A Survey of Writers on Contemporary Writers

Listening to writers read and discuss their work atNewtonville Books, the bookstore my wife and I own outside Boston, I began to wonder which living, contemporary writers held the most influence over their work. This survey is not meant to be comprehensive, but is the result of my posing the question to as many writers as I could ask.

JOYCE CAROL OATES

© Nicolas Guerin

DAN CHAON: There are several living writers who have been deeply influential, but I would say that the most important of these is Joyce Carol Oates. I share her interest in extreme psychological states and the grotesque, and I appreciate her concerns with issues of social class in the United States.Her work is formally daring in a way that I admire, and I am particularly drawnto the way her prose can range from an incantatory intensity to a chillydeadpan within the same work. Her work also helped me to find ways to resolvethe tension between the more realistic, “Carver” side of my work and

the more fantastical “Bradbury” side—many of her novels and stories

walk a beautifully delicate line between the “literary” and

“genre” worlds. Books that I am particularly fond of include Haunted:

Tales of the Grotesque; Heat; Black Water; I Lock My Door Upon Myself;

The Rise of Life on Earth; and Wonderland.

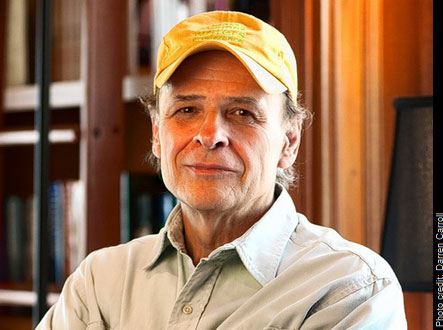

TIM O’BRIEN

© Darren Carroll

BRUCE MACHART: To my way of thinking…and this is wildly subjective,

of course…there are only two perfect books: Anna

Karenina and The Things They Carried. The latter is, all at once, a masterwork of

realism and the only fully successful work of metafiction. The title story is, on its own, a gem, but it

makes me a bit batty to teach that story without the context of the greater

work from which it comes. From the

dedication page (where the book is dedicated to the fictional characters), to

the fictional alter-ego Tim O’Brien who becomes our narrator, to the fine and

ever-developing notions about the difference between historical truth and

“story truth,” the work entices us to believe even as it reminds us that

fiction is made up, that “art” is the root of “artifice,” that the human

condition can be made “more real” to us through the insinuations of the

imagination. This is perhaps the only

book that uses a first-person narrator who teaches us how and why he has the

power to act, at times, as a third-person narrator, complete with the ability

to access the thoughts, feelings, and sensations of other characters. It’s a rare thing...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in