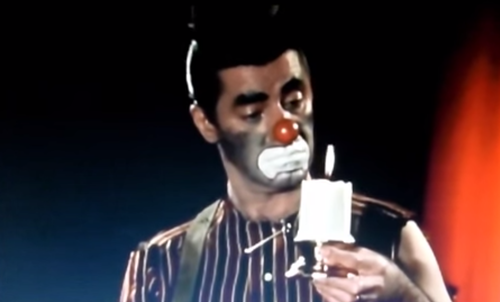

This August a clip from The Day the Clown Cried—the notorious Jerry Lewis passion project—surfaced on YouTube. The never-released film supposedly tells the story of Helmut Doork (Lewis), a past-his-prime German circus clown who finds himself imprisoned at Auschwitz where he lifts the spirits of Jewish children who are sentenced to die. “We don’t talk about that [film],” he told an interviewer in 2009, “not even if I found out you were one of my sons.”

Clown is rumored to be locked in a safe somewhere, and only a handful of people have ever seen it. One of those people is Harry Shearer of Simpsons and Spinal Tap fame, who told Spy magazine in 1992 that “this movie is so drastically wrong, its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is.”

Nothing kills a joke like talking about it. (Contenders for the least-funny texts in existence include Freud’s The Joke and Its Relation to the Unconscious and Bergson’s Laughter.) Explanation and exegesis are a comic’s worst nightmare; as soon as you talk through a joke, its essence disappears and it is gone forever.

The opposite might be said about the Holocaust. The rhetoric of “Never Forget” and Facing History and Ourselves curricula revolve around keeping memory alive through dialogue. “Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented,” wrote Elie Wiesel.

So what, then, of Holocaust humor? Can such a thing exist, and if so, how do we engage with it? Is talking about it self-defeating or self-fulfilling?

Perhaps the better question is this: why all the clowns? Lewis’ film is by no means the only Holocaust movie to place a jester figure at its center. Think of the slapstick in Life is Beautiful, or Robin Williams in Jakob the Liar. The German Holocaust tragicomedy Hotel Lux opens with a cabaret. Extreme genocidal violence? Stick a clown in there, see what he can do.

The twentieth century’s most famous clown, Charlie Chaplin, made a movie about Hitler, and it was the first film in which he spoke. The iconic silent tramp was suddenly no more. But he spoke only because of what he didn’t know; Chaplin later stated that had he been aware of concentration camps at the time, he would never have made the film at all.

The clown is a physical comedian and says little if anything. He does not analyze and probe like a standup; he gets hit with a pie in the face. “Why didn’t you yell for help?” asks...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in