One of the things that keep a person reading a book is “suspense” – you don’t know what’s going to happen next and you want to know. Or there’s a general feeling of tension that mysteriously holds you. I hate this in a book. It feels like eating salty chips. No, you can’t eat just one. You eat more and more without wanting to. But so what? When I turn the pages of a book that quickly, it’s often because what I’m reading feels as bad for me as a chip. I don’t admire the author’s technique. I resent the suspense for keeping me there, when I would rather be somewhere else (or, if I love the book, for not letting me linger on what I’m loving; for forcing me to rush).

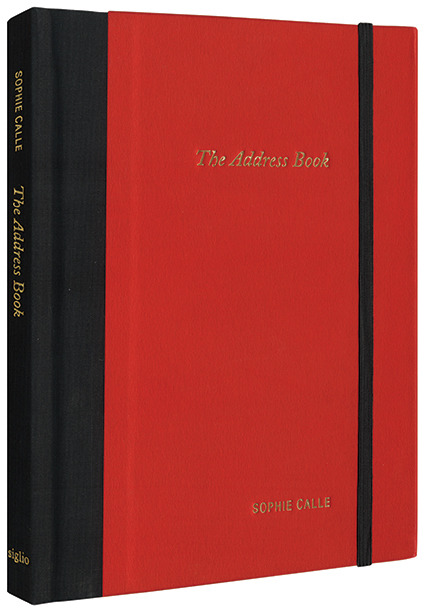

In Sophie Calle’s The Address Book, created in the 1980s in France and now being released as a book in English for the first time, one turns the pages that fast. You gobble it up like a bag of chips, but instead of it being bad for you, it’s just bad. I don’t mean that as a criticism. I mean, it’s wicked. It’s wonderful, brilliant, breathtaking – but bad.

In 1982, the artist Sophie Calle found on the streets of Paris a man’s leather-bound address book. She was curious about its owner, but that curiosity didn’t lead her to call him up, meet him face-to-face, and return the book. Instead, she decided to make appointments with the people whose names he had collected in the book, and ask them about him, taking notes, writing up briefs of the interactions. Each meeting became its own article, published in the prominent French newspaper, Libération, over the course of a month.

This is how she did it: she would call someone up, explain that she had found an address book in which their name was written, and ask to meet with them to talk about the owner, saying she would disclose the name of the book’s owner only at the meeting. She called former lovers, friends, family, distant acquaintances. Some reacted with outrage at the call, others agreed to meet. One has feelings about these people by their initial reactions. (I felt most admiring of those who yelled at Calle, suspecting I would not be one of the yellers.)

The suspense and tension in The Address Book comes from seeing someone do something so outrageous, so morally suspect, so ethically questionable. Does the artist have the right to do whatever she wants if it adds to our understanding of who we are (which this book does)? The tension in this book doesn’t come from the dynamic between the characters an author has invented, but out of the real dynamic between the author (Calle), the man about whom she is writing, and us.

Amazingly, a unified portrait of the man (Pierre D.) is created through the successive interpretations of him. He becomes more and more clear; it’s a sometimes paradoxical image, but more often consistent, and even the paradoxes make him seem human. When you’re writing a novel, making up a character, one of the difficulties is in how many seemingly personality-incongruous things a character can hold while still seeming like a unified character. But because we know this man exists as a man, one can stretch the elastic band of character traits and actions so wide. It makes him more real than if he was more “truly” unified.

Pierre D. is mysterious, admirable, reclusive, charming, stubborn, oblique, unique. Would every address book yield up such a compelling and complex soul? Are we all so distinct, as fascinating as Pierre? Or was this some act of grace from the art gods?

Calle spends only a few moments worrying about what she is doing. Her freedom is part of what makes this document such a thrill to see; an unrepentant criminal is more thrilling to witness than a repentant one. More different from us. Pierre felt her work was a great trespass, an outrage. He threatened to sue her and demanded the paper print a naked picture of Calle in retaliation.

I can understand why. A lot is revealed. The project’s illicitness is huge part of its meaning and effect; the suspense that exists in this text is the suspense of partaking in an act that feels wrong: we are invading his privacy each time we read her words, knowing he didn’t want us to. This book is only being published now because Calle agreed to withhold it from a second publication until after his death. Thirty years later, here it is.

The suspense that propels this book is not only, How far will Calle go? but, How far will I go with her? It does something unpleasant to you to you to read a book that a man could only bear to have exist once he was no longer on this earth. His letting her publish it a generous act; he considers her artistic legacy, and weighs it against his own desires.

Most books, most artworks, are so civilized, they hardly matter. They exist in the realm of please and thank you. But art at its best is a kind of gamble with civility, with ethics, with boundaries, with good citizenship, and with the question of what we can endure in life, and death.

– Sheila Heti

(The Address Book is available November 1 from Siglio.)