An Interview with Mamoun Eltlib on Sudan’s Cultural Revolution

The late novelist Tayeb Salih, author of Season of Migration to the North, is likely Sudan’s best-known writer. A wide street in Khartoum bears his name. So, too, does a local literary prize. He is a staple in Arabic literature courses at American universities, but according to poet Mamoun Eltlib, Salih has been phased out of reading lists in his own country over concerns that his content is explicit. In fact, there is amnesia of a lot of writers, as Eltlib says most libraries have been shuttered and remaining bookshops barely hang on.

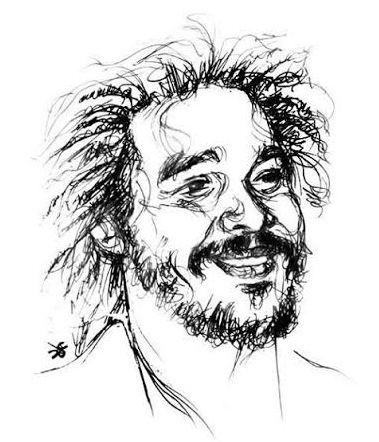

Eltlib should know. The 31-year-old came of age under current President Omar Al-Bashir, whose regime rose to power after a 1989 coup. Though his schools had no libraries, Eltlib became an ardent reader of Arabic titles. He’s a leader in the Sudanese Writers’ Union and recently founded an arts and culture collective called the Work Culture Group, which launched a monthly book market. He’s also involved with a group of writers who founded a new magazine named Taksir, which has some forty-five Sudanese writers contributing from inside and outside the country. By day, he’s an editor at The Citizen, a startup English newspaper in Khartoum. We met at his office last summer, where the lean Eltlib wears a plaid shirt, jeans and sports sandals. His hair twists into long dark locks. Arabic poetry is his main medium, with English being his second language, but he also writes literary criticism and essays. While talking to me about Sudan’s contemporary literary scene, he excuses himself a few times: to send out a press release for the writers’ union; to dislodge a dime-sized wad of Sudanese chewing tobacco from inside his cheek; and to take a short story from the hands of a shy, but bulky middle-aged man who’s just mustering confidence to share his writing.

Despite ongoing strictures on freedom of expression and scant exposure to the arts, there’s a blossoming of creative output among a new generation of Sudanese, Eltlib argues. He provides a rare look at a raw artistic landscape from a country otherwise notorious for news stories around the Darfur conflict, economic sanctions, mass anti-government protests last fall, and the struggles since the 2011 separation of South Sudan as a new nation. Even when talking about serious stuff, Eltlib often lets out a gargling laugh, and occasionally claps his hands.

—Nafeesa Syeed

I. YOU ARE UNDER RISK

THE BELIEVER: What does the Sudanese Writers’ Union do?

MAMOUN ELTLIB: It was established in 1985 by many famous writers and poets; old and classic writers have been president. There have been two revolutions in Sudan, so after the second one, there was a democracy, and they established the writers’ union. The president of Sudan, Sadiq Al-Mahdi, was (and still is) a member of the union. When this government came, after the coup, they shut it down and took his lands and his place. The Islamists shut it down in 1989 and we established it again in 2005 after the peace agreement, because we had more freedom.

The writers’ union usually works in many different fields, such as human rights and the rights freedom of expression through writing. We also publish a yearly magazine.

We started the Campaign for Defending Freedom of Expression, partnering with many different organizations. We do different events through culture and art to make the people aware of their rights.

BLVR: How would you describe the scene now in terms of writing and artistic expression in Sudan?

ME: It’s interesting. In the early stages of this government, in the early 90s, they were fighting everything that could be against how they think about Islam or God or anything. But now it’s different, because now it’s not only political parties. Now there are people outside – independent writers and journalists. So it’s no longer about religion or God or anything like that, it’s just about the power. Anything that might threaten this power, they deal with it very badly. But if you write about anything else, they don’t care.

BLVR: Are people afraid to speak their mind?

ME: We have a constitution, but the regime does not respect it. Through the legal channels, you can get your rights… sometimes.

BLVR: You don’t feel like authorities are going to come and take you away when you criticize the government?

ME: You are under risk. They can come, they can take you, and they can investigate you. It is a little bit different when you get old. For example, when they arrest the students, they often torture and kill them.

BLVR: So there is some fear, but you continue to articulate your views openly?

ME: I don’t feel that I’m afraid. But many people do. The average Sudanese person doesn’t really care. Three days ago, I went to one of the buses in the station, and there were three old men inside. When I entered, the driver was saying loudly to the others, ‘They enslaved us, now we are slaves,’ things like that, ‘We are working like slaves, we are doing everything like slaves, everything is expensive.’ And then the other guy said to him, ‘But what can we do? We make a revolution and then they kill us like they are killing the Syrians and the Egyptians?’ And then the other guy said to him, ‘We did it twice, we are just cowards now. The Sudanese people are cowards and they deserve it.’ And the guy in the front, ‘We have to do something.’ [Laughs loudly].

