Martin Fritz Huber on Evan S. Connell’s Son of the Morning Star

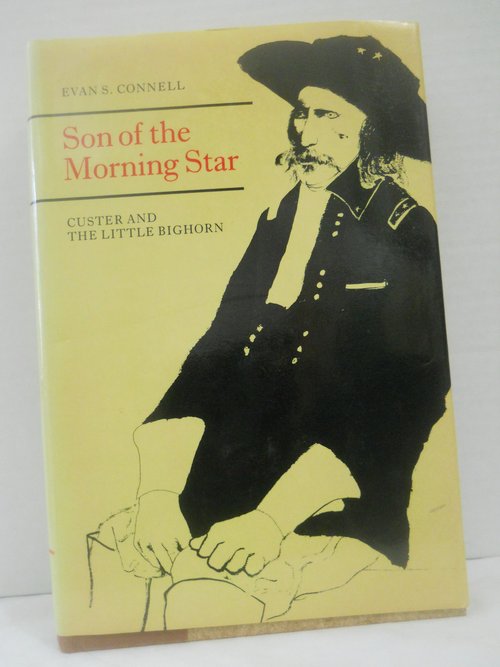

The Spring 2014 issue of The Paris Review includes an interview with the American writer Evan S. Connell, who died in early 2013. This posthumous nod may inspire renewed interest in Connell, whom contemporary readers will know primarily, if at all, for his fictional portraits of a mid-twentieth century Kansas City couple, Mrs. Bridge (1959) and Mr. Bridge (1969). As Mark Oppenheimer wrote in The Believer in February 2005, the Bridge novels are terse sketches of bourgeois repression, each rendered in a series of vignettes where, as Oppenheimer has it, nothing much really happens. Ironically, Connell’s most financially successful title, his ‘Surprise Best Seller,’[1] Son of the Morning Star (1984), was a non-fictional account of General George Armstrong Custer in which a whole lot happens and whose swashbuckling protagonist is about as unrepressed as a latter-day Caligua. In the wake of Connell’s death, Son of the Morning Star hasn’t yet had the revival it deserves, though given the enduring Custer myth, this may only be a matter of time.

Evan S. Connell started out writing fiction. Once he began reading Custer biographies and first-hand accounts from the Battle of the Little Bighorn, he saw that historians would often leave out entertaining, if tangential, aspects of the story, as if to include the peripheral eccentricities of characters would be to undermine a book’s academic value. This, Connell felt, made for painfully banal reading. In his words, “a lot of historians, if they find something funny, don’t put it in. They think it all has to be serious, and their books are so deadly dull.”[2] Atoning for the mistakes of its predecessors, Son of the Morning Star abounds with bizarre marginalia that a more “serious” historian might omit, much of it imparted in the deadpan style typical of Connell’s novels. Take, for instance, the following detail regarding the frenzied alcoholic binges of Captain Frederick Benteen, who commanded a battalion of the 7th Calvary under Custer at the time of the Little Bighorn:

The cause of these drinking bouts seems to be related to his wife, Catherine, who was not very strong and who did not belong on a frontier. He called her Kate or Kittie, logical diminutives. He also called her Pinkie and Goose, names that might be simply affectionate or could have originated during some private moment. However, he very often referred to her as Frabbie, Frabbel, Frabbelina, and at least once as Frabbelina of Gay Street—which is, to say the least, uncommon. (33)

Connell has...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in