An Interview with Ben Kopel

In his book Victory, Ben Kopel’s poems present the grim and petty unapologetically – “sad, thin-skinned kids” huffing Pine-Sol in a parked car, the necessity to “stay up late / smashing bottles / against the levee / for nothing” – but there’s also a fierce refusal to dismiss hope. Even the broken and chaotic is edged with grace, as in “Because We Must” – in which the voice requests “a prayer, now / & at the hour of our death – / fill me with yr light inside this car.” We spoke on a September afternoon over Gchat, me in Los Angeles, him in New York.

— Stephanie Pushaw

I. THE SINCERITY OF THE SAMPLE

BEN KOPEL: I was wondering how the book popped up on your radar?

THE BELIEVER: A while back your poem “There Is A Question I Am Waiting Forever to be Asked” was going around a certain subsection of the poetry tag on Tumblr, and I loved it and bookmarked it and forgot about it. And then a friend of mine who knows of your work sent me some more of it. I ordered the book online. So the answer, I guess, is: internet serendipity combined with the smallness of the world. Also, I think that friend saw you at a bar recently.

BK: Ah! Her! Yeah, I remember! I was all like, “Oh wow, the internet works!”

BLVR: Yeah! And one of my questions was actually how you feel about that sort of chopped-up sharing of cultural artifacts. Starring a song on Spotify without hearing the whole album, or reblogging a single poem on Tumblr, for example.

BK: Context is ultra-important, but I don’t think that necessarily means the ‘original’ context is more important than the one in which you discover the artifact, be it a poem or a pop song. We can’t help but create our own context for the things we love. Personally, I love how things like Tumblr allow poems and songs and video bits to be shared and spread all over the place. Yes, I do hope that people do what I always do and research and scratch around to find out where these things came from. I’m still kind of hopeless when it comes to that. When I hear a song or read a poem, I have to dig through the internet to find out everything I can about it. Usually that leads me to my new favorite whatever-it-is. You know, something new to obsess over.

BLVR: The whole mess of constant saturation and updating feeds often serendipitously ends up with us being on the right screen at the right time. Speaking of which, do you feel as though this sort of new way of approaching cultural snippets – largely via the internet – celebrates our remix culture? I mean, some of your poems reference or share titles of songs and albums that have obviously influenced your life. I’m also thinking of your Subterranean Homesick Blues homage. Where does the response end and the “cover version” begin?

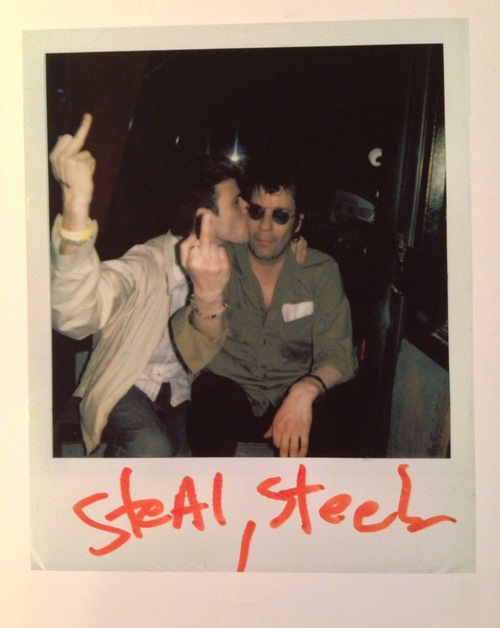

BK: When I was still in college, I was lucky enough to see Paul Westerberg play a show in New Orleans. Afterwards, I snuck back to his bus and ambushed him. I asked him what the secret to being a great writer is (God bless youthful bastard bravery). His response: “Steal everything.” A friend took a Polaroid of the two of us. Paul signed it “STEAL, STEEL.”

But to be more direct, I totally believe in the sincerity of the sample. Partly because it’s my way of saying “Thank you” to my heroes, and partly because it’s the breadcrumb trail for anyone out there reading my poems. I want to guide them to the words and sounds and images that mean the world to me. There are no secrets. Everything comes from something. To sample Jarmusch sampling Godard, it’s not where you take things from. It’s where you take them to.

