In this series, Noah Charney asks an author to choose a favorite novel that he or she thinks is a hidden gem, deserving of more attention.

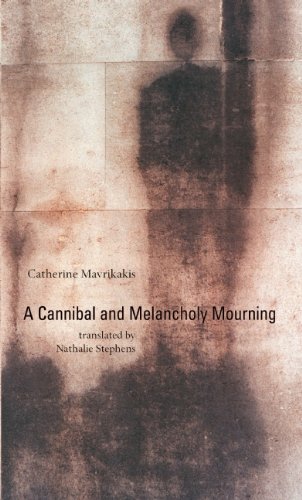

Read This: Kate Zambreno Recommends Catherine Mavrikakis’ A Cannibal and Melancholy Mourning

A Cannibal and Melancholy Mourning is a novel by the French Canadian Catherine Mavrikakis. It tells the story of the deaths of a series of male friends, all of whom are named Hervé. Mavrikakis keeps an emotional distance, so as not to overwhelm the reader with the wave of death that the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and early 90s precipitated. But the book is all the more powerful for the emotional distance and sense of confusion it sows.

Kate Zambreno is the author of the novels O Fallen Angel and Green Girl, and the distinctive piece of non-fiction, Heroines. Book of Mutter, her fourth book, will be published in October 2015. She teaches writing at both Columbia and Sarah Lawrence. Check back next month, when we will speak with Manuel Gonzales about Go Down Moses by William Faulkner.

NOAH CHARNEY: What was your first experience with the book?

KATE ZAMBRENO: I was living in Chicago and starting to help out a bit with Nightboat Books. And I had just met the translator of the text, Nathanaël, who used to publish by the name Nathalie Stephens, an extraordinary French-Canadian prose stylist who Nightboat publishes in the States, whose work deals with translation and going between gender and genre and language. And Nath gave me a copy of the book. I was learning a bit at the time about New Narrative through Nightboat, but at the time I hadn’t read Hervé Guibert, whose novel about Foucault, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, I believe the Mavrikakis text is quite ghosted by. But I was so moved by the energy and atmosphere of it, its rhythms and formal structure as well.

NC: Tell me a little about New Narrative.

KZ: Usually when I think of New Narrative I think of specifically the Bay Area literary scene that began in the late 70s/80s, but extends to a larger movement in American avant-garde literature that coalesced around the AIDS crisis, and deals with writing the explicit and autobiographical body and self, often queer, and writing through theory, and community and gossip, and probably the most famous practitioners are Kathy Acker and Dennis Cooper, but also Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian, and…oh God, no, I’m blanking!

NC: No, no, that’s great. Just to give us a taste.

KZ: …Robert Glück, but also extends into Canada, like Gail Scott’s My Paris, also the works published on Serpent’s Tail, on Semiotext(e), more contemporary prose writers seen as being inspired by New Narrative like Renee Gladman, Pamela Lu. I feel very inspired by it.

NC: Is Mavrikakis’ book exemplary of the movement, or not so much?

KZ: I don’t know if Catherine Mavrikakis would consider herself New Narrative. But the idea that the work deals so heavily with memory and an enraged elegy, this mourning of a series of male friends who died of AIDS, all in Mavrikakis’ text named Hervé. I think the novel is quite poetic, pared down and formally elegant, perhaps that is a departure. More French? Another Coach House work translated from the French I could compare this with is Nicole Brossard’s wonderful Yesterday, at the Hotel Clarendon.

NC: One thing some critics don’t like about the book is that it basically doesn’t have a plot. It’s a series of vignettes in the first person that are somewhat repetitive, and intentionally so. Is that a New Narrative trope, or is that just in this book?

KZ: No, I think that’s more of a tendency of avant-garde literature. If I read New Narrative—or the contemporary lyric essay—as a more current American outpost of the French auto-portrait, like Guibert’s, or Édouard Levé’s, or Marguerite Duras, or what we think of as Écriture Féminine, and wider to the European philosophical literary tradition, the texts tend to be about other things, about a consciousness, about memory, about the self and the body, about language, about philosophy and ideas.

I think in Kathy Acker’s Great Expectations, she says, “A narrative is an emotional moving.” And that’s how I think of the books that I love, I move through them because of tremendous feeling and ideas and language and perhaps suspense is a quality but they are generally pretty plotless.

NC: Do you think it is necessary to know the backstory of Hervé Guibert and Foucault in order to fully understand and grasp this novel? Or if you have no idea about them, can you still enter and enjoy it just as much?

KZ: I think a text needs to work on its own, but with some texts that deal with gossip and community, and other thinkers, a knowledge of referentiality can lead to a deeper—or at least more gossipy—reading. I knew almost nothing about Hervé Guibert when I first read this book, or his autobiographical novel on Foucault and AIDS that I believe inspired Mavrikakis’ text, or Hervé Guibert’s enormous and incredible diary project, Mausoleum of Lovers. I think that’s the thing with New Narrative, too, it’s so much about gossip and community and friendship, and writing about those who died of AIDS. The naming is a political act, the writing is a political act, a revolt against disappearance. I think when I first read it, I was, like, “Why is every character named Hervé?” but loved the playfulness of it. And the narrator is certainly an academic. The references to Heidegger still go over my head. But for me A Cannibal and Melancholy Mourning is this magnificent text of mood, and the author-narrator says that she loves works that are tender and cruel, and that is what this book is for me, a prickly lament, a jeremiad.

