When I first moved to Los Angeles, I sat by Echo Park Lake and read Joan Didion’s 1970 novel Play It as It Lays twice. You have to be a special kind of depressive to read this book more than once, especially more than once back to back. It follows Maria Wyeth, actress and model of minimal success and wife to an up-and-coming movie director, as her life falls apart. Her young daughter, Kate, suffers from a mysterious mental illness and is institutionalized. Maria files for divorce. She gets an abortion. She becomes, in her agent’s words, “a slightly suicidal situation.”

Although Play It as It Lays has achieved classic status—it was on Time’s List of the 100 Best Novels—many readers find Maria unbearably dramatic, self-centered, messy, and babyish. I think it takes a personality with both a tendency towards old-fashioned melodrama and a ruthless, sad/beautiful, cinematic nihilism to pick up what Play It as It Lays is putting down.

I sat on a crumbling stone bench set into the greenery surrounding the lake, and dead birds of paradise got tangled in my hair. It was lovely: ducks hung out in the shallows and the statue of Lady of the Lake laid her shadow in the water. But as I observed the men pushing ice cream carts, the families, dogs, and joggers circle the lake, it was as if every vision concealed a dark edge, a poison that floated imperceptibly in the daylight. Toddlers almost pitched themselves into the water when their parents looked away. A man threw a tennis ball into the lake and his little dog swam out to retrieve it over and over again. Every time it looked to me like the dog was faltering, she had gotten too tired, she might drown right there near the fountain.

At one point in Play It as It Lays Maria takes in the action in the town square of a small beach community. She watches “some boys in ragged Levi jackets and dark goggles… passing a joint with furtive daring;” “an old man [who] coughed soundlessly, spit phlegm that seemed to hang in the heavy air;” “a woman in a nurse’s uniform [wheeling] a bundled neuter figure silently past the hedges of dead camellias.” Maria fantasizes about calling her lover Les Goodwin, and in making contact, undoing her dread. “Maybe she would hear his voice and the silence would break,” Didion writes, “the woman in the nurse’s uniform would speak to her charge and the boys would get on their Harleys and roar off.”

The discrete images Maria observes carry ominous weight because of her loneliness. Her anxiety is evidence of the secret patterns, connections, and implications that a mind accrues when it only talks to itself. “Her mind was a blank tape,” Didion writes of Maria, “imprinted daily with snatches of things overheard, fragments of dealers’ patter, the beginnings of jokes and odd lines of song lyrics.” Her life becomes inseparable from her dreams: images and figures and words and sounds collected, recombined, and imbued with sinister meaning.

Throughout Play It as It Lays, Maria dreams of her dead mother, a shadowy “syndicate” hiding bodies in the plumbing of her house, fetuses floating in the East River, and children filing into a gas chamber. Waking and dreaming, she is preoccupied with rattlesnakes, and her pregnancy and the aftermath of her abortion are dark and strange as a nightmare. Shortly after I moved into my new apartment in Los Angeles, I opened my laptop in the morning and tiny grease ants started crawling out of the cracks in the keyboard. Sometimes dream symbolism collides with waking life by coincidence, but sometimes it is a bad sign.

Didion’s experimentation with dream structure in Play It as It Lays may have something to do with her suspicion of the unity, linearity, and cause and effect of traditional narrative. Didion is one of the essential essayists of the twentieth century, and all great nonfiction writers examine how the consistency we expect from storytelling is incompatible with the contradictions and competing truths of real life. I think of Janet Malcolm, the only contemporary nonfiction writer who rivals Didion for pure intelligence and readability. Over her eleven books, Malcolm has considered the way narrative is created in psychology, journalism, and biography—the artificial order each lays over real life. Malcolm writes in The Journalist and the Murderer:

As every work of fiction draws on life, so every work of nonfiction draws on art. As the novelist must curb his imagination in order to keep his text grounded in the common experience of man (dreams exemplify the uncurbed imagination—thus their uninterestingness to everyone but their author), so the journalist must temper his literal-mindedness with the narrative devices of imaginative literature.

In this way, Didion walks a careful line in Play It as It Lays. She can’t avoid all the traditional conventions of the novel form, and she can’t ignore the mandates of fact. But she must find a way to shape a novel that reflects that archipelago of an industry that is “entertainment,” and Los Angeles, a city whose unifying characteristic is its disjointedness.