Finally, the guy in the front said to him, ‘Let’s die! Let’s do it and then just die! We are dying anyway. We are dying in the hospitals, every day we die in the hospitals, do you know anyone who went to any hospital and came back alive?’ [Laughs]. It’s true, it’s really true. Now people are going to hospitals and dying very slowly. Now it’s just unbelievable that people are dying every day. The people are poor and they can’t afford to pay for their treatment. Also, most of the good doctors have left the country.

BLVR: What do you mean when you say most Sudanese don’t care?

ME: They can’t find a leader. They don’t see any. And there are no leaders, actually. These people are negotiating like businessmen – the politicians, the government and the anti-government, the Darfurian rebels or the people in the South Kordofan or the Blue Nile. You can see it becoming a market. Qatar is buying the whole Darfur, and this state is very rich, and they are buying the whole rebel groups, and now they are fighting against each other.

BLVR: So these circumstances don’t make people passionate about expression?

ME: We saw this play in the National Theater called Al-NidhamYurid [The Regime Wants], a spinoff of the Arab Spring slogan, al-sha’abyuridasqatal-nidham [the people want the fall of the regime]. And that’s kind of how the government deals with people—they make them come and laugh, they laugh and they feel, ‘OK these people are saying all of these things about the government, we have the freedom of expression,’ that’s it. You can say anything about the government. Like theAl-NidhamYurid, it’s about this dictator who wants to chain the people because he’s thinking that they are making a revolution against him. The government does allow it, they come and watch. There was a minister there, laughing with the people. It’s not deep, it’s not about thoughts, it’s a very empty play. It’s like they stop your critical thinking.

That’s why we established the Work Culture Group. We want to make deep things, we don’t care about the government, we don’t care about the political parties, they are not our target –our target is the people, spreading knowledge, spreading music and fun and dance. We also have very good lectures every month: scientific lectures, cultural lectures. We bring very professional people for that, like professors from the universities…and the audience is becoming bigger and bigger.

BLVR: But why do you need that? Are you saying that people don’t appreciate the arts and culture they have in front of them?

ME: There is no culture. There is not a strong cultural movement in Sudan. This government has police who fight culture. A whole police unit, called the Nidham Al-‘Aam.

BLVR: What do they police?

ME: Music, art, culture, freedom, individuality. It’s just trying to make the people the same. Carbon copies of each other. They actually managed to do that in the last twenty years, in a way, because the Sudanese people are really changing a lot. The government came to them and said, ‘All of what you did [before] and all of your history is wrong. Now we have to reshape you.’ Their project is called ‘reshaping the Sudanese character.’ And as a friend of mine, Abdullah Muhammad Tayib [a famous painter], was saying to me, ‘It’s like, God was creating the Sudanese in all of his life, since the beginning, he’s creating the Sudanese and trying really hard to reshape them and make them something and then all the way till 1989, and then these people came to him and said God, your work is wrong [laughs], we are doing our own job.’

BLVR: How would you describe the ‘authentic’ or ‘real’ Sudanese culture or Sudanese spirit that they’re trying to reshape?

ME: There is something, it’s just in Khartoum, I think. It’s not something that you can find in other places in Sudan, because it’s really hard to reshape these other communities. They tried, but it’s really hard for them. They are Sufis more than Sunnis, and they believe in sheikhs [spiritual guides] and you can’t just take that out of them. Here in Khartoum, they have the power—and the money—while the rest of the country is becoming very poor, and people who come to the capital are being forced to change.

I can’t describe the Sudanese identity, because it’s really many different identities.

So what makes sense is to describe the character they are trying to build, and how they build it. And now it’s very normal that you can see that the Sudanese people are really into each others’ personal lives, because what the government is trying to do is destroy the personal life. They can get into your personal life and they can force you to do things. They do it through education and they were very successful in that. I’m one of them, because I was very young when the government came, and I went through their whole educational system. I was an actor when I was young, and they came to the schools and took the talented people and then made them do the Islamic songs and the jihadi songs and all of these things. It’s a brainwashing machine. But I don’t think that they managed what they set out to do. All the artists that I was working with when I was young, when I meet them now, they’re still artists.

II.THERE IS SOMETHING CALLED LIFE, YOU KNOW?

BLVR: So, has this period been a step back in Sudanese arts and culture or a time of loss?

ME:Yes. Even in the language.

One of the problems is that they destroyed both languages—English and the Arabic language itself. They Arabized the system, they changed it to Arabic, the universities, the schools, everything. But even with Arabic, when they teach the language, they teach it in a way that makes you start to hate the language itself. Because it’s becoming a very… violent kind of language.

