NOTE TO THE READER

This article is divided into two parts: a manual and a scenario. The first part, the manual, is an exposition of the game Dungeons & Dragons: what it is, how it’s played, how it came to be, and how it came to be popular, at least, in certain circles. If you once played D&D yourself (no need to admit that you played a lot, or that you still play), you may want to skim the manual, or turn directly to the scenario, which is an account of a trip my friend Wayne and I took last spring to Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, in order to fulfill a wild and uncool dream: to play D&D with E. Gary Gygax, the man who invented the game (more or less: see below). If it isn’t immediately clear why this would be an interesting, or, to be frank, a fantastically exciting and at the same time a curiously sad thing to do: well then, you’d better start with the manual.

THE MANUAL

1.0 OUTSIDE THE CAVE

You are standing outside the entrance to a dark and gloomy cave. If you are anything like me, you have been here many, many times before. It isn’t always the same cave: Once it was a “cave-like opening, somewhat obscured by vegetation,” which led to the mystical Caverns of Quasqueton; another time it was the Wizard’s Mouth, a fissure in the side of an active volcano (“This cave actually seems to breathe, exhaling a cloud of steam and then slowly inhaling, like a man breathing on a cold day”). Once it was a passage from the throne room of Snurre, the Fire Giant King, “extending endlessly under the earth.” Once, memorably, the “cave” was made of metal: it was the outer airlock of a spaceship which had crash-landed in the crags of the Barrier Peaks.1 You don’t know what lies in that darkness, but you have heard rumors: there are troglodytes, dark elves, a long-dead wizard, terrible creatures, treasure. You are here to learn the truth. So strike a light: you’re going in.

If you are not between the ages of eighteen and forty-five, or if you happen to be a woman, you may not know what Dungeons & Dragons is, exactly, or why you would want to get involved with it, even in the context of an essay in a respectable magazine such as this one. This introduction is for you, although, as it turns out, neither question is easy to answer from outside the cave. TSR Hobbies, the company that used to make D&D,2 once wrote a brochure for hobby-store owners, in which they tried to explain what they were selling:

While one of the participants creates the whole world in which the adventures are to take place, the balance of the players—as few as two or as many as a dozen or more—create “characters” who will travel about in this make-believe world, interact with its peoples, and seek the fabulous treasures of magic and precious items guarded by dragons, giants, werewolves, and hundreds of other fearsome things. The game organizer, the participant who creates the whole and moderates these adventures, is known as the Dungeon Master, or DM. The other players have personae—fighters, magic-users, thieves, clerics, elves, dwarves, or what have you—who are known as player characters. Player characters have known attributes which are initially determined by rolling the dice… These attributes help to define the role and limits of each character… There is neither an end to the game nor any winner. Each session of play is merely an episode in an ongoing “world.”3

This is what the cave sounds like when it speaks to outsiders: its diction is erudite and occasionally awkward (“treasures of magic”); it uses game terms as though their meaning will be obvious (what are attributes?); it raises as many questions as it answers. You who have never played could be forgiven for asking, what are the rules of D&D? If no one wins, how do you know if you’re playing well? Where’s the board? OK, listen up: there is no board. You play a character, as in theater, though you don’t usually act out your character’s words or deeds. Rather, you communicate about your character with other players and with the Dungeon Master, whose job is to speak for the world. You tell the Dungeon Master what you do; someone rolls some dice; the DM tells you what happens. Together you tell a story: a fantasy epic à la Tolkien or whomever you will; or rather, given that the game has no natural end, maybe we should call it a fantasy soap opera. Imagine for a moment that Adam and Brian are players, and Charlie is the DM. Their story might go like this:

CHARLIE: OK, you guys have just entered the mystical Caverns of Quasqueton. You’re in a 10-foot-wide corridor, which leads to a large wooden door.

ADAM: I’m going to open the door.

CHARLIE: Just like that?

ADAM: OK, maybe not. Brian, have your elf check the door.

BRIAN: Don’t tell my elf what to do. [Pause.] My elf checks the door.

CHARLIE: [Rolls dice.] It appears to be a normal door.

What may remain obscure, even now, is why people would choose to play D&D, all night, night after night, for years.4 Why intelligent human beings would find the actions of imaginary fighters, thieves, dwarves, elves, etc., as they move through a space that exists only notionally, and consists more often than not of dimly lit corridors, ruined halls, and big, damp caves, more compelling than books or movies or television, or sleep, or social acceptance, or sex. In short, what’s so great about Dungeons & Dragons?