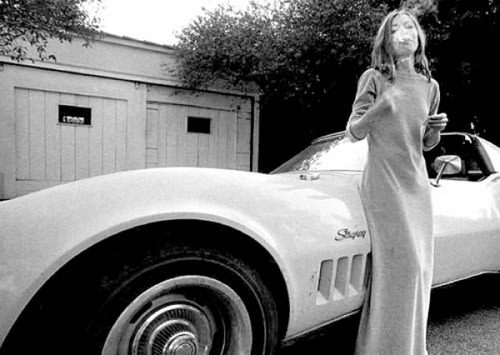

Play It as It Lays begins with Maria compulsively and aimlessly driving L.A.’s freeway system. “She drove it as a riverman runs a river,” Didion writes, and when Maria is not driving, she fantasizes about it:

Again and again she returned to an intricate stretch just south of the interchange where successful passage from the Hollywood onto the Harbor required a diagonal move across four lanes of traffic. On the afternoon she finally did it without once braking or once losing the beat on the radio she was exhilarated, and that night slept dreamlessly.

This practice indicates Maria’s absolute idleness—her husband and daughter have both been taken away from her, so she has nothing to occupy her time or her thoughts. But she is also seeking emptiness. Driving is a meditative activity, the mind and the body working in unison, moving in response to stimuli—the road, the lane, the signs and signals, the other drivers—without conscious thought: the flow of the fugitive act. “Sometimes at night the dread would overtake her,” Didion writes, “bathe her in sweat, flood her mind with sharp flash images… but she never thought about that on the freeway.”

Freeway driving, navigating the network of loops and interchanges that take you right back where you started from, is uniquely appropriate for Maria’s erratic, desperate kind of heroine. With the archetypal Woman on the Edge, whatever she is fleeing from will always eventually overtake her. If “the open road” is an American totem of independence and escape, what does it mean when the road is actually a closed circuit? In Vanessa Grigoriadis’ infamous 2008 Rolling Stone profile of Britney Spears, “The Tragedy of Britney Spears,” she writes about the routine Spears made of paparazzi chases: “She races around [Los Angeles] for two or three hours a day, aimlessly leading paps to various locations where she could interact with them just a little bit and then jump back into her car.”

Spears is Maria in another milieu. Grigoriadis surveys Spears’ struggles from 2003 to 2008, “the most public downfall of any star in history,” as she descended from America’s golden pop star through quickie marriages, rehab stays, her children being legally removed from her custody, and one very public head shaving incident to rock bottom. Grigoriadis describes her as “an inbred swamp thing who chain-smokes, doesn’t do her nails, tells reporters to ‘eat it, snort it, lick it, fuck it’ and screams at people who want pictures for their little sisters.” “The Tragedy of Britney Spears” is pure exploitive Hollywood Camp, a lurid and gossipy rundown of sad events that were already public property. And this sort of pulp journalism is where we are used to encountering characters like Maria, rather than meditations on existential nothingness like Play It as It Lays.

Grigoriadis admits, “it may be true that Britney suffers from the adult onset of a genetic mental disorder… or that she is a ‘habitual, frequent and continuous’ drug user,” but she does not deem these explanations of the Britney Spears “tragedy” worthy of exploration—they would hazard too much empathy, rendering Spears a human to connect with, rather than a spectacle to gawk at. But as Grigoriadis describes Spears’ unpredictable driving—“a Britney chase is more fun than a roller coaster”—one is struck by the bizarre sadness of the situation, a young woman fleeing an army of mysterious men for hours every day, driving away just to find herself driving back, always being caught, rooted out: it’s like a bad dream.

Didion stresses in her nonfiction how much driving can encapsulate both the dream and the nightmare of Los Angeles. In her 1976 essay “Bureaucrats,” she calls driving the “the only secular communion Los Angeles has,” requiring “total surrender, a concentration so intense as to seem a kind of narcosis, a rapture-of-the freeway.” In 1989 she wrote in “Pacific Distances” how these hours spent in one’s car effect “a kind of seductive unconnectedness” in which “context clues are missing. In Culver City as in Echo Park as in East Los Angeles, there are the same pastel bungalows. There are the same leggy poinsettia and the same trees of pink and yellow hibiscus.” This narcotic streamlining of experience is “one reason the place exhilarates some people, and floods others with an amorphous unease.”

