West of Philadelphia and surrounded by rural towns, Lincoln University, the prestigious black college founded by the Quakers in 1854, was engulfed in the tumult of the 1960s. Because it was halfway between New York and Washington, DC, Lincoln attracted many prominent stars of the era. Muhammad Ali, a legend among college students for his refusal to go to Vietnam, was escorted around campus. The leaders of Deacons for Defense and Justice, a black self-defense group started in Alabama, and black arts leaders such as Amiri Baraka visited and talked to students.

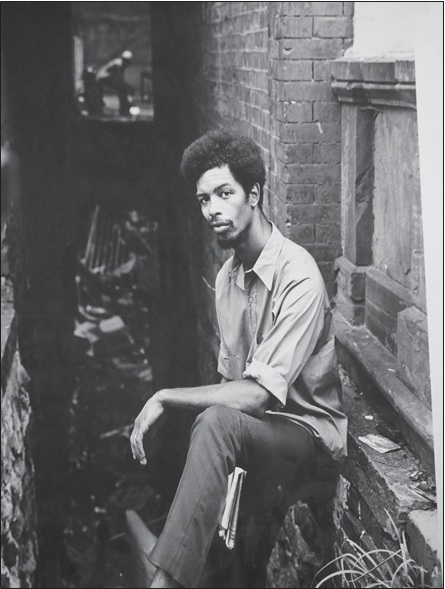

The creative ferment at Lincoln, and the young black students from around the country attracted to that energy, were responsible for the Gil Scott-Heron who moved millions with the messages in his music and helped influence generations of musicians. Most of Gil’s early band members, including collaborator and cowriter Brian Jackson, attended Lincoln, where they found each other, formed groups, and made music. Lincoln was somewhat insulated from the anger and rage exploding on urban campuses, allowing students to absorb the changes convulsing the country without being overwhelmed by them and to respond to it in their own ways.

In September 1969, the school was on the verge of revolt. As a rural school, too far away from urban unrest, Lincoln didn’t experience the explosive rage blowing up on other black campuses such as Howard University or Morgan State. But there was plenty of anger directed at the conservative school administration, which looked down on political demonstrations and some of the free-form creativity taking place on campus. The school had started admitting female students only the year before, and some of the older students and faculty were still resentful at the changes taking place on campus. But Gil and his friends kept pushing for even more change.

Among them was Carl Cornwell, a student who occasionally jammed with the Black and Blues and who had his own band, a jazz quintet that played a lot of contemporary music by Herbie Hancock and McCoy Tyner. Called the Harrison Cornwell Limited after Cornwell and trumpeter Joe Harrison, the group had originally included Brian Jackson, until Gil snatched him away to play with the Black and Blues. Cornwell, whose father taught at Lincoln, grew up in town and was imbued with the school’s pride and heri- tage. But once he became a student, he saw firsthand that the college was lacking essential services and wasn’t responsive enough to the needs of students.

At midnight one Friday in November 1969, at the end of a rehearsal, Cornwell’s group was packing up their instruments when drummer Ron Colbert started having an asthma attack and his inhaler wasn’t helping him...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in