BLVR: You’ve mentioned before your admiration of Patti Smith, and one of her quotes even provides an epigraph for Victory—“I’ll give you one tip: use your fists.” Donald Barthelme said that “anathematization of the world is not an adequate response to the world.” So I’m wondering, what is?

BK: Cursing the world for being the way it is won’t get us anywhere. But I do want to admit to what it is. I want to admit to what I am. And, yeah, that includes some negative things. There’s a violence in this world and in me, myself. There’s also an anger there. But I’m trying to use these poems to get the balance right, right? For every inch of fear, there has to be some bravery in there to ballast it. Is ballast a verb? I hope it is. It is now. We live in this world, but I think poetry springs from the world that lives in us. Is it a better world? I don’t think it is.

BLVR: The world that lives in us?

BK: Yeah, I don’t know if it’s better, because we need people. We need each other. And that’s what I’m trying to get at most of the time. In my poems, so often you have these solitary figures trying to find some sort of connection. They lash out, but they mean well. I don’t want to sound like I think poems are better than people. People are what matter the most.

II. NO ONE WINS UNLESS WE ALL WIN

BLVR: There’s that moment in “Blue Light Plastic” where Burn Victim #4, this anonymous extra who undergoes the same rigorous preparation for filming as anyone else, holds the speaker down and he sees a member of the studio audience “fall silent and at once become / the most beautiful thing in all of Los Angeles / for the first time in his entire life.” That’s the kind of moment that transcends the quiet desperation of most peoples’ lives, where you’re aware of it and it’s rare and beautiful and hard to describe but you can only try.

BK: Exactly. That’s a big part of the title of the book. It’s a book called Victory, and yet most of the time ‘victory’ seems so unlikely. Which is all the more reason to fight with all the hope you have. Tooth and nail and heart and sleeve.

BLVR: Use your fists!

BK: You know the best thing about that quote? It’s actually something she said to Bob Dylan. He was all like “Patti, when I don’t have a guitar in my hands and I’m at the microphone, I have no clue what to do with my hands.” So she told him he had to ball ’em up, like a boxer in his corner. See? Context is crazy. Elvis Costello is another guy who looks totally lost at the microphone without a guitar in his hands.

BLVR: Did you ever want to be that guy at the microphone?

BK: Yes, very much so. But, truth be told, you would be hard-pressed to find a worse musician. But I do actively try to bring that kind of Patti Smith/Joe Strummer/Bruce Springsteen energy to every reading. That’s doesn’t mean I’m up there doing all these Bob Pollard high-kicks or James Brown splits, but I want my audience to know that, when I’m up there, I mean every moment of it. And yes, I pray to St. Joe that that comes across on the page as well.

BLVR: A large thing that drew me to your poetry was that energy contained within it. It reads like – and I believe someone may have brought up this point in a review or an interview with you before – but it reads like how lyrics tend to sound when they’re being carried to the listener via the medium of music. And sometimes when you look them up they lose that relevance they only had carried on the back of a really good beat or whatever. So poetry is sort of cutting out the middleman, relying on the words themselves to convey that sense of urgency that music gives us.

BK: The poems I’m working on currently are trying to get even closer to that kind of urgency. I’m even writing them the way I transcribe lyrics when I text them to my friends or post them online. I want to be able to keep the momentum going while still using ‘breaks’ to allow the reader to make sense out of what is happening within the text.

BLVR: There’s a unique and tender attention paid to the underdog in Victory—sort of aligning with this theme of training up to the fight, even if you have no hope of winning it. What fascinates you about the also-rans?

BK: It’s the ones who are, in a word, fucked, that inspire me the most. The ones with nothing left to lose, those are the honest ones. They mean it because this is their last stab at meaning anything. They haven’t been heard, and yet they have so much to say. They know what that’s worth…their words…their actions. They want them to count. The beautiful losers, that’s my tribe. I guess I just believe that there is a lot of dignity in getting the crap kicked out of you, then looking up at the camera and spitting out a tooth or two and smiling. Are you a Mountain Goats fan at all? Transcendental Youth is basically the soundtrack to Victory, even though it came out a year or two after the book. He’s a survivor and he wants us to survive as well. No one gets left behind in those songs. No one wins unless we all win.

BLVR: What is that song called, that’s not on an album, but he performs it live sometimes?

BK: You Were Cool?

BLVR: Yes.

