A Survey of Writers on Contemporary Writers

Listening to writers read and discuss their work at Newtonville Books, the bookstore my wife and I own outside Boston, I began to wonder which living, contemporary writers held the most influence over their work. This survey is not meant to be comprehensive, but is the result of my posing the question to as many writers as I could ask.

MARILYNNE ROBINSON

© Ulf Andersen

JAMES SCOTT: In my MFA program, I remember one teacher had us go around the table and name our favorite authors, and one of the first few people said Marilynne Robinson andthe collective gasp made me scribble her name down and read Housekeeping right away. I’ve re-read itevery year since.

The first fifteen pages or so—the summary of her

grandparents and the train accident—could teach one everything he or she needs

to know about the art of writing. From the perspective to the voice to the

pacing to the vividness of the scenes, it’s as close to a perfect section as I

have ever read. It thematically sets up everything to follow, though that’s not

totally apparent until much later, which it’s why it’s critical that those

pages are memorable: they need to instantly make their mark and become the lore

of the family and the town.

KAREN THOMPSON WALKER: I read

Marilynne Robinson for her wisdom and her eye. Her writing has a way of

reminding me how extraordinary all the ordinary things of this world really

are. As the narrator of Gilead says, “This is an interesting planet. It

deserves all the attention you can give it.”

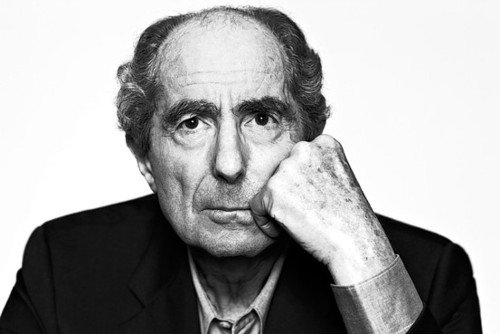

PHILIP ROTH

© Elizabeth Donnelly

T. COOPER: I guess

the world just sort of split a seam when I read my first Roth book, which I’m

pretty sure was Operation Shylock. Though Portnoy’s

Complaint was really the one that cracked the world open and completely

floored me. It wasn’t even that Roth was a conscious influence on my

development either. In an eerie way, I was seeing his influence on my

development in ways I hadn’t even realized until well after it happened. Both

figuratively, and literally—like not even having read a certain book of his

until after I was doing something that somehow came out as a distant relative

of it (for example, Portnoy, Plot Against America).

STUART NADLER: If I were to guess, I’ve read more

of Roth than I have of any other writer, which says something either about my

reading habits, or about how prolific a writer he’s been. I’m writing this two

weeks or so...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in