A few months after reading Doug Dorst and J.J. Abrams’ S., I came across a line in Ruth Ozeki’s transporting novel, A Tale for the Time Being. A character is describing the handwriting in a stranger’s diary (that we, the audience, also read): “Although the color of the ink occasionally bled from purple to pink to black to blue and back to purple again, the writing itself never faltered…” I immediately thought back to S., its pages covered in the many different hues of Eric and Jen’s scribblings. Dorst and Abrams have spoiled me—now, when I read a diary passage or come across a letter in a text, I always want it to be reproduced in that character’s hand.

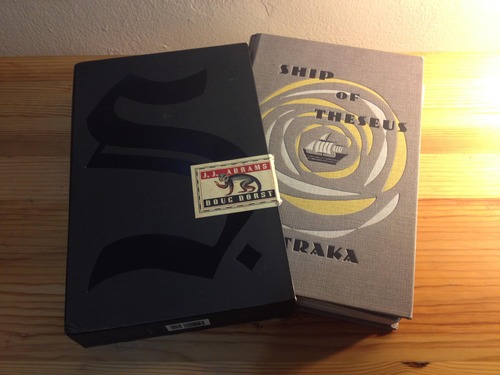

S. is a magnificent work of imaginative packaging. After one rips open the shrink-wrap, a seal still holds the novel within the slipcover. Break open the seal, slip out the book, and you’re presented with a book not called S. but instead titled Ship of Theseus, by one V.M. Straka, bound in an old-fashioned letterpress cover. A dewey decimal sticker on the spine is your first clue that this is a book meant to look as though it was pilfered from the library.

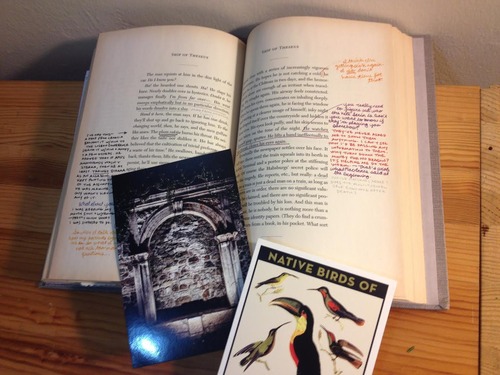

Once you finally open the book, and flip past the blank page stamped “Book for Loan,” you’re presented with the beginning of a written-in-the-margins conversation that flows through the entirety of the book. It’s the first storyline you’ll encounter. Jen and Eric, fellow discoverers of this book, started and continued their correspondence in these pages.

The pages of the book themselves are supposedly the final novel in the oeuvre of a mysterious author, V.M. Straka. They follow a man, the eponymous S., as he wakes up, devoid of any personal memories. He can speak, and walk, and write, but he cannot remember who he is, where he is, or what he was doing.

So that’s two storylines.

The third storyline appears in the translator’s footnotes, for it’s here you learn of V.M. Straka’s other works and life as political provocateur, possible assassin—endless fodder for conversation between Eric and Jen—and also, it’s where the book’s codes are alluded to, and a romance between the author and the translator seems to emerge.

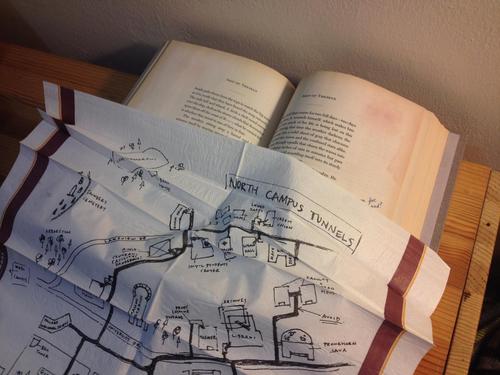

It should be noted here that there are a dozen or more other pieces of ephemera slipped between the pages. Postcards, cafe napkins with sketched maps, handwritten letters, photos, photocopies, newspaper clippings, and a codex are all placed inside the book at opportune moments for them to fall out.

That slipcover makes a lot of sense.

S. is just the most recent in a long line...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in