BK: “It’s good to be young / but let’s not kid ourselves / it’s better to pass on through those years / and come out the other side / with our hearts still beating / having stared down demons / and come back breathing.” Survivors recognize other survivors. John Darnielle said that, and that’s what ‘Victory’ is there for, to me. To say, “Hey! I see you! You’re here! You made it!”

BLVR: The intro to that song is also relevant to the discussion of originality and stealing— “this is a song with the same four chords / I use most of the time / when I’ve got something on my mind.” It’s not the medium; it’s the message, and why dress it up?

BK: Yeah, when I tell people the book I wrote is a book of poems, there’s often this moment of, “Oh…those. Yeah, those aren’t for me.” And I always just want to tell them, “No way! They are 100% for you! I have something to say and I want you to hear it. I am not trying at all to make you feel confused or lost.” Life is confusing enough. And I’m not saying poems shouldn’t be confusing. But I am saying that I think there is a productive confusion that comes with reading poems that creates opportunities for surprise and joy and recognition within a reader.

BLVR: I think a big issue a lot of people have with poetry, especially contemporary poetry, is that they’re intimidated by this sort of internalized need to understand everything about the poem, to dissect it and see how it works. But a large draw of poetry, at least for me, initially, was because of that real exhilaration in the uncertainty, in just being affected by the imagery, by whatever combination of words seizes and shakes you.

BK: Exactly. It’s there to be enjoyed! “If it ain’t a pleasure, it ain’t a poem.” William Carlos Williams said that. Poems ask you to do something daring: they ask you to enjoy them. They want you to get excited! Enthusiasm counts for a lot in this life. Poems know that. Sometimes poets forget that, but luckily I think we’re living in a world full of poets who want people outside of the academy to get stoked about our little language grenades.

III. METAPHOR AS MISTAKE

BLVR: You taught English to high school students in New Orleans. What did you use to get them engaged with literature in a way that went beyond the whole “here’s how to prepare for the AP English Lit exam” spiel?

BK: The best part about teaching those kids was A) that they’re amazing and generous and not cynical in a way that not many give young people enough credit for and B) being able to call upon the community of poets that I call my friends. Specifically Emily Pettit, Nate Slawson, Dorothea Lasky, and the patron saint of all of us, Dara Wier. By assigning my kids new(ish) books by people I personally know and respect, I was able to plug those young men and women into the fact that poetry is very much a very real and extremely alive thing in the world today. They were able to email each poet questions and get honest to god answers from honest to god artists. Nate Slawson even sent hand-made YouTube videos answering every single one of my students’ questions. It was a wonderful experience and proof that we are all writing and reading and publishing at a very exciting and open moment in the era. The students got to see and hear and read the poets as people, not just names.

BLVR: Being able to connect to the writer beyond their just being a name in ink on a page definitely reanimates the message in a more specific way. Are you familiar with Walker Percy’s Essay “On the Death of the Creature”?

BK: Jeez, no. But I love death and I love creatures and I love Walker Percy, so I’m ¾ths of the way there, right?

BLVR: I just dug it up, it’s called the Loss of the Creature, not Death, but anyway.

BK: I’m less of a fan of loss. I have that collection, though. ‘Metaphor as Mistake’ was a big eye-opener for me from that collection. It’s an essay basically about embracing mistakes as a way of finding your own voice within the language you’re working with. Kind of like when you mis-hear a song lyric, then you read the liner notes, realize you were way off, but you like your line more than the ‘real’ thing. Basically, how I’ve written a lot of my poems. I make a mistake, admit to it, then use it.

BLVR: And misinterpreting a lyric, of course, has everything to do with the listener and their own subjective interpretation of a song. But what – to go back to the Jarmusch/Godard thing – is important is where the listener takes that mistake to, which I think is what you’re saying about your own work. The way into anything is sort of secondary to the way out of it, as it were.

BK: Yes, the listener/reader/writer needs to take that mistake and walk it somewhere new. Somewhere only they themselves know about, but they are willing to share with the rest of us.

Ben Kopel is the author of Victory and a chapbook, Because We Must. He will be reading at Mellow Pages in Brooklyn this Thursday, October 24.

Painting: Justin Clumpner

Polaroid: Jamie Hopper, Christie Matherne, Robbie Howton, Chris Bannerman

Photo: Mara Gold