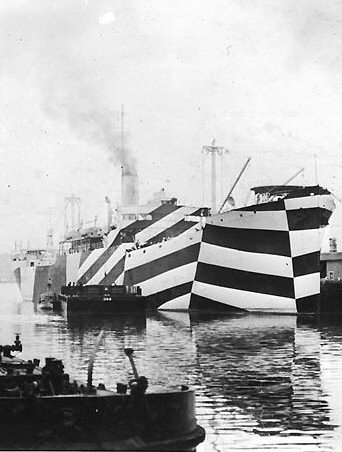

USS Mahomet in port, circa November 1918.

Camouflage was designed to hide things, but how it changed our worldview may be its most revealing surprise. This five-part series examines the history of camo, from its humble origins to its current ubiquity. Catch up with Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V.

PART THREE: Guile and Ghillie

It wasn’t cost-efficient during World War I to mass-manufacture camouflage fabric—it was all hand-painted. That mind-boggling fact explains why most soldiers wore solid drab uniforms in World War I. Camouflage crept into the ranks as sharpshooter garb, conveying elite status in much the way drab originally did.

The Germans decorated their special-issue Stahlhelm (steel helmets) in a crisply disruptive pattern; trench-assaulting storm troopers wore these starting in 1916. Less romantically, “ghillie suits” worn by snipers turned them into walking shrubs. (The name stems from a Gaelic term for landowner servants who hid in wait to snag poachers.) Disruptively patterned ghillie bodysuits came with matching balaclavas and three-fingered mittens (to accommodate the trigger finger); soldiers stuck greenery into the fabric to complete the ruse. The look perfectly combined a Klansman-like severity with a certain hangdog awareness of how ridiculous one looked when removed from his perch. Still: hot, inconvenient and mockable as they were, a good ghillie suit really worked.

Sea and Air

In 1917 German U-boats successfully torpedoed 23 British ships weekly—55 during one week in April alone. British Lieutenant Norman Wilkinson’s solution, “dazzle” camouflage, ushered in a newly visible era for camo. Wilkinson described his insight in his autobiography:

…Since it was impossible to paint a ship so that she could not be seen by a submarine, the extreme opposite was the answer—in other words, to paint her, not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading.

Submarine shooters needed to estimate a ship’s direction, speed and location to calculate where to shoot. Dazzle, it was hoped, would throw off these estimates, increasing the odds a torpedo would miss its target.

Allied Navies took to dazzle keenly, testing patterns on miniature boats in simulated conditions before daubing up a fleet. Airplanes sported countershaded undersides to blend into the sky, while their dazzled tops stood out in a confusingly artful way.

Dazzle paint wasn’t even the most outlandish idea for hiding ships. Thayer tossed out numerous ideas: an all-white Allied fleet that attacked only at night, schemes for giant concealing nets or tarps daubed with clouds. Others proposed disguising ships as whales or hiding them with mirrors. Thomas Edison wanted to conceal ships as floating...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in