Nanny of the Jamaican Maroons, pictured on a $500 Jamaican bill.

Camouflage was designed to hide things, but how it changed our worldview may be its most revealing surprise. This five-part series examines the history of camo, from its humble origins to its current ubiquity. Catch up with Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V.

PART TWO: Out of the Drab

European armies wore bright uniforms until the mid-18th century, when the invention of rifles—a more accurate weapon than muskets—allowed sharpshooters to pick off their enemies, provided they could get within firing range unobtrusively. Austrian Jägers (literally “hunters”) dressed for the job in light gray, while the British 95th Rifle Regiment wore dun-green.

Khaki entered the lexicon in the mid-nineteenth century, when soldiers in the British Indian Army began to dye their white duds with tea and curry. Named for Urdu and Persian words for dust, khaki was less visible than white and lots more practical. This drop in sartorial pomp gave the Brits a transformed look: in 1849 a British gunner halted friendly fire in Sangao, marveling: “Lord, Sir; them is our mudlarks!”

Practical and unobtrusive as drab uniforms were, militaries only adopted them broadly around the turn of the century. Here the suggestibility between man and uniform is laid bare: fighting in drab attire seemed overly casual, even cowardly. Yet camo ultimately won out for two reasons: it reduced casualties and made recruits feel war-ready, albeit for a different kind of war. It caught the Europeans up with scrappy guerrilla tactics like those used by Jamaican Maroons, African slaves who forced their British colonists to grant them independent lands in the 18th century. Led by Nanny, Jamaica’s only female National Hero, the Maroons used camouflage to foil the British at every turn: cladding themselves in foliage, communicating via birdcalls, even disguising their trail with lemon-scented leaves to confuse British bloodhounds.

Cloak-and-Dagger

“The birth of modern camouflage was a direct consequence of the invention of the airplane,” wrote Tim Newark in his 2007 book Camouflage. Worried about aerial reconnaissance, militaries first used camouflage to hide equipment and locations, not people. (Aerial attack hadn’t yet emerged as a threat.)

This mission comes through loud and clear in a 1918 British booklet on camouflage: “The camera is a most accurate witness, and a photograph will always record something. The art of camouflage lies in conveying a misleading impression as to what that something means.”

The French were first to organize camouflage units around 1914. The names of key camoufleurs reeked of cloak-and-dagger: France’s first camo unit was headed by Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola, a Parisian portraitist given to wearing white gloves in the trenches. The Brits’ lead camoufleur in World War I was mirror-man Solomon J. Solomon.

The term “camouflage” was first popularized during World War I. Roy Behrens’ delightful 2002 book False Colors: Art, Design and Modern Camouflage gives its layered etymology. Dating to 16th century France, a camouflet was a practical joke. It involved “lighting the tip of a hollow paper cone, then holding the opposite smoldering end under [a] sleeper’s nose. The stupefied sleeper would spring to his feet as soon as a noseful of smoke was inhaled.” Camouflet later referred to a “small but lethal powder charge by which a tunneling enemy troop could be entrapped beneath the ground.” It also stems from the French verb camoufler, to make oneself up for the stage.

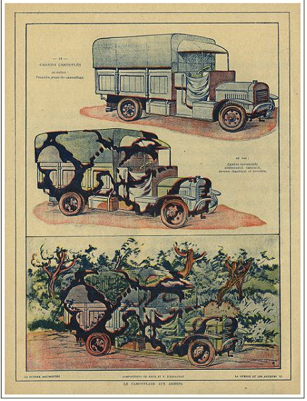

How to camouflage a truck, from La Guerre Documentée, vol. IV, c. 1920. Courtesy of Tim Newark’s collection.

World War I

World War I camo tactics were basic: hand-painting tanks, trucks, and cannons in disruptive patterns matching the landscape. Camoufleurs also tossed netting laced with raffia ties over valuable buildings, à la foliage, and taught troops commonsense tips to reduce their aerial visibility: smoothing over truck tracks and cannon blast marks, parking tanks under trees to reduce telltale shadows, and so forth.

But camo grew increasingly baroque as the war progressed and its mystique increased. Entire battalions of howitzers might be shrouded in cover resembling fake-farmland. Munitions factories stamped out decoy heads by the thousands, to be poked provocatively above a trenchline, attracting enemy fire that betrayed his location. A mania for false trees as observation posts swept the regiments; an actual tree in a battlefield was felled in the wee hours, and a hollowed-out replica erected in its place (with a soldier smuggled inside it). This particular ploy got Charlie Chaplin into hot water in a scene from his 1918 war film Shoulder Arms: his snooping proximity to a German campfire takes a hair-raising turn when the Jerries run out of firewood. (Watch the clip here.)

A still from Shoulder Arms (1918) by Charlie Chaplin

Jude Stewart writes about design and culture for Slate, the Believer, Fast Company, and Print, among other publications. Her first book ROY G. BIV: An Exceedingly Surprising Book About Color is now available from Bloomsbury. Follow her on Twitter @joodstew.