Go Forth is a series curated by Nicolle Elizabeth that offers a look into the publishing industry and contemporary small-press literature. See more of the series.

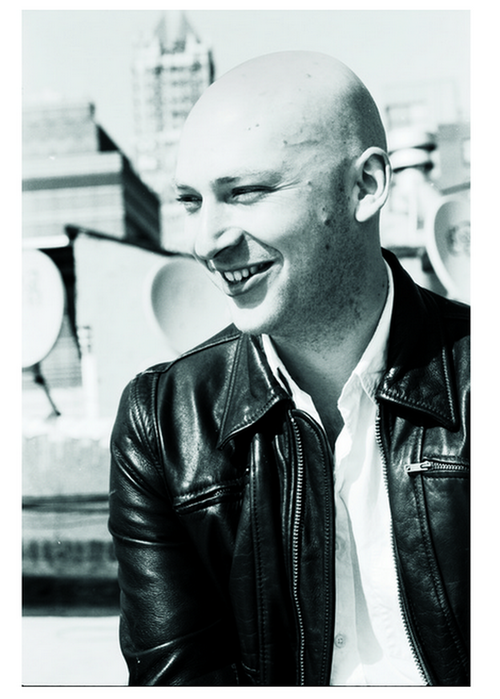

Adam Wilson’s participation in literature ranges from Paris Review columns to teaching gigs to editing gigs and yet he still has an unpretentious vibe about him, which I think is a good example for other aspiring writers. His most recent collection of stories What’s Important Is Feeling is out now from Harper Collins, and it’s awesome.

—Nicolle Elizabeth

NICOLLE ELIZABETH: When did you realize that you were a writer?

ADAM WILSON: I’m not sure if I would have called it “being a writer”, but when I was in high school, I loved telling crazy stories, usually about stuff I’d done over the weekend—drugs, girls, parties. Most of these stories were only loosely based on actual events. I developed a reputation for hyperbole, exaggeration, and flat-out fabrication. But people didn’t seem to care; they liked the stories anyway. I had this moment of realization, like, Whoa, I’m kind of good at making stuff up. I always teach Isaac Babel’s story “My First Fee” to my undergrads on the first day of class. The story is about a teenager who tells such an elaborate wonderful, and completely fabricated story to a prostitute, that she has sex with him for free. He earns her empathy. The “Fee” referred to in the title is the character’s first literary fee, the first time he was paid for a story. In high school, no one had sex with me because I told good stories, but they did start inviting me to more parties.

NE: When did you decide you wanted to write for a living and teach writing as opposed to just writing?

AW: Well, the teaching came later, but I had grand fantasies about making millions of dollars from my writing dating all the way back to high school. At first it was songs. I was in a rock band, and I thought I was the next Bob Dylan. That didn’t pan out. I tried to write a book in college, and assumed I would be paid a large advance for it as soon as I graduated. That didn’t pan out. After college, I wrote a screenplay, and assumed I would sell it, and then retire to a mansion in the Hollywood Hills. Obviously, that one didn’t pan out either. But at some point I figured out that if you did freelance work, and taught, and were a mid-list author, then you could scrape by. That’s where I’m at these days.

NE: How many times have you failed, as a writer, do you think?

AW: Innumerable times. Every day when I sit down to write I fail. It’s the nature of the beast. Writing fiction is a form of communication, an attempt to use language and storytelling to represent ideas, thoughts, and feelings that can’t ultimately be articulated. This is an impossible task, obviously, and all attempts to do it are valiant yet futile. Still, one must keep trying.

NE: What do you tell writers who know they are great writers and feel like they’re failing?

AW: I think that to be a writer you have to have these two sides to your personality. One of those sides feels like it’s failing, always. That side is a ruthless critic. It second-guesses every sentence. That side is cripplingly self-loathing. Every day it must question the value of what you’re doing, and ask the question, does the world really need these characters I’m making up in my head?

The other side must be wildly narcissistic, egomaniacal, and vainglorious. That side must say, YES! This thing I’m doing is the most important thing in the world, every word I type is pure gold, and I deserve to be hailed as the savior of mankind!

If you have the first side, but not the second side, then I don’t know what to tell you, other than 1) you’re never going to finish writing anything, and 2) you’re probably a better person than me, and 3) you should probably see a therapist, because it’s unhealthy to have only self-loathing. But I suspect that if someone asks whether or not she’s failing, she does indeed already know she is great. Some people have both of these sides to their personality, and will turn out just fine. To them I say: patience, my dear.

NE: A lot more than the craft of writing goes into being a writer professionally. What advice do you have for writers who feel like they know they can write, and have absolutely no idea how to approach “any kind of hustle” as it were.

AW: Oh man, I don’t know. Go to an MFA program, I guess? And then meet someone who can read your awesome writing and help the world find out how awesome it is? I think the main thing is to get the work in shape to show people, and then find the right person to show it to. All it takes is one supporter to get a career rolling. That person can be a teacher, a peer, someone from an internship, whatever. So long as you finish the book, and it’s awesome, and you can find someone to fall in love with it who happens to have an agent/publisher/editor etc. who they’re willing to send it to. You don’t have to make everyone fall in love with you, but you do have to make a couple people fall in love with your work.

NE: Do you think it’s important for a great writer to be able to deliver a great reading, a great panel, maybe a great guest lecture or do you think they’re separate and the focus should be entirely on craft or do you think that is, sadly, naive or not at all?

AW: Not important, necessarily, but these things can help. It depends how good of a writer you are. If your book is the next War and Peace, then no one will give a shit if you can’t give a lecture or are awkward during readings. They’ll think it’s part of your genius. If you’re me, though, and your book is published as a paperback original to little fanfare, then it can be pretty useful to give an amazing reading, or panel, or lecture, as it might put you on someone’s radar, and someone who otherwise would never have known about your work might end up getting into it.

NE: This column is for writers who want to learn more about the facets of publishing, do we tell everyone just to write from the heart and go from there and they’ll find their way, or do we tell them that they have to do more to sell themselves and if we say that, are we doing craft a disservice or are we helping it to see more readers?

AW: Honestly, I don’t know the answer to that question, and it’s something I struggle with all the time. It’s funny, I did an interview a few years ago with my friend Garth Hallberg, and I spent the whole interview giving him shit about not being on social media, and saying things like, “How are you ever gonna sell any books without a twitter account?” And Garth was just like, “Dude, I’m gonna send this book out when it’s done and just see what happens. If no one wants it, then maybe I’ll join twitter.” Anyway, Garth recently sent the book out after working on it for years, and he got a huge, amazing book deal, and I looked like an idiot. At the same time, though, Garth is a truly incredible writer. Not everyone can do that. My own work, for example, though I think a lot of literary writers fall into this category, doesn’t seem to have much mass-market commercial appeal. Church Moms in Des Moines aren’t buying my work, and if they did buy it they probably wouldn’t like it. But there is an audience that I think and hope would be into my stuff if they knew of its existence, and things like marketing and social media can help them do that.