At 34, Faythe Levine is a doyenne of the independent arts and crafts movement: a documentarian, contemporary folk art collector, curator of Sky High Gallery in Milwaukee, and founder of the wildly successful Art vs. Craft fair, her 2009 film Handmade Nation garnered widespread attention; in the years since its release, Levine’s work has been courted internationally and featured in such publications as ArtForum and the New York Times. In October, Princeton Architectural Press will release Sign Painters, the companion book to Levine’s forthcoming film, The Sign Painter Movie. This latest project—a collaboration with filmmaker Sam Macon—is the culmination of three years spent interviewing and working alongside American sign painters, whose craft has helped shape the aesthetics of our public spaces.

When Faythe and I caught up in late June, it was midnight on the eve of a nasty Midwestern heat wave and several weeks sooner than we’d planned—I’d locked myself out of the Milwaukee house I was sitting and she offered up her guest room. The next day, over a supremely tasty breakfast of poached eggs, polenta, greens, and iced coffee, we talked a little bit about personal stuff and a lot about the people who paint signs.

– Eleanor Piper

(Doc Guthrie’s Classroom. LA Trade Technical College.)

FAYTHE LEVINE: The point of this project is to show people what it means to be a sign painter, what it used to mean, what they’re responsible for. When people say, “What do you mean, sign painters?” Well, at one point—look: you would never ask that of a plumber. You don’t think about plumbers; they’re just there. And so at one point, that was the case for this trade that basically doesn’t even exist anymore.

THE BELIEVER: If I may ask the obvious, why does it basically not exist? What’s changed?

FL: In the early eighties, the first vinyl plotters were introduced to the sign industry—one was called The Signmaker III or something. Like, “beep-bop!”

BLVR: Like a robot.

FL: …and at first the sign industry was not responsive, because these things were really expensive. But now what you have are these franchises where anyone can come in and open a shop with no design training. But design and layout are the basis of the trade! And so you go in and you get a banner for ten dollars, and they just take the copy and they cram it in and bust it out and there’s no thought about how it actually looks. It’s just about getting the copy onto the vinyl. So that’s one whole element of the demise of the trade.

BLVR: And yet the book deals with honest-to-goodness, working sign painters, some of whom incorporate—

FL: Well, yeah. So on the flipside, you have sign painters who can take this technology and use it as another tool, and still design a sign in vinyl and have it look good. But you just have these people coming along creating these signs that look like absolute garbage.

BLVR: Some of my favorite photographs you’ve taken are of these cruddy old signs and weird, amateurish graffiti. It seems like you’ve always sort of latched onto the odd ways that people express themselves in public spaces. After following professional sign painters around for three years, have your tastes changed?

FL: When we started interviewing people, something that surprised me was that my interest in signage was what a lot of skilled sign painters would call more like folk or untrained lettering.

BLVR: I’m thinking about all those daycare centers covered in badly-drawn Hanna-Barbera characters. Or like neighborhood barber shops and corner stores.

FL: Exactly. So I would post photos of hand-painted signs on our blog, and I was like, “sign painting!” And these sign painters would say, “That’s not sign painting. That’s a garbage sign. That’s not a representation of our trade.”

My interest is heavily connected to ‘crap signs,’ and I think my aesthetic—as you get older, your aesthetic changes no matter what—my appreciation for different kinds of signs is totally still there. But my education on the process behind them is altered. I mean I’m more likely to shoot a photo of a crazy, wonky bait-and-tackle shop with a weird fish and something misspelled, because that’s what I like. But if I was to put two signs side-by-side and talk about the difference, I can tell you now why they’re both important. Different sign painters will have different opinions on that kind of stuff, but I think a lot of them still appreciate the hilarious, misspelled, ugly-but-sort-of-appealing stuff because it’s funny.

BLVR: A lot of folks might think, you know, a sign. A sign is a sign. Tell me why that distinction matters to sign painters and, presumably, also to you.

FL: A major theme that kept coming up in our interviews was the idea of permanence, and investing in your family. You used to have a family business and it would be passed down, so you’d want your door lettered in gold leaf because it showed that you were going to be there, and you wanted your customers to trust that. Now you have a block with all these flappy vinyl signs, and you don’t know if that business is going to be there next week because they just clip down their vinyl sign and they disappear. There’s no personality in a lot of newer signs. It’s temporary.