Why intelligent human beings would find the actions of imaginary fighters, thieves, dwarves, elves, etc., as they move through a space that exists only notionally, and consists more often than not of dimly lit corridors, ruined halls, and big, damp caves, more compelling than books or movies or television, or sleep, or social acceptance, or sex. In short, what’s so great about Dungeons & Dragons?

2.0 THE HARLOT ENCOUNTER TABLE

The appeal of D&D is superficially not very different from the appeal of reading. You start outside something (Middle Earth; Dickens’s London; the fascinating world of mosses and lichens), and you go in, bit by bit. You forget where you are, what time it is, and what you were doing. Along the way, you may have occasion to think, to doubt, or even to learn. Then you come back; your work has piled up; it’s past your bedtime; people may wonder what you have been doing.

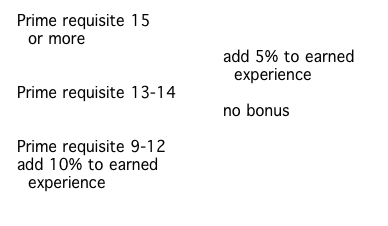

Once you set foot inside the cave, however, you see very quickly that D&D is quite different from a book, or movie, or soap opera. For one thing, there are a lot more rules. I remember opening the Basic D&D rulebook—I was eight years old—and coming to the “Table of Bonus and Penalties Due to Abilities,” which begins,

| Prime requisite 15 or more | add 10% to earned experience |

| Prime requisite 13-14 | add 5% to earned experience |

| Prime requisite 9-12 | no bonus |

By reading the accompanying text, I figured out that my character’s abilities—his strength, his intelligence, his wisdom or lack thereof, and so on—were each determined by rolling three six-sided dice, and that the “prime requisite” was the ability my character needed to do what he did (a fighter’s prime requisite is strength; a magic-user’s is intelligence, etc.). It would be several pages before I understood that “earned experience” referred to the experience points a character earns for killing monsters and amassing treasure, and which regulate his promotion to ever-greater levels of power and ability. And I remember how, as the meaning of these terms became clear, my bewilderment yielded to delight. The rules guaranteed the reality of the game-world (how could anything with so many rules not be real?), and, if they were hard to understand, at least they were written out, guessable and debatable, unlike the implicit, arbitrary, and often malign rules that people live by in the actual world.

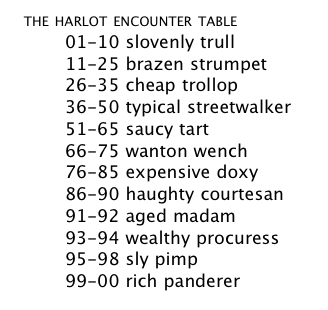

D&D is a game for people who like rules: in order to play even the basic game, you had to make sense of roughly twenty pages of instructions, which cover everything from “Adjusting Ability Scores” (“Magic-users and clerics can reduce their strength scores by 3 points and add 1 to their prime requisite”) to “Who Gets the First Blow?” (“The character with the highest dexterity strikes first”). In fact, as I wandered farther into the cave, and acquired the rulebooks for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, I found that there were rules for everything: what kind of monsters you could meet in fresh water, what kind you could meet in salt water, what wise men knew, what happened when you mixed two magic potions together. If you happened to meet a harlot in the game, you could roll two twenty-sided dice and consult a table which told you what kind of harlot it was.5 It would be a mistake to think of these rules as an impediment to enjoying the game. Rather, the rules are a necessary condition for enjoying the game, and this is true whether you play by them or not. The rules induct you into the world of D&D; they are the long, difficult scramble from the mouth of the cave to the first point where you can stand up and look around.6

2.1 THE INVENTION OF DUNGEONS & DRAGONS

D&D gets its appetite for rules from wargames, which have been around for thousands of years. The modern war game began in the late eighteenth century, when a certain Helwig, the Master of Pages to the German Duke of Brunswick, invented something called “War Chess”: instead of rooks and knights and pawns it featured cavalry, artillery and infantry; instead of castling it had rules for entrenchment and pontoons. The Prussians adapted Helwig’s game to train their officers; the French learned the value of wargames the hard way in 1870. In 1913, when the Prussians were again rattling their sabers, the British writer H. G. Wells came up with a game called Little Wars, which was played on a tabletop, with miniature lead or tin soldiers. Then, in 1958, a fellow named Charles Roberts founded the Avalon Hill game company, and published a board game based on the battle of Gettysburg. Gettysburg and its successors were wildly popular; all over America, college students and other maladjusted types began to recreate, in their dorms and basements and family rooms, the great battles of history.