They shut down all the libraries in the universities and in the schools. You can no longer read literature. When we came up, there were no libraries in the schools.

BLVR: Growing up, you never had a library at your school?

ME: Not at all. Before this government, usually you would find people in the buses with their books and with their newspapers, now you can’t see that.

When I read in the bus now, I become like an alien. People start looking at you like this [cranes head over shoulder]. ‘He’s reading. What is he reading?’ They look inside. Someone might ask you, ‘Why are you reading this? Are you in an exam or something? Is there an exam or something?’It’s just disappeared, the whole culture of reading.

BLVR: When did this happen—this disappearance of reading?

ME: In the middle and end of the 90s. The people who read and had a connection with art and literature were kicked out of the whole government system—these are their enemies.

BLVR: How has this affected writing in Arabic?

ME: Writers cannot write well in Arabic [laughs]. Not just the writers, the journalists, too. I was working as a proofreader last month and it’s unbelievable, it’s really unbelievable. Whole articles without any commas, and ten to twelve mistakes in one line. When I first came to work, I found two very old men, sitting on two computers, both with master’s degrees in Arabic language, and they used to be Arabic teachers. They took off a lot of teachers from the schools, people who really know the language. They brought people who are very, very tough guys [laughs] – very tough. It’s really violence, you don’t feel it’s a living language; you just feel it’s like a dead language, a bloody language.

Even the education methods, they changed all of it, they really changed it. When you take the libraries out of the schools, how can you expect people to really love the language, if they don’t find, say, Tayeb Salih as an example?

BLVR: So what does the literary landscape look like now?

ME: Actually, now we have a lot of very creative artists and writers. Over the last six years there has been a kind of revolution in the cultural scene.

These very small groups started to do some things, like the group Shawar’aiya, who have started to put on plays at the Nile Street every week.

BLVR: How did the ‘cultural revolution’ occur if you had so many forces working against art?

ME: It’s a sudden interest. People felt attracted to it more than to the politics. When you come to politicians now, people don’t really care about them, because they find out it’s just a chair or election problem between them. It’s not about them as Sudanese. So when you do something for the people without asking them to vote for you or elect you or to do anything, just to make a very beautiful, attractive program, they respond. I was in Doha for a conference for three days, to solve the problem in Sudan. They brought all the intellectuals and the writers and the thinkers from the political parties and from the rebel groups and from the government itself, as well as independent writers like me and Faisal, and they made this paper called, ‘Loving Your Enemy Through Culture,’ because I was saying that we don’t just need to change the people, we need to change the politicians. If we really want to fight now, we have just one way, the cultural way.

The political language is empty; it’s meaningless for the people now. If you say ‘God,’ it doesn’t have any meaning. If you say, ‘justice,’ it doesn’t have any meaning; if you say, ‘democracy,’ or ‘human rights,’ those terms don’t have any meaning. People lost all of these things, from 1956 until now.

BLVR: So in all of this, what is the role of the Sudanese writer, or the role of the writer, in general?

ME: The role of the writer, as I see it, is to destroy the language that people use in political speech or to describe their ethics and culture. It’s really a fight against the language that’s been fucked up. Like Arabic itself, or the language that people use to say ‘justice’ or all of these things. How can I describe it? It’s destroying the borders between things.

Writers and artists have to make people think open-mindedly. We have to talk about humanity more than talking about the Sudanese or the Darfurians or the Southerners. We have to make them realize that there is something called life and they’ve forgotten it. They’ve really forgotten how to live. You know, if you see someone smiling and happy, it’s very weird; if you laugh loudly or dance freely, people will look at you. I think that the role of writers is just to remind people that there is something called life, you know?

BLVR: I remember listening to Tayeb Salih, who wrote in Arabic, when he was on a panel at the British Library in London years ago. A man in the audience asked whether he considered the Sudanese to be Arab or African. Salih seemed to find it a hackneyed question, not seeing it in quite such a binary, saying essentially, for God’s sake, just look at us, we’re African, and everyone laughed. What do you think about this debate?

ME: Arabic culture is part of the African cultures. The people don’t see it like that because the Arab countries don’t look at themselves as Africans, at all. The Egyptians say ‘the Africans’ and it feels as though they are from another continent or something like that. You have to appreciate the Arabic culture, but people now can’t appreciate it, that’s one of the problems in Sudan.

III. YOU CAN SEE PEOPLE BECOMING MORE BEAUTIFUL

BLVR: Who are the Sudanese writers you’re excited about now?

