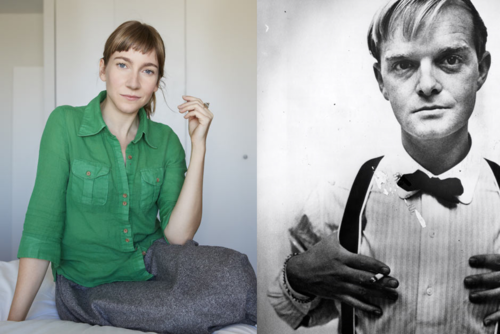

“75 at 75,” a special project from the 92nd Street Y in celebration of the Unterberg Poetry Center’s 75th anniversary, invites contemporary authors to listen to a recording from the Poetry Center’s archive and write a personal response. Here is Sheila Heti on a Truman Capote recording from 1963 and Jonathan Ames on an Arthur Miller recording from 1955. Both Heti and Ames will take part in The Best of McSweeney’s at 92Y this evening.

Sheila Heti on Truman Capote—April 7, 1963

“Just a minute while I stop being vain,” Truman Capote says, and one can hear the click of his glasses unfolding as he puts them on. He has just introduced his story “Among the Paths to Eden”: “Tonight I want to read a story which I have actually never read aloud, and that’s rather a trick because ordinarily … There are certain stories that you can read aloud and certain that you can’t—some that are written for the eye and some that are for the ear. And I really don’t know about this story at all, but I’m going to try.”

Of course, he would have known this story was fine for the ear; he was too serious a performer to make the blunder of reading a story that’s only “for the eye.” Still, one can discern a curiosity about his performance—we can hear him actually listening to himself as he reads. The story is funny and moving—about a woman trying to pick up a recently widowed man in a cemetery. Although the scenario is absurd, it’s also not. It feels like a time capsule—from an era when a woman so desperately had to find a husband or else she might as well live in some cemetery.

When he’s finished, he asks, “Would you like me to read a scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s?” the way a famous singer might ask, “Do you want to hear that single that I know you’ve all come to hear?”—equally chuffed and resigned. The applause is not as enthusiastic as one might expect, and sensitive to this—Capote was likely sensitive to every room he was in—he offers, “Either that or a story.” But no one applauds at that line so we hear him turning the pages to finds the part.

This reading took place in April 1963, upon publication of The Selected Writings of Truman Capote. His friend, John Malcolm Brinnin, a poet and literary critic and former director of the Poetry Center, introduces him, marvelling, “In the very curious sociology of these times, the name of Truman Capote has become a household word, his comings and goings treated [like those of] movie personalities and baseball players. So that...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in