporary pleasure of being connected to pop culture. After her performance, her single “Get Ur Freak On” became the most downloaded song in iTunes or something like that. Everyone wanted this to mean she was finally going to release a new album (her last one came out in 2005). It was like the performance wasn’t enough, it didn’t count towards making her a success, someone historic, one of the greats.

So much of Ban is composed and collected of things that don’t count—the acknowledgments page given as much weight if not more than the actual text itself. The actual text itself being the notes around and for and erased from the intended story. The intended story never materializes or becomes important enough to be more than a footnote, or a prologue that appears off stage. Performances that have already happened. So much of Ban is about acknowledging that someone like this can never be considered historic or great. Is creating something that isn’t an obvious success the only way to resist the ugly commodification of succeeding? Is Ban’s laziness the highest form of resistance? Resisting work, yearning to be in the ground, to sink into something, to be lazy, to keep some thoughts so personal that they only exist in the thinker’s mind—is that a protective gesture? Is that what decolonized writing does?

DOUGLAS A. MARTIN: “How does the energy of performance mix with the energy of the memorial?” she is wondering about. A cupped offering. In writing the tension between making a body appear and possibly occluding another. How writing must have its addresses and addressees. The striving is for the sentences to do something in the world, not just blanket what is already there, not just go back over the points that comfort others.

SS: Yes, that’s it, the energy of the memorial, again and again—because the violence extends beyond the context of political demonstrations, of course, into the everyday. Here, too, a girl lies down on a sidewalk. I’m thinking of Jessie Hernandez and Kristiana Coingard, two teenage girls killed by the police while I was reading Ban.

KZ: The past becomes present, through rehearsal, through repetition, like Duras’ Lol Stein, circling around trauma of the past, lying in the rye field (a repetitive image for Bhanu’s work, in Ban en Banlieue, she lies down in performance, as a way to attempt to resurrect grief, a collective and individual past).

AC: In 2011 I saw Bhanu perform Schizophrene [Remix] (for Ban) in a red sack on top of what was meant to be a butcher’s table and she was meant to be a piece of meat. A recording of her reading from Schizophrene played from behind the bushes, loudly, and it was electrifying, certainly a theatre of cruelty, or something related to it. The audience watched from the windows outside, and this added something to the scene, a voyeurism, but also that witnessing, reversed. I watched it again and again (it looped); I couldn’t tear myself from it. How could I feel beauty from a text and performance of such disturbance?

DAM: There is urgency and anger here. “Performance art worked out for me. It helped me to think.” For a long time, in my bookshelf I have had a balled up piece of paper, part of a work by artist Sanja Iveković, where in a protest, like trash over the museum floor lays littered crumpled photocopies, calling for law, drawn from Amnesty International’s literature on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). These are some of the things that we can’t write and the things that we must write. I wonder if writing has to hurt. In Ban, foil gets mashed up.

SS: How to become a writer: throw things.

JZ: Wanting to be a writer, wanting to say something before you’ve ever written anything: “As a child I lay down on the bed like a sentence not written yet.”

AC: When I first read Ban, I felt that it was the story not only of Ban, accompanying Ban, accompanying those who have been struck down, violently, with their lives taken from them, but also of community, a community that might hold the lying down. The book both begins and ends with acknowledgements; in fact, sometimes it is hard to tell where the acknowledgements end and what we might usually think of as “the book” begins. They exist together almost seamlessly; there is really no separation. In her performances of/for Ban, Bhanu takes off her clothes, sometimes she becomes a piece of raw meat, she lies down on the ground in public, she asks “three women of color, who identify as non-white” to stand to her left, “eleven men who are white, or who identify as white” to stand to her right, an invitation “to take, in turns, the chance to hit” (“the white men took in turns to hit me”). These are deadly vulnerable spaces. Is it Bhanu’s community, and deep friendship, that helps to make the lying down possible? Community is so complicated, a writing community definitely so, and I don’t want to reduce it to one thing here, but it’s a question that came up for me.

DAM: Lying down in the whiteness. I am reminded of how complicated a feeling it was for me when I saw Laura Mullen restage “Cut Piece” at a conference on a panel Bhanu was also on, Laura who is thanked in the book (“Root-teacher. Friend.”) Do you take up the scissors or not.

AC: I experienced the book as a kind of cleansing, for Ban and others, to walk right into the space where a striking down has occurred, is occurring, will occur again. The book (and the performances and ceremonies of/for Ban) holds that space. It lies down in it, nakedly, or thrashing as a piece of meat.

SS: I felt that too, that sense of being cleansed, scoured—wrung out! For me it’s connected to what I feel Bhanu is doing with the personal. When she lies down, she’s a person, but also a symbol, and also meat, as you say, like something on a slab, an animal, maybe not even an animal that’s alive in a recognizable way. It’s brutal and terrifying and compassionate and huge. I said in an email to Kate that Bhanu is taking the self out of the selfie! And this connects to her beautiful, generous transparency about her writing process, the way she holds nothing back. She’s so open with the self that it dissolves into people and landscapes and objects.

AC: It’s been hard for me to put it into words, but yes, that totality or continuum of the personal in the lying down (what are the other points along the way?), that dissolving; you say it beautifully, Sofia.

