Idol Threats

October 1st, 2021 | Issue one hundred thirty-seven

A citizen sleuth is tracking down India’s stolen artifacts—but what happens to the idols once they’re home?

Early one Saturday morning in the summer of 2013, Vijay Kumar, a shipping executive in Singapore, woke up to a news alert on his phone. A museum in Australia had, after protracted prodding and delays, finally disclosed how it came to possess an ancient Indian relic with a suspicious history. Kumar was eager to see what it had been so reluctant to reveal.

Kumar is a self-taught expert on Indian antiquities, traveling frequently to temples in his home state, Tamil Nadu, to document the sacred treasures they contain. He traces his interest to a trip he took to a South Indian temple, where he overheard a father misidentifying a god to his son. This both outraged and inspired him to write a blog on ritual art called Poetry in Stone as a kind of “dummy’s guide” to ancient Hindu and Buddhist art and iconography.

On expeditions over the previous decade, Kumar had noticed many empty niches where statues once stood, and had peered at divinities through padlocked iron grilles. Theft of Indian idols for sale to overseas museums was rampant. The Australian news report seemed to describe one such case.

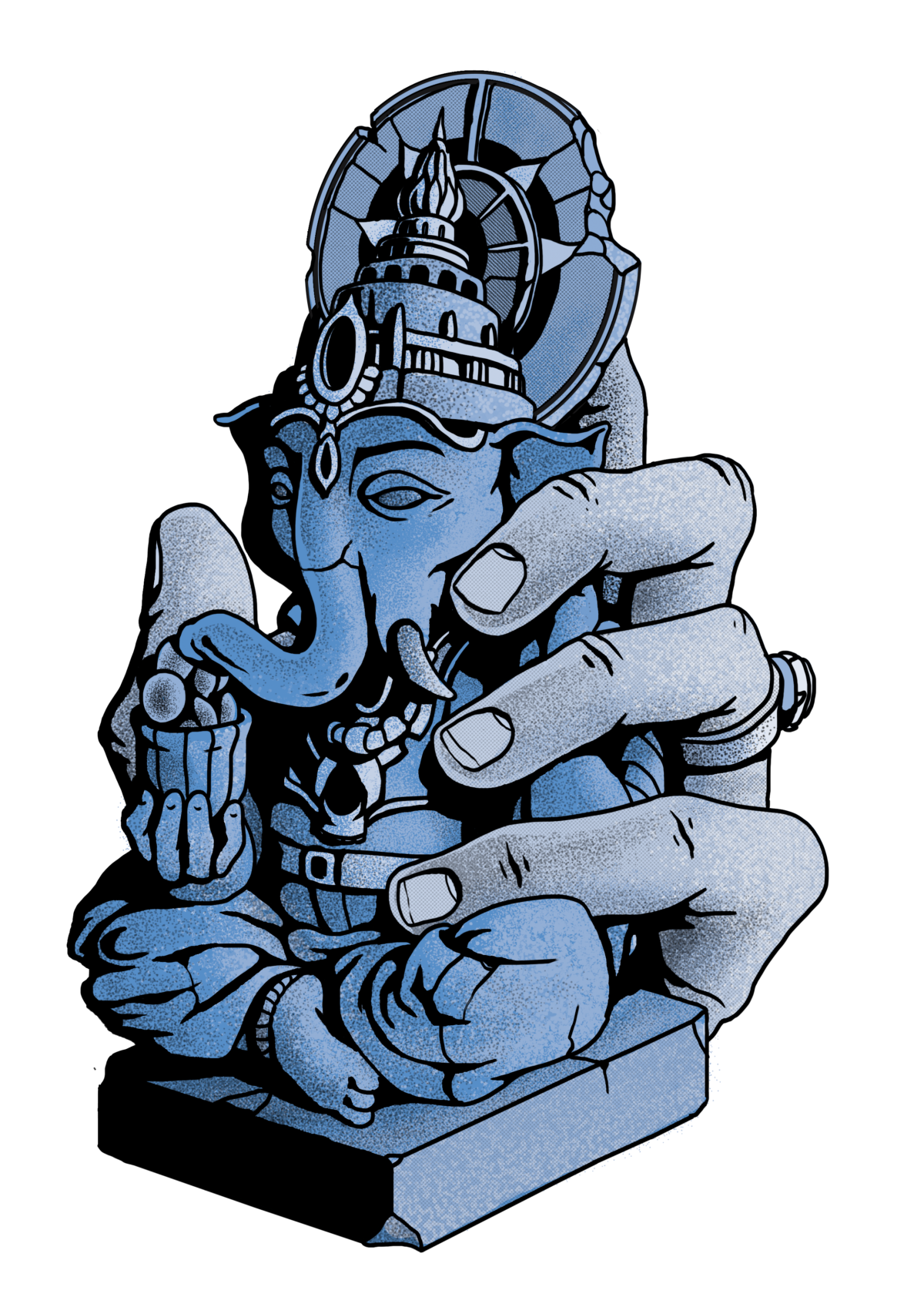

As Kumar read the details of the report, a particular image surfaced in his mind. The statue under investigation was described as an androgynous divinity. As it happened, Kumar had recently written a blog post about the androgynous avatar of the god Shiva—the Ardhanarishvara, or “the Lord who is half woman.” As an illustration, he had used an image of an early medieval sculpture in a temple in Tamil Nadu. Carved from granite darkened by a thousand years of ceremonial smoke and incense, the statue depicted the beatifically smiling god with his matted hair piled in the shape of a crown. Kumar was transfixed by the way the languid curves of the deity’s female side were counterbalanced by his taut male side, which reposed on a stately bull. The statue’s astonishing beauty, though, was marred by damage: both its hands had been lopped off.

Sensing a connection, Kumar dug further and unearthed a photo of the statue in Australia—it also had missing hands. But as far as Kumar knew, the original sculpture was being worshipped in a temple in South India. He wrote to the journalist whose name was mentioned in the article, asking for more-detailed photographs. A closer look confirmed it was the same sculpture. “That’s when I realized I was onto something,” he says.

He needed more than his own eyes to convince authorities that the statue was stolen, however, so he logged on and asked his two thousand Facebook followers if any of them could go to a temple in Virudhachalam village and pay the statue a visit. Within minutes, he heard back from an engineer in Dubai whose friend ran a cell phone repair shop in the village. The friend went to the temple and sent back photos of the niche, where a suspiciously glossy statue with two intact hands now resided. “It was a modern fake,” Kumar says.

