A Survey of Writers on Contemporary Writers

Listening to writers read and discuss their work at Newtonville Books, the bookstore my wife and I own outside Boston, I began to wonder which living, contemporary writers held the most influence over their work. This survey is not meant to be comprehensive, but is the result of my posing the question to as many writers as I could ask.

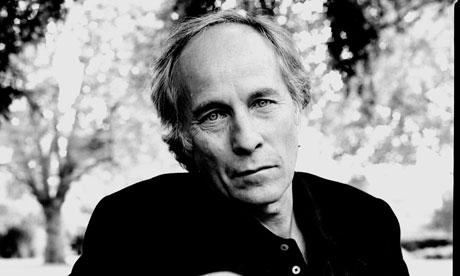

RICHARD FORD

© Eamonn Mccabe

KATHLEEN ALCOTT: I nurture quite a fondness for Richard Ford. He writes the stillness of American life in a way many try to but few actually achieve: he can describe an economically depressed airport bar or stretch of highway so well that the scenes feel like memories being systematically implanted in my brain. Much has been written about the staleness of lyrical realism such as his, but I will defend Ford until I die. Writing like that takes the patience of a saint, and patience is the foundation of any great work. Joy Williams, who occupies another plane entirely, is an inspiration because her work feels like it lives entirely without influence. Emotional truths exist alongside occasional physical absurdities in between extreme discursions—and still she is totally in control.

LAUREN GRODSTEIN: Richard Ford’s Independence Day and The Sportswriter were sitting on my desk, getting read and reread, as I wrote A Friend of the Family. Like Ford’s books, Friend is an intensely first-person exploration of middle-aged malehood. It’s very talky, very ruminative. Whenever I felt at sea with my own novel, I read a few random pages from either of those books and let the voice of Frank Bascombe, Ford’s cranky, regretful narrator, lead me forward.

JOSH WEIL: I’d have to say the greatest influence on me and work at this moment is Richard Ford. That’s because, a few months ago, I read his collection Rock Springs for the first time. And, in each story, I was struck—as I am by the work that moves me most—by an inability to see at first exactly how it works. There’s such a naturalness to the way the events follow each other that they don’t feel planned. There’s an almost uncanny verisimilitude to the way the characters speak; the dialogue feels as real as any I’ve ever read. And, perhaps even more baffling and impressive, the thoughts of the characters feel to me as real as any I could ever know. Baffling because, at the same time, I am always aware of the craft, the skill that’s gone into shaping each of these things. To pull that off—making what’s on the page feel magically alive, almost untouched by an author’s hand, while at the same time crafting each bit of it with such care that each piece is integral to the success of the whole: that’s something not just worth reading, but, as a writer, worth striving for. It’s the goal I’ve set for myself for these stories I’ll work on next. And so, at this moment, Ford is surely the writer whose work is most clearly working on mine.

JONATHAN FRANZEN

© Ulf Andersen

CHRISTOPHER BEHA: I spent the summer before my last year in college taking notes toward the experimental novel I intended to submit as my senior thesis the following spring. I say I was “taking notes toward” it, rather than “writing” it, because it was going to be an intricate puzzle of a novel, the kind that disdains the messiness of the outside world in favor of the self-contained perfection of the Fabergé egg. It probably goes without saying that this novel never got finished but it might be some surprise that it never even got started. There is a very simple explanation for that fact—the week before I went back to school, I read The Corrections.

It was the first work of fiction published in my adulthood that seemed to bring with it an entire literary context, one that became quickly familiar not just to publishing insiders and aspiring writers like myself but to some part of the larger culture. That week in early September when the novel appeared, a profile ran in the New York Times Magazine bearing the headline “Jonathan Franzen’s Big Book.” I was suspicious. I hadn’t heard of Franzen before. Having spent the better part of my college years reading contemporary American fiction, I thought that anyone likely to write a “big book” would be known to me, at least by name. Some part of my thought that the mark of a great writer was precisely that he was known to me before he was known to the average reader of the Times Magazine. But the profile described an appropriately grueling decade spent struggling with this big book. It spoke of a literary apprenticeship at the feet of DeLillo, Gaddis, and Pynchon, and a friendship with David Foster Wallace—these four being precisely the writers with whom I’d spent the previous few years grappling. The profile also quoted from an essay Franzen had written some years before in Harper’s—now my employer but at the time just my favorite magazine, because it published Wallace—that was among other things about the feasibility of the “big social novel” making a real impact in contemporary America. The profile made clear that Franzen had succeeded in writing just such a book.

All of which is to say that The Corrections probably would have mattered to me even if it had not been a great book, simply for the possibilities it suggested to a young writer. But it was a great book. Franzen had indeed succeeded in writing a novel that brought its audience news about the state of the union and the souls inhabiting it, and the audience had shown itself willing to listen. The day after I finished the book, the towers went down. Late in the day, I picked up the book and turned back to the beginning: “The madness of an autumn prairie cold front coming through. You could feel it: something terrible was going to happen.” One very minor result of that day, among all the more serious ones, was a lot of public hand wringing by prominent American fiction writers about whether what they did mattered for anything. If I’d still been working on that experimental egg, I might have had the same question. But a book like The Corrections seemed to matter only the more.