And this is all by design. Didion explores in her 1990 essay “Times Mirror Square” how Harrison Gray Otis, the first successful publisher of The Los Angeles Times, and his heirs in the Chandler family shaped the destiny of Los Angeles. She writes how “Los Angeles had been the most idealized of American cities, and the least accidental,” as the Chandlers heralded the gospel of unlimited development: “This would be a new kind of city, one that would seem to have no finite limits, a literal cloud on the land.” This is why certain attributes that seem accidental, “the sprawl of the city, the apparent absence of a cohesive center,” are in fact imperative to Los Angeles’ raison d’être—and are why driving is, as Didion writes in “Pacific Distances”, “for many people who live in Los Angeles, the dead center of being there.”

The idealism of this “cloud on the land” stands in ironic juxtaposition to many facts about Los Angeles—including the constant threat from the many natural disruptions the city is vulnerable to. Didion has written at length about wildfires, landslides, the Santa Ana winds, and earthquakes. In Los Angeles, dealing with this danger and disorder often means not dealing with it, adopting, as Didion describes in her 1988 essay “Los Angeles Days”, a kind of “protective detachment, the useful adjustment commonly made in circumstances so unthinkable that psychic survival precludes preparation.” It is, as she wrote twenty years earlier in “Los Angeles Notebook,” “the weather of catastrophe, of apocalypse… [accentuating Los Angeles’] impermanence, its unreliability.” This impermanence is the city’s true meaning, the shifting center of being there.

Its apocalyptic weather is not completely opposed to the Los Angeles dream of endless sprawl—in the idealists’ eyes, the Los Angeles of today or yesterday is impermanent, indeterminate, and ultimately unimportant. It can always be torn down, rebuilt, and reimagined. Disaster and development have a similar relationship to that of “The Tragedy of Britney Spears” and Play It as It Lays, of film language and dream language.

When I first moved to Los Angeles, and when I could pick up my neighbors’ internet signal, I obsessively watched the true crime documentary series Dateline NBC on YouTube, particularly those episodes hosted by Keith Morrison, a rakish, ghoulish Canadian journalist with a luxurious mane of white hair, who seems to take macabre, theatrical pleasure in the stories of people killing their spouses for insurance money, killing their lovers’ spouses, pushing their business partners off of boats, or bludgeoning strangers while on meth benders.

Many episodes of Dateline take place in Los Angeles’ outlying areas, suburbs and small towns in Orange County or San Bernardino County or the Antelope Valley, places where residents think they are sheltered, just beyond the reach of urban chaos. These are mostly towns that were developed in the mid-twentieth century, part of that tract-house-studded sunbelt that saw a huge growth in population with the Cold War aerospace boom. People migrated for the chance to reinvent themselves as members of the all-American middle class in shiny Southern California, a chance to lead lives like the families they saw on television. And for some, that dream was realized: for many of the interviewees on Dateline, it seems like they can’t believe their lives have become TV-worthy, like the murder of their family members is the only interesting thing that has ever happened to them.

The Dateline mysteries about these boom suburbs are a peculiar bait-and-switch. These people came to California to become producers, and they became part of the product—and not even the most important part. The victims and their families are given due screen time on Dateline, but it is mostly generic, perfunctory: “She could make a whole room smile,” a family member says about one victim; “He loved being a dad,” we hear about another. The best parts of any Dateline episode are about the murderer and the police’s process of tracking him or her down, because the feelings are more straightforward; there’s nothing to complicate the audience’s basically clinical fascination with violent crime and detective work. “This is the story of a mother,” Morrison might say to introduce a victim, but the story is elsewhere.

Our cultural obsession with murder stories and the criminal justice system is a prime example of the impulse to narrativize a reality that is basically unexplainable. For better or worse, narrative is the tool that the system uses to deliver justice: the defense and the prosecution each present their stories, and the one that makes more sense—in other words, the more satisfying one—becomes the reality. And in cases where the crime is heavily covered by the press, the official stories and the media stories tend to elide.