Kumar’s discovery added to mounting evidence against Subhash Kapoor, a New York City art dealer who owned an Upper East Side gallery called Art of the Past. Over three decades, Kapoor had sold thousands of antiquities to museums in Europe, Australia, and North America. Of these, his neighbor the Metropolitan Museum of Art had bought at least fifteen. But Art of the Past was a front. Its real business was conducted far from Museum Mile, in West Nyack, New York, through a company called Nimbus Import Export. A federal investigation found that the business amounted to “a black-market Sotheby’s,” its wares supplied by temple raids that Kapoor commissioned. The spoils found their way to buyers, curators, dealers, and private collectors via a browsable photo gallery. “Like prospective grooms looking for matches, these guys were picking and choosing the best of ancient Indian art,” Kumar says.

Kumar’s confirmation that the androgynous idol had been stolen cranked bureaucratic wheels into motion, the return of the sculpture was requested by the Tamil Nadu Police, and the androgynous god was at last sent home on a private jet. “A journalist contacted me to let me know when he was in the air,” Kumar says. “I was ecstatic to hear he was coming home.”

Over the past few decades, countries with ubiquitous but poorly secured temples and museums, like India, have proven easy targets for smugglers. The extent of the theft is enormous, but exact figures are hard to come by; about 5.7 million of India’s 7 million antiquities are undocumented. A scathing 2013 report by the country’s government watchdog blamed the custodian of national antiquities for not bothering to maintain a record of what it possesses. An estimated—likely underestimated—4,408 relics were stolen from sites under this organization’s less than watchful eye over a recent four-year span. Such losses are nothing new; UNESCO estimates that prior to 1989, about 50,000 antiquities were removed from the subcontinent.

India is not especially spirited in the pursuit of its lost treasures, compared with countries like Italy, Greece, and China. Italy has a police wing dedicated to combating theft and the trafficking of cultural artifacts and maintains a database of stolen relics. Greece wages tireless and aggressive campaigns to recover its relics from numerous countries, including the United Kingdom, which refuses to relinquish its hold on the Parthenon marbles it took when Greece was under Ottoman occupation. And China has a state-run program that dispatches delegations to scour the archives of international museums for mislaid relics. The Indian government, meanwhile, has rarely pursued lost antiquities.

