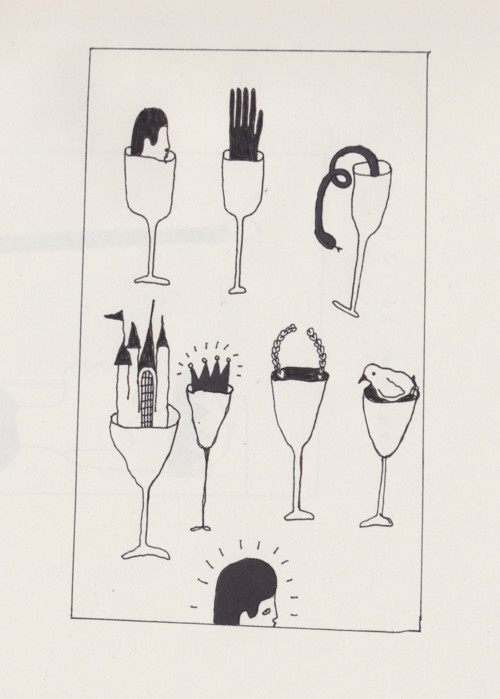

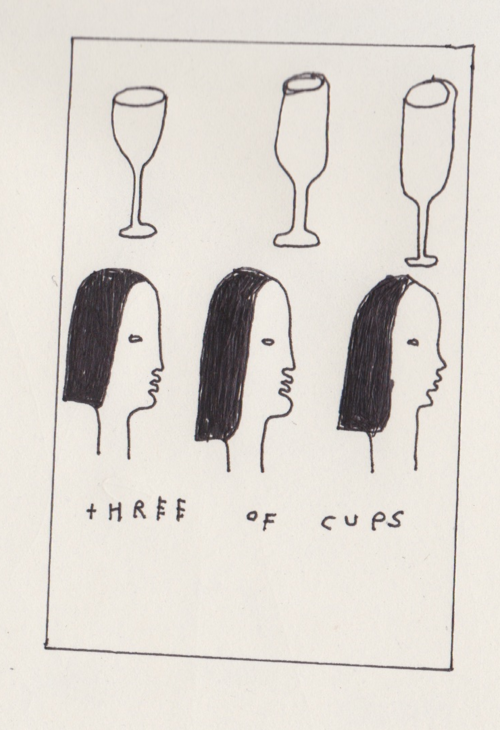

Illustrations by Josephine Demme

In this series five different writers talk to one writer about five (or more) of his different books. In this second interview, Brian Conn talks to Brian Evenson about Immobility. Read the first interview with Colin Winnette, the second with Matt Bell.

Brian Conn in Conversation with Brian Evenson

I was kicked out of a reading room at the Providence Public Library while rereading Brian Evenson’s Immobility. I had been there for several hours when an oily man in a crooked tie approached me. “This room is for students and people with laptops,” he said, looking away. “Not for casual reading.”

Well, the rules are the rules. But as I walked out of the library I wondered whether the oily man’s accusation of “casual reading” was justified. Is Immobility casual reading? I still do not have an answer to this question. Immobility is a science fiction novel featuring scenes of graphic violence, a description that suggests the kind of novel that might be read casually. But it is also a novel about not knowing who or what you are; and that theme is not developed casually, but is instead integrated so thoroughly that by the time you reach the end you are likely to have forgotten forever what you once meant by the word “human.”

That is not among the usual effects of casual reading.

There’s a deadpan humor in some of Evenson’s writing. The scene in Immobility in which one of Horkai’s keepers holds him down while the other prepares the bone saw is a strangely funny scene. It’s a scene that elevates your heart rate and your breathing rate and maybe it just seems funny because you don’t know what else to do with that excitement.

Maybe that’s nervous laughter. After all it is a bone saw. It cannot be serious. It is apparently serious. Evenson offers us no help in understanding whether he is serious or not, whether or not this is a casual book. His language (the substrate of narrative) tells us that we do not know what language is, that language does not know what language is, that we are all blind.

Since so many of the usual categories break down when applied to Evenson’s work, for this interview we had recourse to magic. I spoke to him in his office at Brown University.

—Brian Conn

I. THE THREE OF CUPS

BRIAN CONN: I brought tarot cards. I had this idea that we should use them to talk about Immobility. I don’t know if you spend much time with tarot cards.

BRIAN EVENSON: A little.

...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in