One of these enthusiasts was a high-school dropout named Ernest Gary Gygax. In the late 1960s, Gygax was living in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, where he worked as an insurance underwriter. He was married to a Lake Geneva girl and had four children, but he remained an active gamer: together with a couple of friends, Gygax founded the grandly named International Federation of Wargaming, the Castles & Crusades Society, for medieval war gamers, and the Lake Geneva Tactical Studies Association, which met weekly in his basement. In the course of these meetings, he became friendly with a hobby-shop owner named Jeff Perren, and they co-authored a set of rules for medieval miniatures combat,7 called Chainmail, which was published in 1971.

Meanwhile, up in Minneapolis, a student named Dave Arneson was running Napoleonic miniatures games in his parents’ basement.8 Arneson got a copy of the Chainmail rules; only it turned out that medieval miniatures combat wasn’t very exciting,9 and Arneson and his fellow gamers looked for a way to spice it up. A fellow named Dave Wesley gave each player a personal goal: now the figurine on the table represented Sir So-and-So, and he had a rudimentary personality. This was the dawn of tabletop role-playing. Then Arneson issued a Star Trek phaser to a druid, much to the disgust of the other players: this was the dawn of tabletop fantasy role-playing, although no one seemed to realize it yet.10 The phaser wasn’t enough; Arneson spent a weekend eating popcorn and reading Conan novels, and at the end of it, he had an idea. The next time the Napoleonic miniatures people showed up in the Arnesons’ basement, they found a model of a castle on the sand table. They thought it was going to be some place in Poland, which they would storm or defend. Then Arneson told them that they were looking at the ruined castle of the Barony of Blackmoor, and that they were going to have to go into the dungeons and poke around. The Napoleonic miniatures people weren’t thrilled; they would have preferred to storm the castle. But they agreed to poke around. And around, and around.

In the fall of 1972, Arneson visited Lake Geneva and introduced Gygax to Blackmoor. Gygax liked the game, and he and Arneson worked together to develop a publishable version of the rules. The first edition of Dungeons & Dragons appeared in 1974. Gygax and his business partners, Don Kaye and Brian Blume, assembled the sets by hand in Gygax’s basement:11 they put stickers on the boxes, collated the rulebooks, folded the reference sheets. Even so, they didn’t know what they had on their hands. They called D&D “rules for fantastic medieval wargames,” and Gygax hoped to sell 50,000 copies, that being the approximate size of the wargaming market. At first, D&D seemed unlikely to meet even these modest expectations. It took eleven months for Tactical Studies Rules, which is what Gygax, Kaye and Blume called their partnership, to sell out the first thousand copies. But news of the game was traveling by word of mouth, from hobby shops to college dorms, from dorms to high schools. People called Gygax in the middle of the night to quiz him about the rules. The second thousand copies, also hand-assembled, sold in six months, and from then on sales increased exponentially. In 1975, Tactical Studies Rules incorporated and changed its name to TSR Hobbies; in 1979, the company sold 7,000 copies of the D&D Basic Set each month. Their gross income for 1980 was $4.2 million.

3.0 I’M A FIFTH-LEVEL DARK ELF WITH A +2 SWORD.12

What set D&D apart from its cousins, the war games, was, first of all, the thrill of “being” someone else. In 30 Years of Adventure: A Celebration of Dungeons & Dragons, a volume published in 2004 by Wizards of the Coast, celebrity gamer Vin Diesel remembers his twin brother selling him on D&D with the line that “[it’s] a game that allows you to be anyone you want to be….” Games designer Harold Johnson heard from a friend: “It’s a fantasy game. You get to play knights and wizards, clerics and thieves.” The appeal isn’t hard to understand, especially if “being” yourself isn’t all that much fun: if you are, say, a bookish adolescent male with few social skills and no magical powers to speak of.13 What’s more, D&D offers its players a moral clarity rarely found in the real world: your character has an alignment; he or she can be good or evil, lawful or chaotic. Most players choose good; the paladin, a virtuous knight with magical powers, is a perennial favorite, although the evil-leaning dark elf is also popular.