In some places, ordinary citizens have filled in for their governments in demanding the repatriation of their countries’ art. Mwazulu Diyabanza, a Congolese activist, was arrested and charged with theft last year for seizing a Chadian funerary post from an anthropological museum in Paris. Likewise, in China, a group of unidentified bandits have organized over the past two decades to extract Chinese antiquities from a smattering of European museums and royal residences.

And since 2014, India has had Kumar. The retrieval of the androgynous god marked the beginning of his career as a stolen-artifacts hunter. After the case, he became increasingly convinced that his profession, in transnational shipping, was implicated in the frittering away of these treasures. One-ton bronze statues couldn’t be tucked in a purse or stowed in airplane baggage. These statues were being transported by sea. Kumar decided to use his knowledge of global logistics to sniff out fraud in the paperwork.

He believes his efforts to catch smugglers have been more successful than those of any government agency in India: Kumar estimates his work has led to the majority of the fifty-one restitutions that have occurred in the country over the past eight years. His only compatriot in the field—a retired archeology professor named Kirit Mankodi, whom he sometimes collaborates with—has helped recover far fewer, just two antiquities around the same time frame.

The commitment of Kumar and other amateur sleuths is laudable, but their activities have also brought some uneasy legal and ethical questions to light. In the case of relatively recent thefts, like the handless relic, repatriation is the obvious course of action. But what about art that was spirited out of a country not a year ago but a century ago? Do people who have never officially possessed it have the right to demand it back? And if, once returned, the art is forsaken, who is responsible then?

To Kumar, the experience of repatriating the androgynous god was exhilarating but sobering. It demonstrated to him that without his intervention, India’s divinities would continue to be stranded abroad. He thought of Vaman Ghiya, an art dealer who funneled some twenty thousand antiquities out of the country before being arrested, in 2003. It enraged him to think of the bureaucratic lethargy that has caused countless sacred relics to remain dispersed throughout the world, despite easily locatable proof that they were acquired by questionable means. So, to complement his work as a repatriation hobbyist, he decided to conscript a lobbyist. Along with his colleague Anuraag Saxena, a former investment banker based in Singapore, and dozens of like-minded nationalists, Kumar formed the India Pride Project, in 2014, with the stated mission of “bringing our gods home.”

The group has two aims. One half of the crew, led by Saxena, leads awareness-raising campaigns intended to prick the conscience of—in his words—“societies that have normalized kleptomania.” They organize protests outside museums that have collections of ancient Indian art in London and North America and make impassioned speeches to promote their cause. In a protest in 2018, Saxena and a handful of demonstrators went to the British Museum and photographed around twenty relics of Indian origin, with speech bubbles held up next to them: help!!! the brits have kidnapped me!; i’ve been snatched, sold, paraded, and shamed; and ask yourself: how did I get here?

Kumar’s group is the black-ops branch of the movement. He leads a posse of volunteers who pose as prospective buyers of antiquities at auctions in Amsterdam, London, and New York, then send him pictures of potentially repatriable antiquities. (“I’m like Nick Fury, and they’re my Avengers,” Kumar says.) He prints out the photos and splays them across his bedroom wall in the style of a TV detective, until his wife tears them down. He stares at them for hours to see if any of the objects spark recognition. When one does, he searches for a matching photograph or other record of the object in its country of origin. If what he finds amounts to robust evidence to demand the object’s restitution, he sends that evidence to Indian diplomats posted in the country where the relic surfaced, in coordination with antiquities authorities in New Delhi.

The press often likens Kumar to Indiana Jones, but he sees himself more like Robert Langdon, the symbologist hero of The Da Vinci Code. “We’re both unfit,” he says with a laugh. “We’ve both got a great memory: he recollects passages, I recollect images.” Kumar claims to have crammed his mental database with the contents of out-of-print art history books, which he slots according to a mental algorithm that moves from style to region to period to dynasty. Mentally filing away references helps him spot telltale correspondences between those references and objects that surface in auctions or museums. A blemish on a nose, a crack in a carved leaf. “It’s like a game to me,” says Kumar. “Other people play UNO; I play with idols.”

Eidetic tricks aside, Kumar thinks the most striking similarity between himself and Dan Brown’s hero is that they’re both solitary figures facing off against a powerful, shadowy conspiratorial cabal. “Both Langdon and I are not scared to take on the big mafia,” he says. “The only difference is that I do it without government support. And I deal with lots of red tape.”

