I first encountered Matt Kish’s art in Powell’s City of Books in Portland, Oregon, where a display featured his then-newly-released book, Moby-Dick in Pictures. Being an avid Moby-Dick fan, I purchased the hardback immediately. More recently, when I worked as an editorial intern for Tin House Books, I learned that he was illustrating another book for them, with the same principle behind it—an image corresponding to every single page of the original work. That book is Heart of Darkness, just released this month. Being a student of book publishing, I became intrigued by this unusual approach to the illustration of classics, and knew I had to investigate further. What follows is our telephone discussion in March, 2013 about the artist’s process, how it differed from book to book, and what it takes to complete a project of this magnitude.

—Kylie Byrd

THE BELIEVER: Not to fan-girl out or anything, but Moby-Dick is my favorite novel, so I definitely own a copy of Moby-Dick in Pictures, and I really like your artistic sensibilities.

MATT KISH: It’s really strange how it all happened, I never intended for it to be a book in the first place. I started doing it just for myself and I put it online, on that blog, mostly so my friends and family—who were out of state—could see it.

BLVR: So, did you approach Tin House with the project and pitch it to them?

MK: No…It’s a strange story. I think I have a tendency to stretch it out too much. I had started doing the art just for myself; it was a personal obsession. And I would put it online immediately, right away with page one. My friends and family all knew that I was pretty passionate about art, and I wanted some accountability. I had made a big deal out of the fact that I was going to do one illustration per day, per page, and I knew that if I started missing a few days they would call me on it. They would send me an email, or my mother would call me and sort of yell at me to get back to work. I started in August of 2009, and sometime, I think in February 2010—this was about five or six months into the project—some guy from Brooklyn emailed me and asked me if I wanted to give this presentation about it. And it sounds all official, but it was a lecture in a bar, called Pete’s Candy Store and it was part of this thing that this guy was running, called O.C.D. He said it stood for “Open City Dialogues,” but obviously, the joke (OCD) is intentional, because he would find people that had very strange obsessions, and he would invite them to come to Brooklyn and sort of talk about it, as part of his lecture series.

My wife and I try to go to New York City at least once a year, and this was just good timing, so I said, “Sure, I’ll come out and do it.” It was really packed, I was really, very pleasantly shocked. The reception was really positive. So, for someone like me, who is a complete unknown – a self-taught artist from the Midwest –to come out to Brooklyn, one of the centers of the art world, and have this incredibly kind reception from a crowd with people in their twenties to a few academics! I went home, and very shortly after that I got an email from a book illustrator named Sophie Blackall; she had seen a write-up of my talk in one of the city papers, the free papers. But she primarily illustrates children’s picture books, and she’s a big, obsessive Moby-Dick fan too. She tries to work a whale into every picture book that she does.

BLVR: Wow!

MK: So anyway, to make a long story short, she said ‘My friend is an agent, and I think that this would be a really great book. Do I have your permission to refer this project to him?” I thought it was a kind of weird question, because it’s all online—I mean, it’s not like I can say “No, he can’t look at it.” I said yes but I gave him a hard time for a little while, because I was real suspicious of agents, you know? And so I was really kind of a jerk to him, but he was really persistent in a good way, so, finally, I signed with them. within two days, he called me back, on my birthday and said that he had an offer from Tin House. And I was very excited, because I was very familiar with the quarterly. You know, Tin House was a publisher that I already really liked.

BLVR: That’s great. Could you explain the sort-of…birth story of Heart of Darkness? From what I understand, Tony [Perez, editor at Tin House] said that thatis the book that they contracted from you, out of all of the illustrated series, which have mostly been artist-driven. So, was it your pitch for Heart of Darkness, or did they sort of approach you about that project?

MK: I was still interested mainly in illustrating books that were already written – Heart of Darkness was one of them, and there were four others. And Seth my agent talked to Tin House, and it went—again, it happened amazingly quickly, you know, in early 2012, they took me on for Heart of Darkness. You know, Melville and Conrad had some similarities. Anyway this was the first time that I was making art specifically for publication. So at that point, in a way, it became a job, so that changed how I worked in some interesting ways.

BLVR: Could you explain a little more about how your creative process differed when illustrating for Heart of Darkness from the way that it was when you were doing Moby-Dick?

MK: With Moby-Dick, actually, I felt that I had a lot more freedom. And I think that the creative process for each one of these projects, in a sense paralleled the books themselves. So, for a book like Moby-Dick, which is this massive, sprawling, mosaic of a book, you know, you have these passages that are told from the point of view of Ishmael; you have these passages that are almost like a theatrical production; you have these passages with an omniscient narrator that couldn’t possibly be Ishmael, because, you know, he’s overhearing, the narrator is hearing Ahab speak to himself in his cabin, and there’s no way Ishmael could do that. So you have this crazy structure in Moby-Dick where it’s almost like Melville chopped up ten different novels and smashed them all together, you know, in a variety of different ways. And that’s where people joke, saying that if Melville had written Moby-Dick today, no editor would publish it. They would send it back with all sorts of rewrites, saying, “Well, the tone doesn’t match here, and you change points of view here,” and so on. And so, because of that wildly varying tone and that wildly varying structure, and, you know, there are parts of Moby-Dick which are hugely amusing. I mean tremendously funny, howlingly funny. And then there are parts of the novel which are incredibly bleak. And incredibly nihilistic and terrifying. So, you just, you have literally everything within Moby-Dick. Everything that you could imagine is somewhere in that book.