Didion writes in her 1989 essay “L.A. Noir” about a murder case that generated significant media attention—there were, maybe, “five movies, four books, and ‘countless’ pieces” being produced about the case. The murder was only of interest because of the peripheral involvement of the one-time head of production of Paramount Pictures, Robert Evans, and a movie he was planning to produce, The Cotton Club—the man who was killed was purportedly a possible financial backer for the film. Although the case’s connection to Evans and his movie were dubious, every movie, book, and piece proposed about it involved Evans, so that the shorthand for the case became “Cotton Club.” When Didion asked one of the defense attorneys if she thought Evans would ever be indicted, she answered sardonically, “That’s what it’s called isn’t it? I mean face it. It’s called Cotton Club.”

We see that for both the media covering a case and the district attorney, a murder is a story to be sold—whether to a movie studio, a publishing house, or a jury. For Didion, the Cotton Club case affirms the Hollywood faith “in killings, both literal and fugitive.“

In fact this kind of faith is not unusual in Los Angeles. In a city not only largely conceived as a series of real estate promotions but largely supported by a series of confidence games, a city even then afloat on motion pictures and junk bonds and the B-2 Stealth bomber, the conviction that something can be made of nothing may be one of the few narratives in which everyone participates.

This idea of Los Angeles’ massive communal roll of the dice is essential to Didion’s understanding of the city, that cloud on the land, and especially the entertainment industry. “The place makes everyone a gambler,” she writes in her essay “In Hollywood.” “Its spirit is speedy, obsessive, immaterial.” She describes how “the deal” or “the action,” the way the project is financed and who profits from it, is the true story of any movie, and it’s over before production even begins: “the picture is but the by-product of the action.” She even goes so far as to write off any attempt at film criticism because “a finished picture defies all attempts to analyze what makes it work or not work: the responsibility for its every frame is clouded not only in the accidents and compromises of production but in the clauses of its financing.”

An excellent case study in “the deal” is Stephen Rodrick’s January 2013 New York Times Magazine feature “Here Is What Happens When You Cast Lindsay Lohan in Your Movie.” It chronicles the making of Paul Schrader and Bret Easton Ellis’ micro-budget sex thriller The Canyons, which stars Lindsay Lohan and porn star James Deen. Schrader, writer of the classic films Raging Bull and Taxi Driver, and Bret Easton Ellis, iconic enfant terrible novelist of American Psycho fame, were both dangerously close to washed up and looking to make something of nothing, to regenerate both of their careers with one sensational project.

Just how they intended to do that is the subject of Rodrick’s article. Schrader wanted to “do something on the cheap that didn’t look cheap.” There is extensive speculation about where the money is: “This is the future of filmmaking,” Schrader says at first. “Global financing.” Then his model changes again, as, Rodrick writes, “traditional financing for the films Schrader liked to make was gone forever… his future lay in pictures that would not only play indie theaters but also be available on video-on-demand the same day.” Schrader and his partners design a deal in which The Canyons would be “the most open film ever,” with an interactive social media presence and a “populist” approach to financing, using the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, with “no studio looking over their shoulders offering idiot notes.” They cast Deen and Lohan, an infamously troubled former child star, to gain publicity for the project.

This, the evolving financial deal of The Canyons, is the story of “Here Is What Happens When You Cast Lindsay Lohan in Your Movie,” as much as it pretends to be about the on-set chaos caused by Lohan. Lohan is a set piece, her melodramatics just serving as an object lesson in the difficulties of trying to make a movie in a completely unconventional way. At one point Lohan sees a magazine with Oliver Stone on the cover and rips it up, cursing because he refused to cast her in a movie. It reminds me of a tantrum Grigoriadis describes in which Spears’ credit card is declined. “A wail emerges… guttural, vile, the kind of base animalistic shriek only heard at a family member’s deathbed,” Grigoriadis writes. “’Fuck these bitches,’ screams Britney, each word ringing out between sobs. ‘These idiots can’t do anything right!’”

Or the fights between Maria and her husband Carter in Play It as It Lays. “Fuck it then,” Carter says. “Fuck it and fuck you. I’m up to here with you. I’ve had it.” In her nonfiction, Didion resists the popular narrative of the entertainment industry’s sordidness. “This is a community whose notable excesses include virtually none of the flesh or spirit,” Didion writes in “In Hollywood,” as “there is in Hollywood, as in all cultures in which gambling is the central activity, a lowered sexual energy.” She writes of a subset of “’young’ Hollywood” “on which the average daily narcotic intake is one glass of a three-dollar Mondavi white and two marijuana cigarettes shared by six people.”