Demands for repatriation are far from a recent phenomenon. They date back as early as 1936, when the oba of Benin requested the return of ritual objects seized by British troops in their violent invasion and sacking of Benin City, in present-day Nigeria, in 1897. Repatriation requests rose in the ’60s and ’70s, when African states won independence. But the sorts of anthropological and “encyclopedic” institutions that amassed colonial-era loot—and the former imperial powers to which they belonged—long found it expedient to evade such demands. When the landmark UNESCO convention prohibiting the illicit trade in cultural property was passed in 1970, many countries including Britain tarried for decades before ratifying it. For the most part, Western museums operated under a philosophy popularly encapsulated as “What’s mine is mine; what’s yours is mine.” This approach was exemplified by the 2002 “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums,” a statement put forth by the directors of the British Museum, the Louvre, the Prado, and fifteen other institutions to preempt repatriation claims. In the declaration, the directors emphasized the role of Western museums in inspiring the “universal admiration” for the ancient civilizations whose treasures they displayed. They exhorted their audience to “acknowledge that museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation” and argued that whittling down their “diverse and multifaceted” collections through repatriation requests, however legitimate, “would therefore be a disservice to all visitors.”

In recent years, however, the clamor for repatriation has grown into something of an international movement, borne by powerful political and intellectual currents that challenge the stories these museums tell the public about themselves. To repatriation advocates, museums are not neutral storage containers that just innocently happened upon the treasures they possess. Rather, they were purposefully built by imperial powers to advertise and justify white supremacy, by juxtaposing “superior” Western art and archeology with the plundered relics of cultures and societies they subjugated and destroyed, and whose peoples’ skulls they pseudoscientifically displayed as “primitive.” “As the border is to the nation state so the museum is to empire,” writes the archeologist and curator Dan Hicks in his book The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. The solution he and his fellow advocates propose emphasizes “acts of transparency,” starting with the restitution of ancestral cultural objects that were expropriated during colonial times. They point out that many of these objects were obtained through theft, violence, or duplicity, and assert that holding on to them would deprive formerly colonized people, including indigenous populations, of their living heritage, which forms a part of their identity. In 2018, the movement gained its biggest victory thus far in the form of a landmark report commissioned by French president Emmanuel Macron. The report pointed out that over 90 percent of Africa’s cultural treasures were found outside that continent, and recommended, as a corrective measure, nothing short of the swift and permanent restitution of thousands of artifacts acquired during France’s colonial era. Two other former imperial powers, the Netherlands and Germany, were also galvanized into similar action.

Faced with increasing demands for radical action, directors at the largest museums in the world envision a

“horror scenario”: their rooms and storerooms emptying out overnight. To them, repatriation represents a kind of lawful robbery. They view it as an existential threat, one that could threaten their livelihoods and the objects they’ve studied and safeguarded throughout their professional lives. Neither are they convinced that repatriation is entirely justifiable. As they see it, since there is no clear “cultural continuity” between the ancient Athenians and the present-day Greeks and no traceable direct descendants of Sumerian or Assyrian kings, Western museums are equally entitled to the relics these long-dead people left behind. Further, they argue that repatriation advocates tar all objects acquired in the colonial era with the same brush, adding that many treasures were gifted or willingly shared with colonial officers or missionaries. Finally, they say that not repatriating might often be in the interest of the relics themselves; as the first indigenous director of Paris’s Musée du Quai Branly put it in a 2020 interview with The New York Times: “I’m not in favor of objects being sent out into the world and left to rot.”

Whichever side of the debate you are on, one thing is certain. The fate of all antiquities, whether in the custody of museums, dealers, or auction houses, boils down to one arcane detail: their “provenance,” or the paper trail that documents their history of ownership. These details, or the absence of them, can establish whether a relic is repatriable—if it left the source country after 1970, when the UNESCO Convention prohibiting the export of cultural property was passed, or may have been unlawfully seized from its owners. A clear, uncomplicated provenance can also bolster the case for a museum that wishes to hold on to an object. The problem, however, is that only a tiny percentage of antiquities currently residing in museums or surfacing in the art market have a well-researched ownership history.

