Part I.

The following interview first appeared, in part, on episode one of The Organist, the new podcast from the Believer and KCRW. You can hear the episode here and hear the full Saunders interview here.

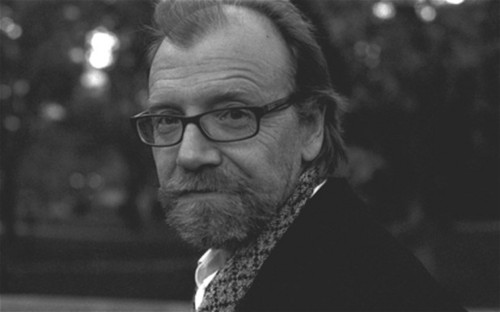

– Ross Simonini

THE BELIEVER: After listening to you read your work aloud a few years ago, I’ve since had your voice in my head whenever I read your work. Have you ever had this experience with a writer?

GEORGE SAUNDERS: Steve Martin is somebody… when I was younger I read his book Cruel Shoes and then I saw him live afterwards and the whole book kind of came alive in his voice. Yeah, for sure.

BLVR: Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

GS: Well, for my work I’m not sure, because I’ll read the story “Victory Lap” sometimes and some people will come up and say, “You know, I—I liked it when I read it, but when I heard you it made more sense.” So there you’re like, Well, I don’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing. I hear these voices differently than I do them. I’m sort of limited as an actor. Like I have about three voices I can do. When I’m writing it I hear a much more subtle version. But, you know, I’ve got basically four switches I can throw, four voices.

You know, I grew up in Chicago and one of the things you can do for credibility there is—not really imitations, but you could sort of riff on an invented character. So somebody would make up a guy and give him a goofy name. And then we’d banter back and forth in his voice. You only did it with people you were really close to because it was easy to step over into humiliating territory. But that was kind of a fun thing to do, a kind of improv where you’re not only doing a funny voice but you were characterizing as you went. I was on a basketball team but didn’t play, so me and my friend, we made up this whole back-story for this team that we were sort of rivals with and we had, you know, we literally had sheets of paper with their home life on it and the names of their siblings. And these poor kids, they had no idea. So they’d come out and we’d do their voices. It was not that funny, actually. Our teammates got irritated with us because we were kind of being, you know, a little bit thespian-ish and it didn’t seem to be affecting the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in