In practice, though, the transformation of player into character often turns out to be cosmetic: the fearless paladin and the sexy dark elf both sound and act a lot like a thirteen-year-old boy named Ted. And what Ted likes to do, mostly, is kill anything that crosses his path. It’s little wonder that Dungeons & Dragons was uncool in the 1970s and ’80s. Under the guise of role-playing, the game condoned behaviors that would get you ostracized (or worse) if you tried them in the real world. The dungeon adventures which were the game’s mainstay in the early ’70s had only two objectives: destroy all the monsters, and get all the treasure.14 Circa 1978, Gary Gygax wrote and published a series of adventures with a narrative arc: the characters begin by taking on a hill giant, and they are gradually drawn into the underground world of the Drow, or dark elves, one of Gygax’s best-loved creations. The story was compelling to the people who played the adventures, but this may have had less to do with its complexity than with the fact that there was a story at all. In any case, the ins and outs of Drow society only slightly mitigated the game’s bloody-mindedness; instead of destroying all monsters, the wise course now was to destroy some monsters.15

Women in the game—female players, female “non-player characters” who turned up in bars and dungeon cells—fared little better. Gary Alan Fine, a sociologist who published a book-length study of fantasy role-playing games in 1983, reported that “in theory, female characters can be as powerful as males; in practice, they are often treated as chattels.” Indeed, one of the players Fine observed16 reported that he didn’t like playing with women, because they inhibited his friends’ natural tendency to rape the (imaginary) women they met in-game:

Because a lot of people I know go in and pick up a woman and just walk off…. Some people get a little carried away and rape other people…. Well, I’ve seen a lot of players just calm down because of [females].17

You will not be surprised to learn that, in one 1978 survey of fantasy role-playing gamers, only 2.3 percent of respondents were female; in another, only 0.4 percent. Nor did TSR, in the early days, do much to remedy this situation (I recall a print ad for D&D, in which a tweenage girl is pictured playing with some boys, and enjoying herself: now that was a fantasy, I thought), perhaps because Gygax is a self-avowed biological determinist who believes that “women’s brains are wired differently… the reason they don’t play is that they’re not interested in playing.”

3.1 THIS IS B.A.D.D.

In 1979, an average of 6,839 young men were picking up Dungeons & Dragons each month: sooner or later there was bound to be trouble. And sure enough, that same year, a Michigan State student named James Dallas Egbert III disappeared after a game of D&D. The thing was, Egbert and his friends weren’t just rolling dice and moving lead miniatures around on a card table; they had been acting out their characters’ exploits in the university’s steam tunnels. It seemed possible that the game had gone too far, and that Egbert had been killed, or died by misadventure. A few weeks later, Egbert turned up in Morgan City, Louisiana, and revealed that D&D had nothing to do with his disappearance, but the case caused a sensation. The private investigator hired to find Egbert published a faintly lurid book called The Dungeon Master, which inspired a lurid novel called Mazes and Monsters, which inspired a made-for-TV movie of the same name, starring Tom Hanks. Meanwhile, in Washington state, a seventeen-year-old boy shot himself in the head. Witnesses said that he had been trying to summon “D&D demons” just minutes before his death. Was Dungeons & Dragons a blood sport? Was it a gateway to Satanism? A woman named Pat Pulling, whose son, a D&D player, had also committed suicide, started an organization called Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons, or, yes, B.A.D.D., and before long D&D had joined a pantheon of mostly cooler or at least more authentically dangerous phenomena which were said to be corrupting America’s youth: marijuana, rock and roll, free love, LSD, heavy metal.

Even from the point of view of a teenage boy who would have liked nothing better than to be corrupted by any of the phenomena listed above, if corrupted meant meeting girls or even just getting out of the house, the furore over D&D was hard to understand. Didn’t the grown-ups understand what losers we were? That all we did was roll dice and shout and stuff our faces with snacks? Evidently not: in 1989, Bill Schnoebelen, a reformed Milwaukee Satanist, wrote an article called “Straight Talk on Dungeons and Dragons,” which can still be found on Chick Ministries’ website.18 He listed the “brainwashing techniques” which D&D uses to lure its players into the devil’s world, among which are:

- Fear generation—via spells and mental imaging about fear-filled, emotional scenes, and threats to survival of FRP [fantasy role-playing] characters.

- Isolation—psychological removal from traditional support structures (family, church, etc.) into an imaginary world. Physical isolation due to extremely time-consuming play activities outside the family atmosphere.

- Physical torture and killings—images in the mind can be almost as real as the actual experiences. Focus of the games is upon killings and torture for power, acquisition of wealth, and survival of characters.

- Erosion of family values—the Dungeon Master (DM) demands an all-encompassing and total loyalty, control and allegiance.