NC: Can you imagine a new movement, perhaps related to this one, that would deal with another crisis, another illness, or political crisis, or do you think that was lightning in the bottle of a specific place and time and won’t have parallel in the future?

KZ: I think the question is really, in this rather conservative American publishing climate, does corporate publishing still publish American novels that are radical and political—that are perhaps feral and even excessive, experimental, or quite erudite? Do those works disappear if they are not given this mainstream status or remembered somehow through being archived, being written about, being taught, being reprinted?

Certainly there are novels now in the mainstream that revolve around memory, and autobiography, and are more connected to this philosophical tradition of the novel, but are they political, what do they rage against, do they engage and interrogate history. There is always something to rage and agitate against. The New Narrative was mostly a small-press, underground movement, although writers like David Wojnarowicz and Kathy Acker and Dennis Cooper were given larger platforms. But the Vienna Group of writers, probably my biggest influence, Thomas Bernhard, Elfriede Jelinek, Peter Handke, Ingeborg Bachmann, wrote magnificent novels of national dissent and also reached larger audiences.

In my next novel, I’m reflecting on what is for me a spiritual project of literature, and meditating upon and celebrating writers who I think of as Great Haters. The Mavrikakis directly references Bernhard’s Woodcutters, the narrator sitting in a wing chair, and her academic party stands in for Bernhard’s artistic dinner. Guibert in his novel reads Bernhard as well.

Perhaps in America, for the most part, the urgent work is in the margins, on the small presses. Our urgency as readers, then, our political task, is to make sure these works are remembered, and don’t disappear.

NC: Could it be a clever tactic to put such messages and such cruelty and tenderness in a novel that was intended to be a popular success? Does it go part and parcel with it that it is in a somewhat esoteric style and is perhaps only intended for a limited audience, or can you bottle up the intent and try to package it in something more mainstream?

KZ: Well, Bernhard was a bestselling novelist, and Jelinek won the Nobel Prize. Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello takes on, among other things: feminism, animal cruelty, atrocity. I would consider Bernhard, Jelinek, Coetzee all writers who are formally innovative and political. I think the larger issue for me is with American publishing, how American works are supposed to appeal to a larger audience, and I wonder sometimes whether that appeal is supposed to be diluted, which is never the recipe for works of urgency, considering the reader and the market. I think the role of literature is not to reflect the mainstream but to agitate against it. I think there are still American editors and publishers who take risks on certain books, like David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives, which was published by Knopf, was definitely about the AIDS crisis and in some ways could be a parallel text to A Cannibal and Melancholy Mourning and Guibert’s texts.

There are some writers who do achieve some visibility while writing urgent, important works. Teju Cole’s Open City also reached a large audience and is a deeply philosophical and political work. The question is, why not more? I think the margins and the underground are incredibly important, it’s just about these books being remembered and continued to be read. Perhaps more prickly and interesting writing comes out of Canada—the writers are better funded!

NC: Did this book influence your own writing, and if so, how?

KZ: When I was writing Heroines, which was originally a novel, and for this next work, tentatively titled Switzerland, more than anything I was influenced by the sense of elegy and urgency and the idea that this narrator—this heightened narrator—was both extremely melancholy but angry. The title is perfect, what literature should be. It’s one of those books you read and are amazed by its risk taking. The grief that is so intense, the fury, the melancholy. You read and think, this is a writer who was not listening to any angels. She is just writing this text that needs to be written, saying what needs to be said. Even if the narrator is calling her academic colleagues hypocrites, she’s not playing anything safe. That impulse is inspiring to me—to not to be liked or loved by what I write, but to write in an attempt to find something like truth.

NC: These are complex concepts that I think are difficult to convert into prose when you sit down to write for less experienced writers. I’m curious, how do you go about teaching writing, and you teach at several universities and I’m curious, either what some of your assignments are or how you take these very intellectual ideas about what writing a narrative should be and convert it to something that younger writers can practically apply to sitting down and writing prose themselves.

KZ: I do teach fiction and non-fiction, and usually I’m interested in works that confuse genre, but I’m very new to teaching creative writing, I don’t have an MFA, or a PhD, I tend to approach it just through my own practice. I try to tell student writers to read as much as possible, not only literature but philosophy, theory, and to form obsessions. There’s a big taboo in fiction creative writing workshops against using the self at all, and I think I try to encourage students to write the self, but to connect the self to something larger, which is to be this thinking, seeing, searching, eternally curious person, and that writing can come out of investigating and trying to understand confusion, and doubts, and obsessions.

NC: Can recommend a publisher that you think needs more attention?

KZ: I think Nightboat Books is starting to get really beautiful attention, the Hervé Guibert journals were reviewed in Bookforum by Wayne Koestenbaum. Stephen Motika is the publisher and Kazim Ali [and Jennifer Chapis] is the founder, and they publish poetry and prose, from the margins, relentlessly queer and postcolonial, feral and poetic works that revolve around silence. They rescue orphans of New Narrative, like Bruce Boone’s A Century of Clouds, they’re publishing a New Narrative anthology I believe with Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian as editors. They publish the most recent works of Bhanu Kapil, a British-Punjabi writer who lives in Colorado, who writes these highly original poetic documentary works addressing alienation and the diaspora, that are in a way anti-novels, her Ban has just been published. They’re doing a lot of stuff in translation, like two novels of the Brazilian writer Hilda Hist. They published Fanny Howe’s novel collection Radical Love, Douglas Martin’s Your Body Figured, the poetry of Dawn Lundy Martin and Daniel Borzutzky.