But Play It as It Lays seems to send a different message: there is plenty of the juicy degeneracy we expect from pictures of Hollywood excess, like the sex life of Maria and Carter’s friends Helene and B.Z., who indulge in swinging, group sex, S&M, and voyeurism. Like Rodrick’s article, but at a more fundamental level, Play It as It Lays is about “the deal.” And like Rodrick’s article, Play It as It Lays also includes as a counterpoint that which can be traded on, the most animal of human emotions and actions—anger, violence, and sex—inflated to the extent that, when observed, they can cause an excitement and amusement that feels basic, satisfying, that has the quality of fantasy: a story.

If an analogue for Play It as It Lays is to be found in Didion’s nonfiction, it is her classic essay “The White Album,” in which Didion, describing a personal experience of failing mental health in the late sixties, decides that her own associative break might actually have been an appropriate response to societal stimuli. She quotes from her own psychiatric report:

It is as though she feels deeply that all human effort is foredoomed to failure, a conviction which seems to push her further into a dependent, passive withdrawal. In her view she lives in a world of people moved by strange, conflicted, poorly comprehended, and, above all, devious motivations which commit them inevitably to conflict and failure.

In this state of withdrawal, she recalls experiences “devoid of any logic save that of the dreamwork.”

As with Maria’s “blank tape” mind, imprinted with sensory detritus, so Didion writes, “All I knew was what I saw: flash pictures in variable sequence, images with no ‘meaning’ beyond their temporary arrangement, not a movie but a cutting-room experience.” Not a movie, no plot or narrative, just a jumble of strange, conflicted, poorly comprehended, and devious motivations and a collection of images that, when viewed together, say nothing.

Didion was preoccupied during this period with high profile Hollywood murders, especially the murder of the elderly silent film star Ramon Novorro by two young “hustlers” and the killings committed by Charlie Manson and his followers. It seems that murder stories inspire Didion with a special dread: attempting to lay thematic order over dumb chaos and cruelty starkly and distastefully reveals the cheapness of narrative. Didion asks Linda Kasabian, star witness for the prosecution in the Manson trial, about the events that led to her involvement with the Manson Family and their bizarre crime spree that left six people dead: “Everything was to teach me something,” Linda replied. This sort of odd and oddly self-centered conclusion is all that can be created out of so much destruction.

Didion describes a haunting “house blessing” that hung in her mother-in-law’s house; it concluded, “Bless each door that opens wide, to stranger as to kin.” The verse “had on [Didion] the effect of a physical chill” because it seemed like “the kind of ‘ironic’ detail” that appears in murder stories. How ironic, and how at the same time fitting, that a proclamation of goodwill and trust towards outsiders would preside over the violent betrayal of that trust. This is certainly the kind of detail that episodes of Dateline hang on. Didion at the time lived in a decaying mansion in an increasingly dangerous area of Hollywood; it had become what one of Didion’s acquaintances called “a senseless killing neighborhood,” in which they did not bless the door that opened wide.

Didion and her family were only renting the mansion until zoning changes allowed its owners to tear it down and build high-rise apartments. “It was precisely this anticipation,” Didion writes, “of imminent but not exactly immediate destruction that lent the neighborhood its particular character.” This anticipation is the truth of Los Angeles existence writ small, that tenuousness stemming from the city’s unsustainable development and apocalyptic weather. But of course, ultimate destruction is also the only real truth of capital-E Existence.

The other notable locus of raw material for Play It as It Lays in Didion’s nonfiction is her 1965 essay “On Morality,” in which she searches for a useful definition of morality in a motel room in Death Valley. There are specific images that seem to have directly been transplanted from “On Morality” to Play It as It Lays. At the end of the novel, when Maria joins Carter on location in the desert, they live in a motel with an adjoining bar called The Rattler Room. The bar adjoining Didion’s motel in “On Morality” is called The Snake Room.

