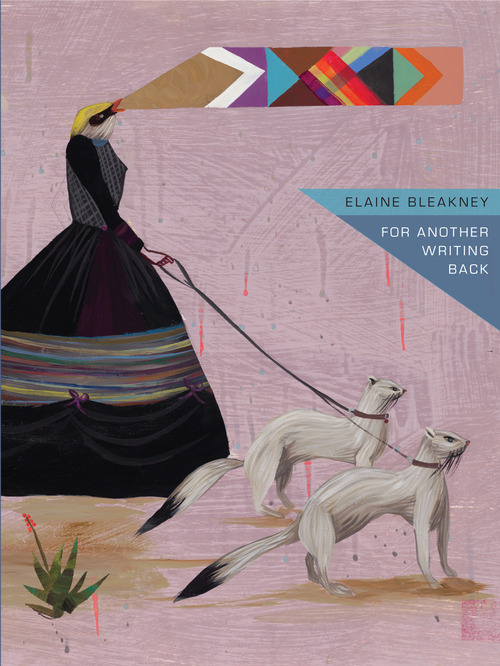

The following is an excerpt from poet Elaine Bleakney’s new book, For Another Writing Back, which will be published this April by Sidebrow Press.

She’s been this body before.

Men-of-war hang. She fans them away with her arms. But the sting—she goes through with her face. They lift her for treatment on the boat, a steroid shot. She slips under again. Three divers surround, watching for sharks. They see pilot whales ahead. The sky on her back. The network says: inspiring. She markets herself with a rhyming phrase and an intention. In her intention to swim the straits, Cuba to Florida, she can’t hear the dead. They sing to her, tired and stung. Where are you going? She can’t ask; she’s not perplexed yet. When she loses feeling—her mind says something should be here, off her spine. The doctor or doctors on the boat warn: one more sting and you’ll be lost. She drops her purpose. She strokes back in.

* * *

My mother’s friend flies down, broken-up. We follow her around the house. She likes to air-dry her body in the morning after a shower or a swim. I have nowhere to put this so I pedal my legs above my parents’ bed.

One night their sound goes wrong: my father’s voice. My mother flickers from her laughter—wait, why aren’t we laughing? She’s a beat behind or ahead. A door closes. Water runs in the kitchen.

I love you unless you lie to me, my father says to us after prayers. My mother smoothes it off the bed. In the Ellwood City High School yearbook my father is shorter than his classmates. In one picture he looks ready to be needed, kneeling by the team. Their mascot is an aching wooden grin.

What happens? My mother’s friend doesn’t visit again. We still have the hollow fish hanging by the pool. Yellow jackets nest in its mouth. My father ducts it up with tape or sprays—straining as we stand at the window watching him on the ladder. I know he’s stung. I can’t see how. I could invent a conversation we had about the fish. Then I would be able to hear them, and locate myself again.

* * *

North to Zipaquirá. Two women in a doorway, one in an apron and the other looking down at yellow in her palm. An older man on a bicycle sparrows by. There’s a...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in