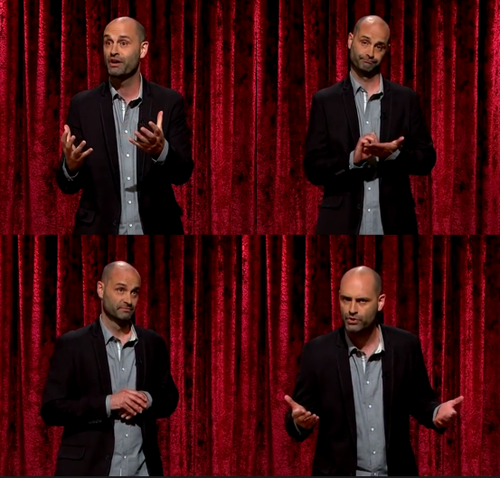

An Interview with Ted Alexandro

New York’s comedy scene can best be described as one big, dysfunctional family. Comedians see each other perform in clubs, they watch each other in bars, at birthdays, and at Bar Mitsvahs. If they are lucky, every once in a while someone in the family gets a chance to perform at Carnegie Hall, as Ted Alexandro did when he toured with Louis C.K.

In many ways Alexandro is a perfect foil for C.K. because his regular-guy stage persona is funny without being potty-mouthed or shocking. His stories are just the opposite—they revel in the pedestrian and the banality of every day life. His comedy is akin to the pitcher on the mound that does a wind up where nobody knows what ball he’s going to throw next.

It is natural then, with so many comedians performing at venues like the Comedy Cellar, Eastville, the Strand, or Upright Citizens Brigade—and countless other venues—that they should collaborate at some point. And some of them do. Following in the footsteps of Louis, Between Two Ferns, Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee and the late Joan Rivers’ In Bed With Joan Rivers, Alexandro has teamed up with his old friend Hollis James to create a comedy web series called Teachers Lounge. Recently they raised $50,000 in a Kickstarter campaign and have continued the tradition of featuring new comedians in every episode.

While many people will recognize names like Janeane Garofalo and Alec Baldwin, fewer will know Dave Attell or Jim Gaffigan, even though they have been in the comedy circuit for decades. Teachers Lounge promises to amuse and delight by bringing together the various members of this dysfunctional family whether they are known, unknown, famous or infamous. With Alexandro being in the middle of all of this, it seemed like a perfect time to hit pause to reflect on where comedy is right now and how his own philosophy informs what he does.

—Chris Cobb

I. SOMETIMES IT’S FUN TO EXPLORE IDEAS THAT MAKE PEOPLE UNCOMFORTABLE

THE BELIEVER: Have you ever stood with a mirror to practice delivery and expressions and that sort of thing, or do you just have trusted friends you ask to see if something works?

TED ALEXANDRO: No, I don’t do the mirror thing; maybe once or twice when I first started out. But after twenty plus years of performing hundreds of shows a year, I prefer to try things out on stage rather than for friends. I don’t see the benefit in that, really. A crowd is the only way to know if something works. Telling a friend or two doesn’t matter. A crowd is what tells you what works or doesn’t,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in