Most of which is, of course, true, though I’d quibble at Schnoebelen’s emphasis on torture—usually it was enough for us to kill the monsters without torturing them first—and at the logic of No. 4: the DM could demand total loyalty as much as he wanted, but he was unlikely to get it from us; we were too busy finding ways to reduce his creation to rubble, or eating ice cream. But the mention of “spells” in No. 1 is bizarre. Did Schnoebelen think that the players were actually capable of working magic? Further study of his article suggests that he did. “Just because the people playing D&D think they are playing a game doesn’t mean that the evil spirits (who ARE very real) will regard it as a game. If you are doing rituals or saying spells that invite them into your life, then they will come—believe me!”19 This was every player’s fantasy: that the magic in the game would work, that we would become our characters, for real, and be rid once and for all of our lowball ability scores, our pathetic skills, our humdrum real-life equipment. If wishing, or talking, or even praying could have made it so, then there would have been a lot of dark elves out there, brandishing their +2 swords, and—perhaps the people at Chick Ministries will find this reassuring—a lot of paladins, too, curing us of our diseases, protecting us from evil within a ten-foot radius.

Despite a near-total absence of evidence linking D&D to Satanism, or magic, or anything, really, except obesity and lower-back pain, Pat Pulling and Gary Gygax appeared on a special investigative episode of 60 Minutes, which left viewers with the impression that there was “strong evidence” that Dungeons & Dragons could inspire teenagers to kill themselves, or each other. Gygax started getting death threats in the mail, and he hired a bodyguard. Yet notoriety had its advantages: in 1981, with the Egbert case still fresh in the public’s mind, TSR’s revenues quadrupled, to $16.5 million.

3.1.1 A FURTHER NOTE ON RITUAL

As silly as Schnoebelen’s fears may sound to us now, he did get one thing right: Dungeons & Dragons is not a game. The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss notes that “Games… appear to have a disjunctive effect: they end in the establishment of a difference between individual players or teams where originally there was no indication of inequality. And at the end of the game they are distinguished into winners and losers.” Which is, as noted above, not true of D&D: “there is neither an end to the game nor any winner.” But if D&D isn’t a game, then what is it, exactly? One theorist of fantasy role-playing games proposes, following Lévi-Strauss, that D&D is, in the strict sense of the term, a ritual. “Ritual, on the other hand,” this is Lévi-Strauss again, “is the exact inverse: it conjoins, for it brings about a union… or in any case an organic relation between two initially separate groups….”20 D&D conjoins: this is not the first thing you notice when you enter the cave; nor is it mentioned very often by the game’s recruiters (or by its detractors), who prefer to talk about killing and money and other things the uninitiated can understand. And yet it is an essential feature of the game—ritual—whatever you want to call it. Adam’s fighter may be more powerful than Brian’s elf, but if the fighter kills the elf, or even pisses him off seriously, who will find the secret door? In order to get very far in the cave, the players need to work together.21 Which would make D&D not very different from any other team sport, if there were another team; but there isn’t. The remarkable thing about D&D is that everyone has to play together. Even the DM, who plays all the monsters and villains, has to cooperate; if he doesn’t—if he kills the entire party of adventurers, or requires players not to cheat on life-or-death dice rolls—the chances that he will be invited to run another session are small.

Here I am tempted to advance a wild argument. It goes like this: in a society that conditions people to compete, and rewards those who compete successfully, Dungeons & Dragons is countercultural; its project, when you think about it in these terms, is almost utopian.22 Show people how to have a good time, a mind-blowing, life-changing, all-night-long good time,23 by cooperating with each other! And perhaps D&D is socially unacceptable because it encourages its players to drop out of the world of competition, in which the popular people win, and to tune in to another world, where things work differently, and everyone wins (or dies) together. You will object that a group of teenage boys slaughtering orcs and raping women doesn’t sound like utopia. Granted. But among teenage boys whose opportunities for social interaction were otherwise not great, D&D was like a door opening. Forget for a moment that behind the door there were mostly monsters and darkness. For us, for the people who played, what waited behind that door was a world, and the world belonged to us. We could live in it as we really were; we could argue about its rules; we could learn how, by working together, to get the better of it. For some of us it was a lesson: the real world could, on occasion, and by similar means, be bested. For others of us, who never really left the game: at least we had a world.

In fact, the ability to function in another world may be the game’s most important legacy. D&D provided a conceptual framework for some of the most popular computer games of the 1980s: Wizardry, Ultima, and Zork all involve poking around in dungeons and slaying monsters. Wizardry begat Wolfenstein 3D, Wolfenstein begat Doom, Doom begat Quake, and Quake begat Halo: it may be an exaggeration to say that these games could never have existed without Dungeons & Dragons, but D&D certainly showed a lot of people what kind of fun they could have by participating in a virtual reality. The game’s influence is even clearer on the massively multiplayer online role-playing games: Everquest, Ultima Online, World of Warcraft, and D&D Online, which made its début early this year. Almost every aspect of the old tabletop game has been recreated in these pretty, expensive beasts, except the pleasure of being in the same room with other human beings. Perhaps the people who spend thirty hours a week playing World of Warcraft, the people who used to buy and sell Everquest magic items for real dollars on eBay, and the people who buy online characters that have been “leveled up” by workers in the Third World, don’t miss the companionship. D&D taught us to live in an imaginary place—a literal utopia—and if that place is engrossing enough, what does it matter if there are other people in your living room or not? And yet it sounds lonely to me. The great thing about old-fashioned, paper-and-pencil D&D was that it straddled the virtual world and the real one: when the game was over, the dungeons and dragons went back to their notebooks, but you got to keep your friends.

