DON’T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD

The door swung open and there she was: Nina Simone, alone in her dressing room, sweat cascading down her shaved head, a wig thrown to the floor and two glittering fake eyelashes mashed unceremoniously against the mirror.

It was after midnight and the compact and muscular woman radiated anger following a performance at the smoke-filled Village Gate in New York City. “She was scary, for sure,” recounts playwright Sam Shepard, who during the summer of 1964 was a twenty-one-year-old busboy tasked with delivering ice to chill Simone’s champagne.

Only moments before, her long fingers arched over a black Steinway, Simone held the audience rapt, even terrified. “Mississippi Goddam,” her first bona fide protest song, had caused ripples across the country, especially in the South, which was roiling with racial unrest. And in her version of “Pirate Jenny,” the Bertolt Brecht–Kurt Weill song about a beleaguered hotel maid who vows revenge when a pirate ship returns to liberate her, Simone added a biting pathos all her own.

And they’re chainin’ up people

And they’re bring’em to me

Askin’ me, “Kill them now, or later?”

Askin’ me!

“Kill them now, or later?”

[…]

And in that quiet of death

I’ll say, “Right now… RIGHT NOW!”

“It was absolutely devastating to watch,” says Shepard. “It was a real performance as well as just being something heard.”

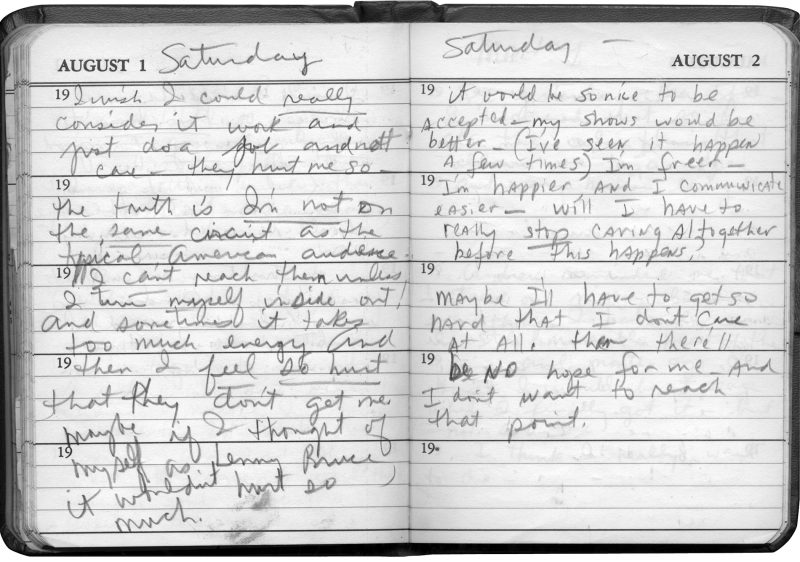

During the riveting and historic concerts Shepard witnessed that summer, Simone was herself devastated, descending into a terrible darkness. “Must take sleeping pills to sleep + yellow pills to go onstage,” she wrote in July 1964, referring to Valium. “Terribly tired and realize no one can help me—I am utterly miserable, completely, miserably, frighteningly alone.”

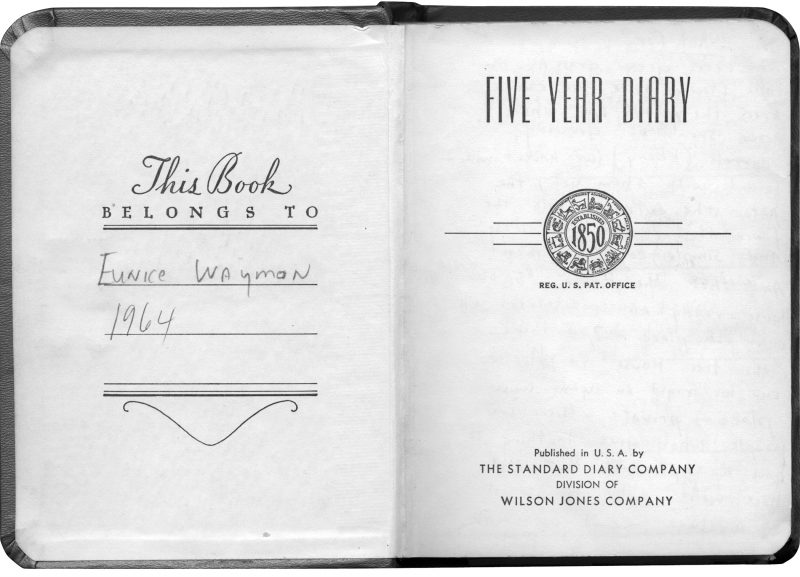

Every night after her shows that summer, Simone drove home to Mount Vernon, New York, a leafy suburb of Manhattan where prominent blacks were living at the time, including Malcolm X. There, unknown to anyone save her husband, she kept a small, leather-bound diary, inscribed, “This book belongs to Eunice Waymon,” Simone’s given name growing up in rural North Carolina. While she electrified audiences in Greenwich Village that night, a musical icon in the making, she struggled privately with mental illness, likely bipolar disorder. In the 1960s, that diagnosis didn’t exist, so Simone was left to manage her erratic moods in any way she could: psychoanalysis, hypnosis, drugs, sex, and, ultimately, writing.

“Now we have names for that shit,” says Shepard. “Back then nobody had names for it,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in