(Designed and painted by Ira Coyne)

BLVR: In Sign Painters, Ira Coyne [who designed and painted the book’s cover] says, “Today the things that are made are not meant to last, they’re temporary, but the by-product of that is not temporary at all.” He’s referring specifically to the throwaway nature of the things we make and buy, and the impact of that behavior on our natural environment—

FL: Well and part of what’s happened I think in the last five years is that there’s been a general trend of returning to handmade. Thinking about how you’re spending your money as a business owner and as a consumer. What we saw in a lot of the bigger urban areas was a lot of younger business owners opening up businesses and really investing in the façade and in the permanence of their business. So along with that, there’s this kind of boom in hand paint. But it’s more expensive to do hand painting. It’s not cheaper. And people are really obsessed with what’s going to be the cheapest option. So that’s why when vinyl came along a lot of sign painters just put down their brushes.

BLVR: But so vinyl aside, there are the sort of homespun signs you’ve been documenting for years, and then there’s the work of professional craftspeople.

FL: And now I know the difference. Like for a sign painter, the most successful sign sometimes is one that you don’t even realize you’re reading. Like a NO PARKING sign. Or a sign that tells you to turn left. That’s something I was really schooled on over the last three years, is that a good sign isn’t necessarily…

BLVR: A good sign doesn’t necessarily draw attention to itself at all.

FL: Right. It communicates a message clearly and in a way that you might not even realize that you’re ingesting information. We talked to a sign painter in Cincinnati named Justin Green, who—do you read comics?

BLVR: Some. Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary? Is that him?

FL: Yes! So Justin is actually a really—a lot of the sign painters are also cartoonists. There’s an interesting parallel. So he has a really successful graphic novel career, and he does a comic strip called Sign Game in an industry magazine every month. But also he did music comics for… what was the big record store that closed? It was like a yellow and black…

BLVR: Tower Records.

FL: Tower Records. Tower used to do a monthly music magazine [PULSE!] and Justin used to do a comic in the back about a different musician every month.

So anyway, he took us to a wall in Cincinnati. He was like “I want to meet you on this corner.”We’ve never met him. Okay. And he was standing under this NO PARKING sign in front of a church and he said “this is the best sign in the city.” And it was old; it was probably from the forties. It was on metal. And he explained that you can tell where the sun has hit it because it’s faded on one half. You can see the brush strokes where it’s faded. And you can tell that this was a journeyman sign painter who did a knockout job, really quickly but perfectly, because you could see where his brushstrokes were: he didn’t go back over it. I guess you could call it an “a-ha moment” for me, which is totally embarrassing, but I was like, fuck, I never thought about that. NO PARKING.

BLVR: Do you think traditional sign-painting is coming back?

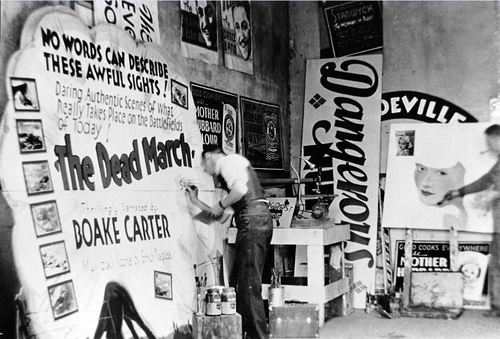

(Sign painter Chancey Curtis working in an unidentified theater, Mankato, MN, ca. 1930s. Credit: Mike Meyer)

FL: It’ll never be what it was. But I think—as a non-sign painter, but someone who has been conscious of lettering and urban landscapes for a long time—the last sign painter is not going to die off in our lifetime. There’s a small but growing amount of people in their twenties and thirties who are learning how to do traditional hand paint.

BLVR: How feasible is a sign painting career these days? How does one go about learning hand lettering?

FL: Well, the last trade school we’ve found that offers a traditional hand painting program is L.A. Trade Tech. They’re the only one that’s open anymore. It’s a two-year program, five days a week, six hours a day. The guy who runs it, Doc Guthrie, is a sign painter. He’s hardcore. If you miss two classes, you get kicked out.

The problem is that our generation wants to learn things really quickly, and it’s not something you learn overnight. It used to be that you’d work at a sign shop as an apprentice and you’d start with a pencil and learn muscle memory, and you’d draw the same line over and over and learn how to do it properly. And then you would grow from there. You don’t just pick up a brush and start lettering. I mean, a lot of people did do that and learn backwards, but there’s a right and a wrong way to do it.

BLVR: When you made Handmade Nation, it was kind of like just picking up a brush and starting to paint. You didn’t really know what you were doing. You paid for the filmwith a bunch of credit cards and a little fundraising. How did you approach The Sign Painter Movie differently?