4.0 DADDY NEEDS A NEW SWORD OF WOUNDING

Even now, more than thirty years after its invention, people are still playing Dungeons & Dragons. Not quite the game I played as a child: a Second Edition appeared in 1989; it tidied up the hodgepodge of rules which Advanced D&D had become, stripped the paladin of many of his powers, and was duly reviled by most old-school players. By then, Gygax had lost control of TSR; he was replaced by Lorraine Dille Williams, the heiress to the Buck Rogers fortune.24 Williams was not generally beloved by those who worked under her; nonetheless, the company managed to publish some good material: the Goth-y Ravenloft campaign setting, the killer Return to the Tomb of Horrors, and a number of successful fantasy novels. But the market for the game had stopped growing. Everyone who was going to buy the rulebooks had already done so; in order to keep selling its products to gamers, TSR had to come up with new rulebooks. Thus we got, among other things, The Complete Book of Gnomes & Halflings, 127 pages on “The Myths of the Halflings,” “A Typical Gnomish Village,” etc.

Meanwhile, TSR spent a lot of money pursuing licensing deals and starting lawsuits, several of them against Gygax, to protect its copyrights. Changes in the bookselling industry further eroded the company’s revenues; TSR went deeply into debt, and in 1997 Williams sold the company to Wizards of the Coast, which was best known for a collectible card game called Magic: The Gathering. In 2000, Wizards published a third edition of Dungeons & Dragons, which systematized what had been erratic or arbitrary in the first two editions. Reactions to the Third Edition have generally been positive, although some players grumble that the rules are now too consistent. William Connors, a designer for TSR and, briefly, for Wizards, says that with the Third Edition, “the heart and soul of the game was gone. To me, it wasn’t all that much more exciting than playing with an Excel spreadsheet.”25 A gamer I talked to in a Manhattan hobby shop says that he’s afraid the Third Edition is for “power campaigners”: people who exploit the rules to make their characters as powerful as possible, at the expense of role-playing plausibility or narrative interest. Nor has the proliferation of rulebooks been checked. Wizards of the Coast publishes about two dozen official rulebooks for D&D, not counting dozens of supplementary books by other publishers; and the Third Edition rulebooks have already been superceded by Edition 3.5.

Meanwhile, a stranger transformation has taken place: D&D is no longer uncool. In part, this is because the game has become more sophisticated, more narrative-based, less single-mindedly devoted to the destruction of monsters. A live-action role-playing game26 called Vampire: The Masquerade introduced members of the Goth subculture to gaming; some of them switched over to D&D, with the result that there are more women gamers now, and they are in a position to make their own version of the game.27 Also, some of the people who create mass culture now were once themselves gamers. There are graphic depictions of D&D in The X-Files and Freaks & Geeks and Buffy the Vampire Slayer; Gary Gygax has even made a cameo appearance on Futurama. Vin Diesel admits happily to being a gamer; Steven Colbert admits to having been one. Mostly, though, D&D has become acceptable because people get used to things. As John Rateliff, who has worked on the game since the early ’90s, puts it, “It’s kind of like rock music. All it takes is time for people to get over their fear of the new and find out whether it’s something they might actually enjoy trying themselves.”