In “On Morality” Didion describes a recent car accident on the highway between Las Vegas and Death Valley in which a young man was killed and his girlfriend was seriously injured. Didion speaks to the nurse who drove the young woman 185 miles to the nearest doctor, and whose husband kept watch over the young man’s body all night. “You can’t just leave a body on the highway,” the nurse says. “It’s immoral.” Didion respects this definition of morality because its application is precise: “She meant that if a body is left alone for even a few minutes in the desert,” Didion writes, “that coyotes close in and eat the flesh.” In Play It as It Lays, Maria’s mother dies in a car accident in the desert. Maria doesn’t know the exact date of her mother’s death because “the coyotes tore her up before anybody found her.”

The action in Play It as It Lays moves very intentionally from the city to the desert, that cleansed landscape, absent and elemental, scorched and dangerous. Maria grew up in the desert, in a settlement called Silver Wells that her father, a true western prospector, developed to capitalize on the traffic from a highway that was never built. Silver Wells becomes a ghost town; both Maria’s mother and her home are subsumed by the desert.

This helps explain Maria’s infatuation with nothingness. In the beginning of the novel, when she is being analyzed in a psychiatric institution, she writes “NOTHING APPLIES” in response to her doctors’ questions. “What does apply, they ask later,” Maria says, “as if the word ‘nothing’ were ambiguous.” Towards the end of the novel, “nothing” looms with mystical importance. “Tell me what matters,” BZ asks her. “Nothing,” Maria replies. “Tell me what you want,” Carter says to her. “Nothing,” Maria replies.

What the other characters in Play It as It Lays don’t understand is that “nothing” is not an evasion; for Maria, “nothing” is the exact, eternal truth. “I used to ask questions, and I got the answer: nothing,” Maria says. “The answer is ‘nothing.’” This nihilism is opposed to the gambler’s optimism Maria learned from her father, who raised her to believe “that what came in on the next roll would always be better than what went out on the last.” For Maria and her companions, the desert strips life down to its most basic meaning: that is, no meaning. This is why Maria allows BZ to commit suicide, a decision that forms the climax of the novel. He desired nothingness, and he reached out for it. What could be more natural?

But if the answer is nothing, there is more than one imperative to be found in that answer. Optimism and nihilism—and city and desert, and murder and suicide—are more of the entwined opposites supporting Didion’s vision of existence. As movies and dreams are one, as pulp and literature, as development and destruction, so for Maria the idealism of the gambler is the deepest form of cynicism. Maria says that her father taught her to see life as a crap game—“It goes as it lays, don’t do it the hard way,” she would hear him say in her mind.

At the end of the novel, along with “nothing,” these are the truths that speak to her, that “you call it as you see it, and you stay in the action.” Maria doesn’t commit suicide, deciding instead to keep going, empowered by her intimacy with nothingness, treating life like the crap game that it is. We see sharply that the real estate and motion picture deals that have built Los Angeles—the giant casino of the entertainment industry that will trade on every murder and mentally ill child star—has truly made something out of nothing, of a desert city that will be desert again, from ash to ash returning. “I know what ‘nothing’ means, and I keep playing,” Maria says, and it is unclear whether we should read this as devastation or enlightenment.

In either case, Maria has found it necessary to excise the sentimentality from her life, the lies that form the connective tissue between life events, that make our perception like a movie rather than a cutting room experience. “Fuck it, I said to them all, a radical surgeon of my own life,” Maria says. “Never discuss. Cut.” These are the same old stories and received truths that Didion rejects in her motel room in Death Valley, trying to think “in some abstract way about ‘morality,’ a word I distrust more every day, but my mind veers inflexibly toward the particular.”

Particulars like the old people I saw sitting on a piece of cardboard by Echo Park Lake, hugging. Like the dragonfly fumbling to escape the nets covering the lake’s lily pads. Like the married couple on Dateline who named their house “Happy Camp Ranch” before the husband killed the wife. Once I left my cell phone on my bedside table while I sat by the lake all day. I came home to several text messages from my mom saying that my dad had fallen off of his bike and broken a rib. They were keeping him in the hospital overnight to monitor him. I felt a twinge of painful irony—when you are out of reach, that’s when the danger catches up to your family—but in the tank top weather beneath the leaning palm trees, checking out the ducks and pedal boats and lotus blossoms, was this my fault, did I cause it to happen?