My creative process and my illustrations really followed that, they paralleled that structure. I let myself use any kind of media that I wanted, whether it was pencil or ink or acrylic paint or stickers or nail polish or spray paint. I allowed myself to use any kind of style of representation that suggested itself to me. So, some of the images are fairly realistic; some of the illustrations are almost abstract; some of them are very graphic, like you would see in a comic book… I felt that that really fit the tone of the novel, and I had this freedom to do whatever I wanted.

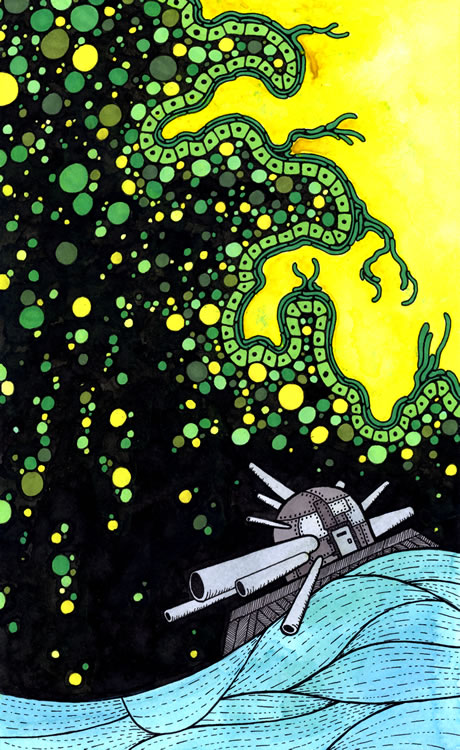

Heart of Darkness, on the other hand, is a much shorter work. Only 100 pages, compared to almost 600 for Moby-Dick. With Heart of Darkness, there’s this incredible, kind of terrifying, singular purpose to it. You know, there are no diversions, there are no digressions. It’s this steadily-drawn, farther and farther down novel, as Marlow is journeying down the river in Africa, it’s just the single-mindedness of the writing. There’s just a single kind of stress, the incredible consistency, which makes the novel so incredibly powerful. There’s no escape, there are no moments of levity, there are no digressions, there are no asides. There’s just this search for Kurtz and this terrible, awful confrontation at the end, and then this soul-searching. And so, I’ve made a deliberate attempt with Heart of Darkness to keep the illustrations very, very visually consistent. They were all pen and ink; I used a pretty similar color palette the entire time. You know, with Heart of Darkness I really wanted color to be a part of the illustrations…almost a character in the illustrations. So, I kept the colors very, very consistent, and I thought a lot about what they would suggest, how they would evoke feelings in the viewer.

All hundred of them follow very, very much after the other, in a way that I think makes it almost like a storyboard. Not quite, but almost, like a graphic novel. I feel like you could understand the narrative of Heart of Darkness just by looking at my illustrations, whereas, if you are not familiar with Moby-Dick, you might occasionally wonder what was going on in some of the pieces.

BLVR: How long have you been working on Heart of Darkness?

MK: So for Heart of Darkness all my friends were joking, “Oh, it’s only 100 pages, you’ll be done with that in three months! You’ll be onto the next book.” Well, you know, for obvious reasons I didn’t want to subject myself to that same brutal pace I had for Moby-Dick, because it’s very difficult to have any kind of life. And Heart of Darkness is such a corrosive book, you know, it’s such a venomous, toxic book. There’s so much ugliness in it. And by stretching it out, and by working more thoroughly through it, and creating these more involved illustrations— it was absolutely hellish to work through genocide, and colonialism, and the rape of Africa, and all this terrible violence that’s going on…

BLVR: Is there anything you would do differently in either of the projects, if you could do them over?

MK: Working on these illustrations is, in many ways, like being a reader. And sometimes, we go back and we reread passages or we reread chapters, but for the most part as a reader our progress through a book is linear—you know, we begin at the beginning, and when we reach the end, we’re done. And we may think back, but for the most part we’ve had this very one-directional journey through the narrative.

I haven’t gone back for either project and thought about them a great deal, because I feel like I started at the beginning, I went through, and then I came out the end. And, you know, both of them are…Sometimes, as a reader, you feel lucky to be alive, at the end. I know that sounds kind of strange, but when you read that intensely… The truth of it is this, I could easily go back and do another 600 illustrations for Moby-Dick, because that book, I think, is so incredibly rich, and so visual, and so exciting, and so thrilling that it’s almost bottomless, how much I could do with that.

With Heart of Darkness, other than maybe not doing it, because of how difficult it was…Again, I would not do anything differently. I’m really proud of both of these bodies of work but I especially do not think they’re the creative definitive vision of either one of these books.

BLVR: So, what do you think that the Tin House illustrated editions do differently from other illustrated reprints of classic works?

MK: At no point was—did either of my editors, Lee Montgomery for Moby-Dick, and Tony Perez for Heart of Darkness—at no point did they step in and try to change my vision, try to influence the illustrations, try to get me to change something for reasons of marketability or popularity. You know, they gave me complete freedom, complete support, both of them were always there to answer my email questions, within hours. I mean, they were just unbelievably fantastic to work with. They really seemed to not only care about the work that they’re publishing, but they seem to really care about the people that are publishing it, as well. And I think—from some of my friends who have done illustrations for other publishers, some of whom are huge, you know, publishers like Random House, and Norton, and Penguin, and so on—you know, at times, those are as impersonal as petroleum corporations.