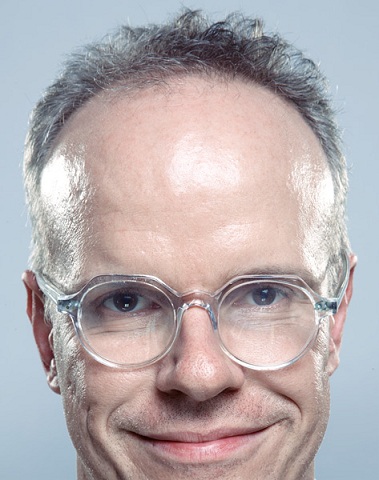

An Interview with Hans-Ulrich Obrist [curator]

Part I.

Published in the current issue (no. 5) of The White Review

photo by Nick Wilson

Hans-Ulrich Obrist is a compulsive note taker. For the duration of our interview one hand twitches a pen across a scrap of paper before him on the table, while the other frenetically twists it clockwise and anticlockwise against the horizontal. The extent of twitching and twisting increases in direct equivalence to Obrist’s mounting exhilaration at the development of a scheme of thought, becoming most frenzied when patterns emerge, when one idea reveals its correspondence with another. On those not infrequent occasions that Obrist’s hands are called up to add gestural emphasis to his speech I am allowed a glimpse of the leaf of paper, which over the course of our time together becomes clogged with intersecting lines, marks, scrabbles and symbols, like an elementary geometry lesson rendered by Cy Twombly.

This cryptic log of our meeting is symptomatic of the mania to record and preserve that has led Hans Ulrich Obrist, the pre-eminent curator of his generation, to record hundreds of interviews with the world’s most significant artists, scientists, writers, architects, philosophers and filmmakers over the past twenty years. A casual cross-reference of The White Review’s all-time fantasy list of interviewees against Obrist’s résumé has these names, among others, in common: Czesław Miłosz; Michel Houllebecq; Merce Cunningham; Benoît Mandelbrot; Marina Abramović; J.G. Ballard; Gerhard Richter; John Baldessari; Eric Hobsbawm; Ai Weiwei; Studs Terkel; Doris Lessing; Edouard Glissant. Which makes the prospect of interviewing him quite nerve-wracking, even before he starts taking notes.

It is, nonetheless, for his work as a curator of exhibitions that Obrist is most widely revered. He held his first show in his kitchen in 1991 at the age of 23, famously convincing Christian Boltanski and Hans-Peter Feldmann to contribute site-specific installations. In 1993 he founded the Museum Robert Walser and began work as a curator at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, since when he has organised over 250 exhibitions across the world. He became famous for his promotion of an open-ended curatorial practice that prioritises participation and flexibility. Do it, a project he inaugurated in 1997, perfectly exemplifies his preoccupations. Consisting of a set of artist’s instructions, the touring exhibition allowed for those directives to be interpreted differently at each venue that it visited, creating a model of curation that encourages diversity and freedom. In 2006 he joined the Serpentine Gallery, London, as co-director of exhibitions and programmes with Julia Peyton-Jones, and in 2009 he was named by ArtReview as the most powerful person in the art world.

We met at Obrist’s office near the Serpentine Gallery, in west London, at the relatively civilised hour of 9am (the curator is notorious for his Brutally Early Breakfast Club – a roving salon that commences at 6.30am). We drank more coffee than can be healthy over the course of a morning in which I was able to experience first-hand the infectiousness of Obrist’s energy and enthusiasm, as well as his ability to fit more words into a minute than one would think possible. – Ben Eastham

THE WHITE REVIEW: Do you remember your first encounter with art?

HANS-ULRICH OBRIST: I started to be very interested in art was when I was ten or eleven. It was during this time, up to the age of fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, that my visiting museums became quite compulsive. I started to buy lots of books, and I went to see Giacometti again and again at the Kunsthaus in Zurich. These very thin, long figures of Giacometti were kind of a trigger to my interest in art.

Then at some point there emerged a desire, a necessity, to meet artists. When I was sixteen or seventeen I made a studio visit to a Swiss artist in Lucerne and it was an incredibly exciting thing, the most exciting thing I had experienced up to then in my life. I started to ring up more artists and to make more studio visits. And it was really in ‘85, when I was seventeen, that I think I was born a second time in Zurich, in the studio of [Peter] Fischli & [David] Weiss. It was a special moment because Fischli/Weiss were doing the film Der Lauf der Dinge [‘The Way Things Go’], one of the great artworks of the second part of the twentieth century. For me as a kid to come to a studio… It was just so fascinating that I thought, ‘that’s what I want to do with the rest of my life’. I wanted to work with artists and be useful, to be a utility for artists.

By the time I left the Lycée it was all clear, I knew I wanted to become a curator. I had met Alighiero Boetti when I was eighteen and that was another sort of epiphany, as was meeting Gerhard Richter. Richard Wentworth was a huge inspiration to me as to so many artists. My being so young opened a lot of doors, because it seemed so ridiculous [to the artists], this teenager obsessed with art.

TWR: But you continued on to university, where you studied Sociology and Politics? Was it a deliberate decision to read something at least superficially unrelated to the arts?

HUO: I didn’t really know where to start as a curator, because I had this feeling that everything had been done. So I thought that if I was to be very clear about it, and also to calm my parents, I should go to university. At the same time I also wanted to study a subject I would never do autodidactically, as I would do with art. Because I never had the courage to just read books on economy and on social science, and I wanted to understand the world.

TWR: Have you always felt compelled to try and make sense of the world?

HUO: In some way I think it dates back to an experience I had as an eight-year-old kid, when I first visited the famous Abbey Library at Saint Gall, in Switzerland. You had to put on these felt shoes to enter the library, almost like a Joseph Beuys installation, and they would give you white gloves to look at the medieval books. I was fascinated by the idea that these monks wanted to know everything. It was at least theoretically possible in the Middle Ages to know everything that was known, whereas now we live in a very specialised society, with an abundance of information, in which none of us could know everything.

TWR: You talk about yourself as an autodidact, at least in relation to art, but there’s this compulsion as well to broaden out the sphere of what art constitutes. I wonder if the Interview Project is a means of continuing that education, allowing you to learn from people in different disciplines. How does that relate to your attitudes as a curator and your engagement with the art world more generally?

HUO: When I started I would always talk to artists, and talk to artists, and my life became this infinite conversation. Whenever I had time I would go to studios, go to openings, and have these conversations, infinite conversations… All my exhibitions grew out of these conversations, starting with Kitchen Show [in 1991] and including things like the Monastery Library [of Christian Boltanski in the library at Saint Gall], my show with Gerhard Richter in the Nietzsche House, the exhibition on an airplane with Boetti, an exhibition in my hotel room when I arrived in Paris in 1993. I invited everyone to my hotel room and showed them around. Strange exhibitions in unusual locations. All of these things came out of conversation with artists.

I realised that all these conversations were being lost, because I only took notes. When Boetti died, it was a watershed moment. I realised we had had so many conversations, and I had lost a lot of that. My memory is not perfect. Recording conversations became a protest against forgetting. I wanted to have traces.