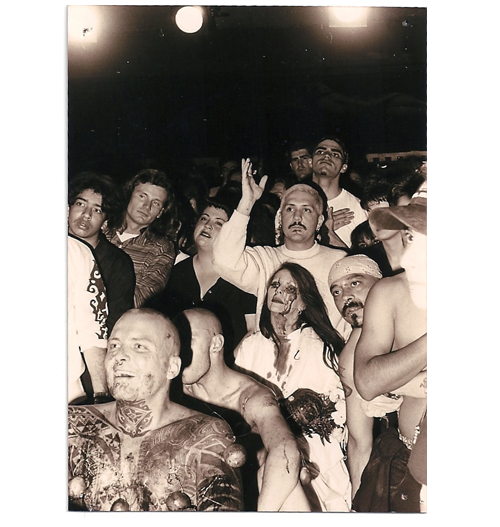

(The audience at Sin-a-matic in Los Angeles, c. 1994. Photographer unknown.)

(The audience at Sin-a-matic in Los Angeles, c. 1994. Photographer unknown.)

I first encountered Jennifer Doyle’s work through her essay “Queer Wallpaper,” written for a survey textbook on contemporary art. Meant as a pedagogical primer on queer theory and queer politics in art, the essay was personal, affecting, and for what felt to be most important at the time, it conveyed what it might mean to write about visual art with an actual affinity and care for writing itself.

So when her newest book Hold It Against Me: Emotion and Difficulty in Contemporary Art was announced, I followed the release date assiduously, eager to see how Doyle weighed in on “controversial” art (usually performance) by figures like Carrie Mae Weems, David Wojnarowicz, Nao Bustamante, Franko B, and Ron Athey. The book follows up on theories of affect and emotion that have gained large amounts of currency in the humanities, but resolutely sticks to a pedagogical, writerly, and accessible style of criticism meant to complement and expand the ‘difficult’ work on display.

I spoke with Doyle over a long Skype conversation, jumping to touch not only on the points in the book, but on her experience programming, attending, and writing about performance art in my hometown of Los Angeles. Doyle’s current book project is titled The Athletic Turn: Contemporary Art and the Sport Spectacle.

– Joseph Henry

I. THE FLINCH MOMENT

THE BELIEVER: The emotional quality of art is never the same for any one person – one viewer could find an artwork difficult or challenging and another could be bored or unimpressed. How do you approach emotion as subject in Hold It Against Me?

JENNIFER DOYLE: One of the things I’ve been saying is that we’re so used to using emotion or feeling as a kind of synonym for the subjective–and I think people that work in art criticism know this well–but there’s a subjective dimension to any critical practice. I’ll start with that: it’s not necessarily that the emotion we encounter in or around works of art is so much more subjective than elsewhere so much as it is the case that we’re very particularly invested in emotion as the place upon which we encounter the subjective.

I’m interested in artists who work with that kind of head on, rather than say, represent emotion for us. Their work has a particular character that makes it impossible to understand it without thinking about the politics of emotion, or the politics of emotion as historically or politically conditioned. This kind of work sometimes forces a confrontation, too, with the politics of taste – I love the performance artist Franko B’s work. It...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in