JZ: With that transparency, she’s taking away the myth of genius, the myth of dedication, the myth of spending whole days working on your book and emerging from it, dazed and floating above the world. In Bhanu’s writing, there’s long pauses, stretches of time where nothing happens, moments when the writer must literally stop writing and lie down. “I think about a monster to think about an immigrant, but Ban is neither of these things.” Is this the anti-story of the anti-immigrant? The immigrant who refuses to work twice as hard, the immigrant who refuses to be productive, the immigrant who refuses to prove herself? And so becomes a monster. When I was a child, I knew of certain immigrant families where the heads of the households literally worked themselves to death. Every time I looked into their eyes, I thought, “Stop working,” but they couldn’t and they wouldn’t. Sometimes I found myself angry at the moments of rest in this book. “Keep working!” I thought every time the speaker spoke of lying down. How my reaction exposed me, made me feel naked. Why did I value work? Why did I value greatness? Why did I want a fully embodied text—direct and giving—why was I so resistant to being shown the remaining traces? Why was I so hungry for the thing itself?

AC: This may also be the first book by Bhanu in which I felt her so strongly as an artist as well as a writer, that she became an artist in trying to write Ban (but this isn’t true, of course; she has been an artist all along). This was to be a novel, and instead found its own relation to it. The novel itself was given everything, and the everything became the book. From someone who believes in fiction and in its possibilities, who feels a loyalty to it, I began to wonder, is a novel incapable of holding Ban?

JZ: And all her books, and especially this one, is about how hard it is to put anything into words, and that in contrast with the kind of person who has no problem putting anything into words. “The project fails at every instant and you can make a book out of that and I do, in the same time that it takes other people to write their second novel that is optioned by Knopf and which details the world they grew up in, just as I am—detailing—which is to say: scouring/burnishing the world I grew up in too.”

KZ: What can writing do? What can the book do. What can performance do, the body defiant in public, in protest, in demonstration, that literature fails at? And how can that disappearance and documentation be then traced in a book? How can a book contain somehow the furious energy of its failure, of its processes, its drafts, its many notebooks? How can a book contain and name a community, in all of its fragments and fractures?

SS: “I wanted to write a novel but instead I wrote this.” This is not a novel, it is the desire for a novel. Pure desire. “I wrote these notes not to be included in a book but because of it.” To me that relation you talk about, Amina—the relation of Ban to a novel—it’s endless desire. And that’s part of what makes it so exhilarating to read, vertiginous, consuming. The desire doesn’t end.

DAM: Nor do my notes, or my commitment to this work. “To write a sentence with content more volatile than what contains it.” “To what degree are creative acts antidotes to the desire for cultural or institutional revenge.”

JZ: The idea of cultural or institutional revenge makes me hyper! Bhanu writes in the acknowledgments about how grateful she is for her life coach, “If you are reading this and you also can’t write or complete your book (or project of any kind), contact me and I will put you in touch with her IMMEDIATELY” and that made me hyper too. I want her number. I want this help.

KZ: The play and paratext—the pages of blurbs, of acknowledgements, of notebook selections. Narrative’s urges—the urge towards a novel, towards stories—and then this beautiful, ravaging impossibility. Like a magnificent negative image of a novel—an epic in feeling and scope, a lyric ghosting a multiplicity of I’s.

SS: I love that, Kate: “the negative image of a novel.” Ban is a negative image in the way it performs, reaches out, becoming this impossible thing: not performance poetry, but a performance novel. This happens in Jenny’s example of Bhanu’s offer to put us in touch with her life coach. Or the words: “I transmit this light: to you. Can you feel it? I am sending it right now!!!!” Those four exclamation points—something out of an email to a friend or a comment on someone’s blog—that shoot toward us like rays of light. Yes, Bhanu! We feel it!!!!

Bhanu Kapil’s Bibliography:

The Vertical Integration of Strangers, 2001 (Kelsey Street Press)

Incubation: A Space for Monsters, 2006 (Leon Works)

Humanimal, A Project for Future Children, 2009 (Kelsey Street Press)

Schizophrene, 2011 (Nightboat Books)

Ban en Banlieue, 2015 (Nightboat Books)

Amina Cain is the author, most recently, ofCreature(Dorothy, a publishing project, 2013). Work has appeared in The Paris Review Daily, Two Serious Ladies, n+1, Everyday Genius, and other places, and she is a literature contributing editor at BOMB. She lives in Los Angeles.

Douglas A. Martin is the author of books of both fiction and poetry, including: Once You Go Back (Seven Stories Press), Branwell (Soft Skull Press), and Your Body Figured (Nightboat Books).

Sofia Samatar is the author of the novel A Stranger in Olondria (2013) and the forthcoming The Winged Histories, both from Small Beer Press.

Kate Zambreno is the author most recently ofHeroines(Semiotext(e)) and Green Girl (Harper Perennial). A novel, Switzerland, is forthcoming fromHarper.

Jenny Zhang is a writer, poet, and performer living in New York. She is the author of Dear Jenny, We Are All Find (Octopus) and Hags (Guillotine). She writes for teen girls at Rookie magazine & occasionally tweets @jennybagel.