The question is, are new people joining the game? According to a recent survey, there are four million D&D players in the United States, and that number hasn’t changed much in the last few years. The majority of the players are between eighteen and twenty-four years old, then you have the twelve- to seventeen-year-olds and the twenty-five- to thirty-four-year-olds, who play in roughly equal numbers; then the thirty-five to forty-five-year-olds, and finally the eight- to eleven-year-olds, very few of whom play D&D, or have even heard of the game. The survey notes cheerily that a third of these tweenagers expressed interest in learning about D&D, but whether Wizards of the Coast can translate this interest into sales—and players—remains to be seen. Last summer I visited Gen Con, a gaming convention that has been held annually since 1968 when Gary Gygax and his friends rented out the Lake Geneva Horticultural Hall.28 The convention has grown to about 26,000 attendees annually, and it has moved, from Lake Geneva to Milwaukee and now to Indianapolis, where it occupies the convention center downtown, between the state house and the football stadium. I didn’t see many twelve- to seventeen-year-olds, and the ones I did see were gathered in the Xbox area, blowing each other away in Halo 2. The people who filled the gaming rooms and prowled the Exhibit Hall were men and women in their twenties and thirties, some of them in doublets and hose, some in Goth regalia, most in shorts and T-shirts and jeans and sneakers and sandals. If they had dispersed into the streets of Indianapolis no one would have known them for anything but citizens, if it weren’t for their convention badges and the fervent light in their eyes. Of course, these were the people who loved gaming enough to travel to central Indiana and spend several hundred dollars on entrance fees, game tickets, hotels and restaurants, which, incidentally, were serving special game-themed meals: whatever else gamers may be, they are apparently willing to spend money on almost anything game-related.29 You wouldn’t expect a fifteen-year-old to turn up here on his own—except that in the early days of Gen Con, you heard stories about kids who did just that. They came by bus and hitchhiked to the convention center; they gamed all day and slept in the hallways at night because they couldn’t afford hotel rooms.

I didn’t play much D&D while I was at Gen Con, in part because the Third Edition rules are too different from the rules I grew up with, and in part because tournament play isn’t my cup of tea: it’s goal-directed, without much emphasis on role-playing.30 However, according to the same survey, the largest group of D&D players are just my age: thirty-five-year-old men make up almost 10 percent of the D&D-playing population (twenty-two-year-olds are next, at 7 percent, then thirty-two-year-olds, at 5.5 percent). These are the people whose adolescence corresponds to the peak of D&D’s popularity, the ones who were in college when Second Edition came out and the game’s popularity surged again. At the risk of drawing false conclusions, I will venture to speak for my demographic: we were hooked early, and the hooks went deep into us. Few of the people I talked to or read about, who have been involved with gaming since the early ’90s or longer, show any sign of wanting to quit. John Rateliff says, “If I’m still alive [at seventy-five], I’ll still be playing. Why not? I intend to still be listening to the music I like and reading the books I like at [that age], if I’m still able. Why shouldn’t I still be enjoying my favorite hobby?” Skip Williams, who has been working on D&D since First Edition days, has left Wizards of the Coast, but he can’t seem to leave gaming; right now he’s sprucing up a bunch of “classic monsters” for a new monster book. Even Brian Blume, who left TSR after a bitter struggle with Gary Gygax, and seems unlikely to have fond memories of those days, was recently roped into a game of Boot Hill, the Wild-West-era role-playing game he co-wrote in 1975. “I was at a games convention in Des Moines, and a fellow was running a big barroom shootout, and I got involved. It was a big nostalgic moment.” Apparently the referee begged Blume to play the sheriff, the toughest role, because usually in those situations the sheriff is the first one to be shot. “Were you shot?” I asked. “I role-played it a little,” Blume said, and chuckled. “I got about halfway through, and I’m happy with that.”

If Wizards of the Coast can’t find a way to make Dungeons & Dragons compelling to children, then the day will come when D&D is the equivalent of bingo or shuffleboard, played by forgetful old men in retirement homes, community centers, and, yes, church basements. “I’m an elf of some sort,” one of the players will say. “Where did I put that character sheet?” But the best hope for D&D’s future currency may be that we thirty-five-year-olds will overcome our geekdom for at least long enough to start families. “My kids are coming tomorrow,” said one Gen Con visitor, a thirty-six-year-old man who had been playing D&D for twenty-four years. “They’ve never played before, but I thought I’d give them the chance to try it out.” There’s no reason to think that children have lost the desire to become elves, warriors, wizards, and thieves. If we’re lucky, they’ll be willing to play with their parents.