KATHERINE HILL: In 2001, my head was buried in the Western canon, but even I couldn’t miss The Corrections. It stood out importantly in bookstores, those tall white-on-black caps announcing Jonathan Franzen’s name, that elegant title at once reclaiming the American novel and critiquing American society, that severed portrait of the whitebread family at dinner, that headless tie on the spine. I’d read very little current literature at the time, but this, it seemed, was it. So I plunged into “The madness of an autumn prairie cold front coming through;” into the sad anger of the Lampert family’s lives; into the raw, confusing, and entirely unprecedented experience of arguing with a writer in my mind. Franzen’s sentences sprang off the page, torquing irony into earnestness, thought into character, detail into society. And yet, how frustrating his characters were! How selfish, how self-destructive, how mean. I doubted Denise’s affairs, scoffed at Chip’s Lithuanian farce, wanted more from banal Gary than his author seemed to think he deserved. In so many ways, I found Franzen as wrong as Enid finds Alfred. Yet by the last page, I’d completely forgiven him, discovering, quite improbably, that my ignorant first impression was basically, well, correct. This broken family was literature, and if I wanted a part in it, I’d have to be as fearless as Franzen. Really every writer should be as uncensored as he is, as feeling, as intelligent, as ambitious in style and scope. Who will ever conquer the American family, the American temperament, the American mind? No one. They are mountains too large and changing. But we’ll never even glimpse them without writers like Franzen bravely hurling themselves at the rockface.

ANNAPURNA POTLURI: Some years ago, in the crowded isolation of a New York subway car, I was reading a back issue of Harper’s Magazine, immersed in Jonathan Franzen’s infamous essay, “Perchance to Dream,” in which he speaks with sociologist Shirley Brice Heath on the personalities of writers. She found that many writers, as children, were social isolates: children who feel alienated from classmates and family. For these children, “the important dialogue in your life is with the authors of the books you read. Though they aren’t present, they become your community.” Franzen, upon hearing this, comments that “I felt as if she were looking into my soul.” I thought back to my childhood room and the many hours I spent alone in it with stacks of Hardy Boys books, The Phantom Tollbooth and From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler and I too felt suddenly recognized.

Loneliness is a perverse catalyst for writers. It creates a monster that can only thrive by cannibalization, generating a spiritual crash that fuels the creative charge necessary for writing. When reading Franzen’s fiction, we find his characters imbued with a loneliness so true to life we can only imagine that their author is all too familiar with it. Here Franzen’s books rise to the level of great work—his characters are realer than real. I say this with the awareness of the high school ballerina who wants to let Mikhail Baryshnikovknow that he’s “kinda like super talented:” Jonathan Franzen is a great writer.

When discussing literature that is canonical or nearly so, the question is often asked: What is the point of fiction? Aesthetes like me have a problem with the premise of the query, which suggests that art must have some practical purpose. It’s a bit too Protestant. But if I was made to answer, I’d say something like, “fiction teaches us how to be in the world,” or more likely, “fiction shows us how we are in the world,” the disparity between what we profess to desire and what we really want. This is illustrated poignantly in Freedom, as Walter Berglund sits in his car. There is a pretty and willing girl astride his lap, aggressive in her desire for him. Conflicted, Walter—more lonely in this moment than any other—says to her, “I’m sorry…I’m still trying to figure out how to live.“

Franzen isn’t necessarily a beautiful writer; Marguerite Yourcenar he is not. A percussive, Midwestern plain-facedness belies the profound waters in which his work swims: the sentences of The Corrections and Freedom are strung together with a chord of such rank fearlessness that I finished these books feeling fairly walloped in the stomach. The many characters in Franzen’s big, fat Tolstoian narratives display much failing and much ugliness; but, illuminated by Franzen’s incisive eye for the many manifestations of suffering, we connect with them nevertheless. When we arrive, near the end of The Corrections, at “he loved his children,” this otherwise banal sentiment feels like an emotional clobbering.

I am at a point in my writing life when crediting the influence of elder statesmen could be seen less as a compliment than an indictment. And anyhow, Franzen’s prose is American and muscular, where mine is fraught with a South Indian penchant for melodrama, verbosity and languor. I scarcely imagine that Franzen would like to be held responsible for this in a young writer. But he has influenced me. His is the lesson of vulnerability, to write the thing that scares me the most. When, alone at my writing desk, my courage flags, I imagine Franzen, a cartoon angel, saying: Potluri, write the goddamned sentence.

–

Kathleen Alcott is the author of the novel The Dangers of Proximal Alphabets

Lauren Grodstein is the author of the novels The Explanation for Everything, A Friend of the Family, and Reproduction is the Flaw of Love, The Best of Animals

Josh Weil is the author of the novel The Great Glass Sea and the novella collection The New Valley

Christopher Beha is the author of the novels Arts & Entertainments, and What Happened to Sophie Wilder

Katherine Hill is the author of the novel The Violet Hour

Annapurna Potluri is the author of the novel The Grammarian

Lettering by Caleb Misclevitz

–