ME: Actually, I’m very excited. There are two types of writing now, let me say that. Let’s not talk about the bad writing. There are people who got very famous and are now being translated into other languages. For example, this guy wrote a novel called the ‘Darfur Messiah,’ MesihDarfur; when you see ‘Darfur’ on the cover of a book, it will be translated very quickly, you got me? So there are these businessmen writers. They know how to write, their writing is good, but there is definitely a market outside for the Darfur thing or the wars in Sudan that people here don’t know anything about—Sudan is full of really weird worlds.

But there are other writers who I’m really excited about who I think are going to last for a long time. Their work won’t die with the Darfur case. I’m excited about Mohammed Al-Sadig Al-Haj, Mazim Mustafa, Najla Osman Al-Toum, Maysoon Al-Nayoumi, Randa Mahgoub, Naji Al-Badawy, a short story writer, and Ahmed Al-Nashadef, who’s a poet.

BLVR: What about in the Sudanese film and music sectors?

ME: In the film scene, I think Alyaa Sirelkhatim is the best right now. She was doing photography for this movie called Faisal Goes West, it’s an American movie. We have a lot of good film directors now.

There was a disaster in Sudani music. They focus on one type of music and they make Sudanese music, and they stuff it with things that are really from outside, like the violin, [makes screeching sounds] but they’re really bad at it. They were really obsessed with the orchestra, the standard orchestra, the British orchestra, you might say. The Southerners’ music, the South Kodorfan, and the Blue Nile and eastern music and the Nubian music—all different types of Sudanese music get put in this “traditional” category, this idea of folklore. It’s just something you can go and see in the zoo [laugh]. Now people are aware that this is really beautiful. The music that we have is really beautiful and it’s unbelievable.

BLVR: Is there a niche for English publications like your newspaper?

ME: Yes. And there are writers who write in English in their blogs, some who live outside and some, like Maysoon Al-Nayoumi, who live here in the Sudan. They want to write in English and reach the English readers. There are Sudanese English readers, and there are foreigners who live here and don’t know anything about the Sudanese, or they’re just in their cars and huge U.N. buildings and they go to specific places. They don’t know about Sudanese culture or literature.

Some of us are also trying to translate Sudanese literature. I’m working with some translators outside of Sudan like Mustafa Adam, and Ibrahim Jaafar, who lives in London, and they have good translations of Sudanese poetry, short stories, and novels.

BLVR: Is it hard to make a living as an artist in Sudan?

ME: It’s mostly impossible. As a writer, you can’t. You have to work as a journalist, or something like that.

There is a market for painters, but if you want to get into that market you risk losing your individuality. It’s very hard to be unique and commercial at the same time. For example, there is a market for African ladies walking in the desert with this thing over their heads [signals pot over head]. It’s very easy to sell to foreigners. That’s how they see Africa, you know [cracks up laughing].

BLVR: Is there any funding for artists or writers?

ME: Funding? You know Work Culture Group, they are working with zero funding. Everything is from our own pockets. We pay to make culture and art here. Now I’m working here at the newspaper and I’m also funding the events that we do. Like, for the sound system, everyone pays 50 [Sudanese] pounds.

BLVR: Are people thirsty to express themselves?

ME: Yes, very thirsty.

BLVR: Like what do you see on their faces?

ME: Oh my God. You can see people becoming more beautiful. You can see the beauty in their face, you know? Before that, you just feel that they are really ugly, that they are becoming uglier and uglier. But at the events, and the people come together, you can see that there are expressions in their faces [claps hands together].

People are really thirsty to dance. Dancing is a very basic thing, you know. In the last day of [a Work Culture Group event at a] museum—this was really shocking, even for the police—there was this very famous singer, Al-Nour Al-Jailani. His concert on the last day was for free. So the museum was filled with fifteen hundred people, more than three hundred who were drunk and dancing. And alcohol is forbidden. The head of the police was saying to the soldiers, ‘Go and catch these people.’ They said to him, ‘So who do you want us to catch? They are all drunk.’ [Laughs]. You need the whole police force to catch all of these people.

BLVR: At dusk, one night here, the police directed a group of us to leave the banks of the Nile.

ME: Can you imagine? We have two Niles in our city, and we cannot see them. We cannot enjoy them. The Nile! This is nature. It’s not their nature. They are dealing with it as it’s their river.They can do anything with it. They sold the land in the Mugran, when the two rivers meet, they sold it to a fucking Arabic company. Can you imagine that? You are selling your uniqueness. In the whole world, there are no two Niles meeting there [laughs]. The government sold it, the land, you see they are building towers, ugly things.

Nafeesa Syeed is a multimedia journalist based in Washington, D.C. She has reported from across the U.S., South Asia, Middle East and North Africa for major news outlets in the past decade. She is co-author of a forthcoming book on Arab women entrepreneurs from Wharton. Follow her on Twitter @NafeesaSyeed.

Drawing by Emad Abdalla