The reasons for this depend on whom you ask. For Kumar, it’s a willful obfuscation, an exploitation of a shoddy system by smugglers and the curators whose collections ultimately reap the benefits. “In most cases,” he says of the museums, “they knew it wasn’t an innocent good-faith purchase. They knew it was fresh plunder, fresh loot.” Victoria Reed, curator of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has a less nefarious explanation: provenance is expensive to research, and it’s a relatively recent field that came into existence in the late ’90s when a number of cases brought to light art objects that had been illegally expropriated, including those by the Nazi regime during World War II. Prior to that, the acquisition process relied on a “kind of gentleman’s agreement atmosphere,” Reed says, “that you know the dealer, trust the dealer, the dealer will give us a good object, and if it has an ‘interesting’ history, we will ask about provenance.”

Still, it is undeniable, and widely acknowledged, that many of these documents are entirely fictive, serving only to legitimize artifacts in the service of museum curators and private collectors.

Erin Thompson, an archeologist who researches art crime, says the vast majority of antiquities present an intractable challenge for provenance researchers: they’re often from underdeveloped source countries where the circumstances under which they were excavated and owned are unknown or unknowable. The lack of information increases the chances that museums might unwittingly acquire fakes and also lose information on the place and time an object was disinterred or created. “We’re so concerned about holding on to these collections,” Thompson says, “that we’ve crushed the usefulness out of them.”

Sometimes, staring at the photos on his wall, Kumar imagines himself alone, facing off against an assemblage of adversaries, composed of robbers, shady dealers, and corrupt connoisseurs. If any one person comes close to incarnating that shadowy enemy, it would be Pratapaditya Pal, a scholar and curator who built the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s extensive collection of Southeast Asian art. Pal has worked for more than four decades as an adviser to numerous private collectors, including the canned-food mogul Norton Simon, who in 1976 reached an out-of-court settlement with the Indian government over a tenth-century Chola bronze of Nataraja—the deity Shiva’s dancing form—that had gone missing from a South Indian temple two decades earlier. Simon notoriously told The New York Times, “Hell, yes, it was smuggled. I spent between $15 million and $16 million in the last two years on Asian art, and most of it was smuggled.”

I talked to Pal over the phone, after a lengthy correspondence, during which he scrutinized my CV and a number of writing samples and attempted to dissuade me from speaking with him. When we did speak, however, he shared his views with few reservations: “I am strongly opposed to the idea of repatriating art in general,” he said. “This issue is becoming as absurd as that of abortion in the United States. We want to save the unborn child only to shoot them down mercilessly at schools or send them off to useless wars in their youth to die.” He was gratified to see sacred Indian art well preserved and well displayed in museums in the global North, where, he said, they serve as “the silent ambassadors of the country.” Repatriation, he believed, would doom these works to an ignominious fate. “Have you been to the oldest museum in Asia?” he said. “It’s in Calcutta. Forget about the display, which is disgraceful, but if you wanted to see the thousands of objects in their storage, you’d have to take a sweeper along with you to dust the sculptures, or you won’t see anything!” Of the repatriated objects, he asked: “Where will they put them?”

Pal strikes an almost defiantly anachronistic position in the antiquities world. He has spent his retirement writing a number of nostalgic essays chronicling a lifetime spent socializing over whiskeys with “pucca gentlemen” collectors with deep pockets and a self-cultivated taste for ancient Indian art. He celebrates the “extraordinary omnium gatherum” of ritual Indian art that crowded the darkened recesses of his aristocratic friends’ Upper East Side townhouses.

Pal’s insouciant persona seems designed to revolt Kumar. As he sees it, the work of curators like Pal, in helping museums in wealthier countries amass relics that go on to be preserved, studied, and admired, is not a worthy contribution. It does not, he thinks, signal their respect for sacred objects. In fact, as he sees it, it is a distinct lack of respect for “our gods” that permits curators to put them on display in galleries and museums, where supposedly admiring guests gather around them and pose with them, champagne coupes in hand. “To me, it is defilement,” he says. A Nataraja ought not be reduced to “a showpiece curio,” he says, adding: “A Nataraja does not want a focus light. Nor does he want a temperature-

controlled environment.” His exasperation then mellowed into reverie. “In my ancestral village,” he says, “I’ve seen an old priest running from his home to the temple with a bowl of rice, fearing that God is going hungry.” Every day, Kumar says, this priest rouses the Lord from sleep, bathes him “like his own child,” dries him, and dresses him up in silk, flowers, and diamond necklaces. “Once you’ve seen that,” he adds, “you would never want him to be displayed in the nude, with no rituals.”