FL: I did Handmade Nation with no budget, but for this project I got a research grant from The Center for Craft, Creativity and Design. I applied for this research grant and they gifted me the full amount, so we had $15,000 to work with. Which—in the grand scheme of making a feature length documentary—is like pennies, but it really gave us the final push to get stuff done.

This project is totally different for a lot of reasons. The major difference is that Sign Painters is a fifty-fifty collaboration with Sam [Macon], so it’s not the same type of thing where I can just…. I mean, for Handmade Nation we did a lot of interviews with no idea of what we were going to do with those interviews. My editor [Cris Siqueira] would tell me, “Have a plan before you start shooting,” and I was like,“I just need to start interviewing these people.” I didn’t go to film school. I’m not thinking so much about the narrative arc. I’m thinking there’s really important information here, and somehow it’s going to get ingested. But working with Sam has been really valuable for me. Sam’s a filmmaker. He does a lot of commercial work, but we’ve collaborated a lot, so I knew working with him would help me stay on track.

Handmade Nation was an anomaly. I was able to make it really successful without doing anything in the correct, traditional way. I handled all of my own booking, all of my screenings. It was not a festival film; it didn’t get into any of the festivals that I applied to. It was invited to festivals afterward, but it was never sold; I retain the rights. The Sign Painter Movie will have a proper festival release, and hopefully it will be picked up by a distributor and we’ll sell it.

BLVR: It’s still in post-production. You already know it’s going to be picked up by a festival?

FL: No, but that’s the ideal. And it should. It’ll have a festival premiere, a distributor will be interested, and then we sell it. And then what happens is you don’t retain the rights; your distributor handles it. I don’t totally understand how that works. If someone wants to have a screening, the logistics will be different—which is fine, because I don’t think I could physically or mentally handle the travel that I did for Handmade Nation, where I basically took every opportunity that I was offered. I mean I basically traveled three-fourths of the year for two years straight. It was really taxing. I think it was really valuable, but not for my sanity.

BLVR: Handmade Nation documented mostly younger people—crafters and entrepreneurs, mostly women. More often than not, the sign painters are men, they tend to be older. Theirs is a ‘proper trade.’ What do you think connects this project to the last?

FL: The sign paintersproject is just an extension of everything I do. Handmade Nation wasn’t necessarily spawned out of my love of craft; it was more just: think about what you’re buying, why you’re buying it, what you’re looking at, what’s interesting about it to you, and how you ingest the information around you.

In general, I’d like to think that all of my work makes people think about their surroundings. I’ve always been really interested in marketing and advertisement and consumerism, and sign painting is at the absolute root of that. I mean you paint a sign, you want your customer to see it, to recognize it, and to come in and buy your product. Getting someone’s attention, getting them in the door, getting them to pull their wallet out. And I really feel like Sign Painters is going to create a conversation—a foundation for a bigger discussion about visual culture and urban landscapes. At least I’m hoping that’s what it’ll do.

BLVR: What’s the age range of the folks you met and interviewed for this project?

FL: I think 29 to 92.

BLVR: There’s a nice symmetry to that.

FL: The average age of the older generation of folks we interviewed was in their sixties, and most had 20 years of sign painting behind them. In our generation, I don’t think that most of us, when we’re in our sixties, will say we did the same thing for even ten years. I mean I’ve been self-employed for eight years, but through those eight years I’ve had a hundred and one different job titles. But if you’re in your sixties and for thirty years of your life you did one trade and then it was pulled out from under your feet— I get emails daily from sign painters who hear about this film and they either want to be interviewed or they’re just saying thank you for bringing attention to our trade. A lot of sign painters feel like they have never gotten credit for what they’ve done because no one thinks about the sign, even though everyone looks at signs all the time.

BLVR: I keep thinking about that old Sesame Street thing, The Mad Painter, who would go around painting the number nine or whatever all over town. And how cool it was just to watch that happen even though it was so no-frills.

FL: When you watch a sign painter put their brush to a surface and knock out letters, it’s almost like watching a Disney film where there’s a magician waving a wand, or like Mary Poppins sort of, like holy shit!

I’ve been with different painters doing a wall or a window in public, and people come up and ask, “What are you doing?” and the painter will say, “I’m painting a sign.” And they’re like, “You’re just—you’re doing that?!” And I want to say, “What’s wrong with you? He’s obviously doing it; he has the brush in his hand.” But people are so disconnected from hand-to-material process. I think what’s really exciting about this project is that it’s a reminder—but also maybe an education—for people to see that if they focus on something enough, they are capable of making amazing things happen.