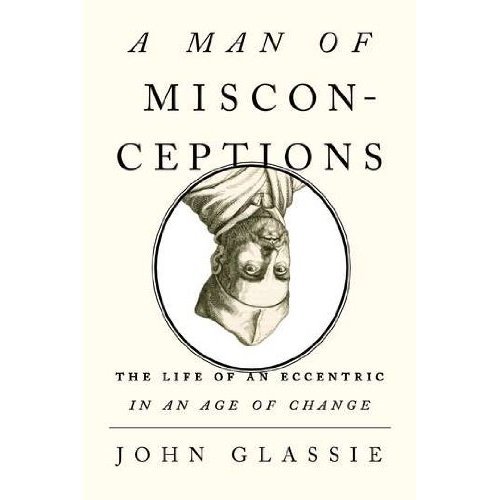

Regular Believer contributor John Glassie’s new book, A Man of Misconceptions: The Life of an Eccentric in an Age of Change, which is being released this week, tells the story of the seventeenth-century Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher. Kircher was the original nutty professor: an eccentric, obsessive, accident-prone intellectual, who promulgated many ideas — secret knots of magnetic influence, universal sperm — that from a modern point of view just seem strange. But he was also an utterly brilliant and erudite man: he published thirty books on subjects including geology, mathematics, history, cryptography, and acoustics; he was probably the first person to examine blood through a microscope; and, as this excerpt from the book shows, he also sometimes collaborated with the baroque artist Gianlorenzo Bernini.

Athanasius Kircher’s successful investigations into magnetism, optics, and music in the 1640s were “grounds for praise of God,” as he later put it, but they also offered surprising “fodder for tribulation,” and may have even brought about some paranoia on his part. (Around this time, Kircher outfitted his bedchamber at the Jesuit college in Rome with a “speaking tube” through which he could eavesdrop on conversations in the courtyard below.) Those who had always been skeptical of him, he recalled, “attacked me anew with fresh accusations.” The charge: he’d been concentrating on those other subjects because he wasn’t getting anywhere with his most important work, “as if abandoning all hope of addressing Hieroglyphics on account of its impenetrable difficulty.”

Kircher was approaching middle age, and it had been many years since he’d taken on the project of trying to decipher the texts of the ancient Egyptians, more than a decade since he’d promised in an earlier work that he would soon be able reveal the secret mystical wisdom that he and many others believed was encoded in the hieroglyphic inscriptions. During this time his vision for Egyptian Oedipus, the masterwork that would contain it all, had only grown more and more ambitious, and more and more expensive to execute. It would have to be longer than he originally thought. Many exotic typefaces were required. More artists and engravers were needed to render the illustrations.

But now, he said, God provided “an utterly marvelous manner” for him to resume his hieroglyphic activities and to “elude the empty machinations” of his enemies. Events led to not only the publication of Egyptian Oedipus but to Kircher’s collaboration with Gianlorenzo Bernini on what many people regard as Bernini’s greatest work, the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (Fountain of the Four Rivers) in Rome’s Piazza Navona.

In 1647, Pope Innocent X decided, “for the immortality of his own name,” as Kircher wrote,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in