Kumar’s distaste for men like Pal is palpable. But I’m struck by what the two have in common: both are drawn into a bit of a feeding frenzy at the prospect of acquiring these divinities, whether on behalf of a country or institution; both share tales of tireless, near-obsessive pursuit; and both are fond of rhapsodizing about the beauty of the relics they pursue. And both are proud of their hard work, accumulated expertise, and fierce commitment to their diametrically opposed missions.

Since Kumar’s favorite androgynous relic with the lopped-off hands made it back to its place of “birth,” many more smuggled sculptures have been repatriated to India. In Tamil Nadu, an obscure police department known as the Idol Wing has been confiscating hundreds of sculptures from private collectors and museums across the country. Kumar considers all returns positive, whether they’re from abroad or from elsewhere in India. As he sees it, the icons are now back where they belong. But where is that, exactly? Pal, the curator, conjured for me a glum vision from the first Indiana Jones film, when the Ark of the Covenant gets shunted into a shabby crate that floats out into a sea of other shabby crates. “They’re probably rotting in a storeroom somewhere,” he says, “just like the bronze Nataraja that our poor country spent millions of dollars in legal fees to bring back in 1986. It was a cause célèbre, but today you can’t see it anywhere.”

I decided to pay a visit to the androgynous Shiva to see how it was faring. It had spent the past five years at an “icon center,” a shelter for repatriated relics, housed at a temple in Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu. One afternoon in August 2019, I entered the temple’s towering pylon-like entryway, which featured brightly painted stucco gods seated on cows, rats, and peacocks, and surrounded by romping demiurges, sages, and princes. A soulful Tamil movie tune wafted out of a nearby tire shop, and a flower seller by the entrance dozed over a soft pile of jasmine and rose garlands.

I crossed a sunlit courtyard and asked a passing priest where the temple’s administrative office was, and he waved me toward a tiny room, where a few functionaries were sipping filter coffee. When I asked to see the androgynous relic, one of them, an accountant, shook his head vehemently. He informed me that the idol was “undergoing a court case” and was therefore barred from view. “So no one can visit?” “It’s a prohibited area, not a museum,” he replied, adding that “general people” were not allowed in. “How about art scholars?” “No probability. No chance,” he said.

In hopes of getting a glimpse nevertheless, I walked to the building where the relic was held. It was low-slung, painted petroleum green, and resembled a bank vault. The entrance consisted of a retractable security grille fortified with two padlocks, behind which was a heavy door with a heftier padlock. Twice a week, the building is opened by a security guard, and a priest and two accountants armed with mops and brooms are allowed entry. The three get unimpeded access to more than a hundred repatriated relics, unclothed due to risk of fire, inside the icon center’s air-conditioned rooms. While the accountants mop the room and dust the shelves, the priest performs an abbreviated ceremony—without lamps, oils, or ash—in the general direction of the statues. “It’s just for ritual purpose,” one of the accountants told me. “Not to see, not to touch.”

I left without seeing any of the idols, and not quite knowing how to feel. It seemed a sorry fate for sculptures that were once on public display, admired and revered by thousands. I saw the case for a middle ground, one wherein relics that are culturally and religiously meaningful are returned with the promise of custodians to adequately preserve them, and other relics are left in place, where they are appreciated, instead of vanishing into an oversize walk-in closet.

A few months after my visit, in November, I read about a thousand confiscated wooden and stone relics that had been tossed into the backyard of the Idol Wing’s branch in Chennai. Temple chariots were piled next to stone sculptures of nymphs and gods, and all had been rinsed by several monsoons and exposed to bird droppings. These objects seemed caught between lives. Once ritual objects, they had transitioned, by theft or gray market transactions, to become valuable commodities. They were then displayed—for clinical study or aesthetic pleasure—in a collector’s home or museum. The act of seizure, however legal, caused a perturbation in their status. They are ritual objects haunted by their time spent as commodities; they can no longer be on open display.

Kumar doesn’t find the fate of these relics so dispiriting. He hopes they will soon find their way back to the temples they came from, but in the meantime, he considers them just fine in a dismal backyard. “What difference does it make? They’re not better off in a rich man’s bedroom in Europe,” he says. “Besides, these sculptures survived four hundred years of Islamic invasions. Their thousand-

year lineage was broken only by greed. Still, they survived. They will survive forever.”