In Orhan Pamuk’s novel The New Life, a young university student reads a book and, in it, finds a description of a new life that he sets off to find. The novel chronicles the student’s adventures with fellow readers who are similarly impressed by the mysterious book. At the novel’s end, in a distant Anatolian town, the student finds an angel that the book depicted and, in the novel’s depressing finale, he winds up meeting her. (Spoiler: He has to die to see the angel. Death is the price the reader has to pay to achieve the full wisdom offered by the book).

Pamuk’s mysterious novel was mind-blowingly successful in Turkey when it came out in 1994. It sold hundreds of thousand of copies, made its author a star in the literary scene and paved the way for Pamuk’s Nobel Prize in Literature. The New Life seemed to strike a chord among Turkey’s readers, most of whom are pious Muslims, by way of showing the fascinating role a holy text can play in people’s lives.

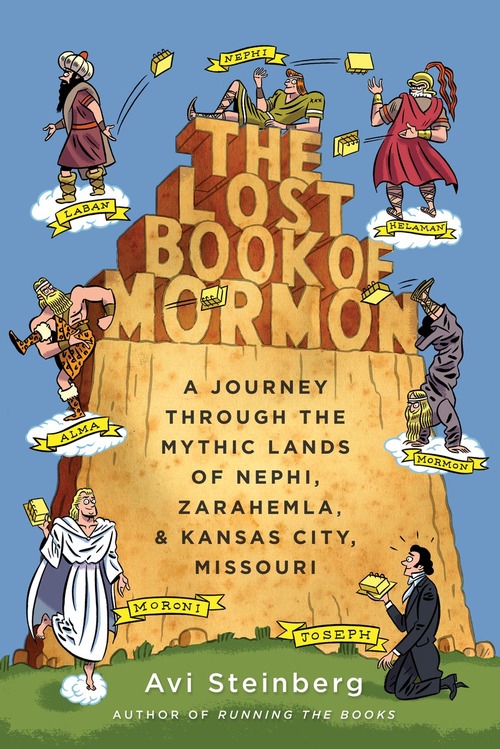

I am not sure if Avi Steinberg, author of the The Lost Book of Mormon, and Running the Books: The Adventures of an Accidental Prison Librarian, read Pamuk’s novel. I have a hunch that if he did, he would enjoy it very, very much. Steinberg, in The Lost Book of Mormon, presents us with a text equally mysterious to the one found by Pamuk’s student: The Book of Mormon; and Steinberg also presents a reader similarly fascinated by it: himself. Happily, he does not die at the end.

“At the heart of my Book of Mormon quest was an effort to understand the difference between prophecy and fabrication, angels and inspiration, delusion and fact,” Steinberg writes in the first chapter. From the start he is aware that being a fan of The Book of Mormon is “to walk a lonesome road” since none of his friends have even read it. “There are many people who don’t realize, or have forgotten, that it is in fact a book, not just a hit musical,” Steinberg observes.

When I Googled “The Book of Mormon” in Turkey last month, all the results—including the Wikipedia article—related to the Broadway and West End stage adaptations which, more than anything else, is a satire of Mormonism rather than an examination of its founding text. Steinberg carefully avoids any discussion of the musical throughout his book, which is difficult. At this point, writing about The Book of Mormon is like writing a book on Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey without once...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in