THE SCENARIO, OR,

WAYNE AND I MEET

THE WIZARD

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

We are far enough into the cave now that I can tell you that I have mixed feelings about Dungeons & Dragons. I played fantasy role-playing games more or less incessantly from 1978, when my father brought home the D&D Basic Set, until 1985, when I changed high schools and fell out of constant contact with my gamer friends. I played so much that it’s hard for me to understand in retrospect how I managed to do anything else, and the truth is that I didn’t do anything else. I was a mediocre student; I didn’t see hardly any of New York City, where I lived; I knew less about girls than I did about the Gelatinous Cube (immune to cold and sleep; takes normal damage from fire). I played at friends’ houses; I played in the school cafeteria; I played in the hallway between classes; I cut class to play in whispers in the library. I hesitate to say that I was addicted to role-playing games only because I never knew what it was like to go without them; in D&D I had found something I loved more than life itself. Then a number of things happened, and for fifteen years I didn’t think about D&D at all. I was living in San Francisco, where dungeon referred to something entirely different, and life seemed mutable and good, like a game. In December 2001, I moved back to New York, and soon afterward I began to think about D&D again. It turned out that my agent’s office was a block from the Compleat Strategist, the hobby shop where I used to buy my role-playing games. I wasn’t eager to revisit that part of my life, which I thought of as a dangerous mire from which I had miraculously escaped, but I slunk into the store. Nothing had changed: nothing. The same pads of hex paper31 stood in the same racks by the door, their covers bleached by twenty years of sunlight. It was as if the place had been preserved as a museum to the heyday of tabletop role-playing games; it was as if someone had set out to demonstrate that you could go home again. Maybe I wanted to come home; maybe I had never really left that mire; maybe I needed to own up to an old love—an old habit—in order to make my life whole. This thing of dorkness I acknowledge mine. All I knew was that I had to do something about Dungeons & Dragons: put it behind me once and for all, or return to its warm, embarrassing embrace. For a long time I did neither. Then one day, when my friend Wayne and I were talking about our gaming days, he said, why don’t you interview E. Gary Gygax? It made sense. Gygax was the source of Dungeons & Dragons, the wizard who cast the original spell.32 Perhaps by going to see him I could get the spell lifted at last. And besides, as Wayne was quick to point out, how cool would it be to meet Gary Gygax? Not to mention, he said, the possibility that we could convince him somehow to play D&D with us. We, he said, because of course it had to be both of us. You need three people to play D&D; besides, Wayne was under the spell, too.

LAKE GENEVA

Gary Gygax still lives in Lake Geneva, a resort town about two hours northeast of Chicago. Incorporated in 1844, it has a cutesified little downtown and a historical museum in which a street from Old Lake Geneva is haphazardly recreated, down to the Indian arrowheads, barber poles, and photographs of former firemen. There’s an excellent video arcade, with a vintage Robotron console still in good working order. There’s a place that sells Frozen Custard Butterburgers, two distinct Midwestern delicacies, I hope. There’s a big lake, which freezes in winter; people build a shantytown on the ice and go fishing for bass and cisco. Gygax was born in Chicago, but he grew up here, and he returned to Lake Geneva in his mid-twenties to raise his family. It’s not hard to see how Dungeons & Dragons would come out of a place like this, a place where, on a fine spring night, you can find the town’s youthful population walking up and down Main Street, from the ice cream parlor to the arcade, from the arcade to the lake. If you grew up here, you would need to dream of something.

Gygax and I agreed to meet on a Saturday in May. I said I’d come at eleven; he said, come at nine, I’ll make you breakfast. So Wayne and I found ourselves outside his big yellow house one gray morning, wondering if we were worthy to meet the Wizard. Then he let us in. Gygax does not look un-wizardly: he has a long white ponytail, a white beard and fierce black eyebrows, like Gandalf. He is shorter than Gandalf, however, and stouter, and more cheerful: picture him as a cross between Gandalf and Bilbo Baggins.33 A lifelong smoker, Gygax sounds a bit like Tom Waits, especially when he laughs, and he laughs often. He had a mild stroke in 2004, and his doctor ordered him to quit cigarettes; now he smokes Monterrey Black and Mild cigarillos, one after the other. He led us to a table at the corner of the screened porch, which was cluttered with a long life’s worth of wicker furniture and floor lamps. In the center of the table lay a big pleather-bound copy of the Holy Scriptures: maybe it was there by accident, or maybe Gygax wanted to reassure us that he wasn’t a Satanist. I had told him that I was writing for a magazine called the Believer, after all. As we sat down, his wife appeared from within the house, saw us, and cried, “They’re two hours early!” Gygax excused himself and conferred within. Then he came out as if nothing had happened; he lit a cigarillo and began to speak.

E. Gary Gygax was born in 1938. His father, Ernst Gygax, came to America from Switzerland; he settled in Chicago, and one summer he went to a dance in Lake Geneva. There he met Almina Emilie Burdick, the daughter of an old Lake Geneva family, married her, and returned to Chicago, not necessarily in that order. Ernst wanted to play the violin, he put himself through music school and for a time he played with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, but when he saw that he would never make first chair he gave it up and sold clothes instead. He was, Gygax says, an attentive father, and he must have been a permissive father also, because Gygax’s childhood was marked by a disregard for rules and obligations. He went to school half a block from his childhood house in Lake Geneva, but he was rarely to be found there. “It was just dull and stupid,” he says, “and you know, I had so many other things I wanted to do. I had a day full of active going out with my friends, playing chess, hanging around, trying to pick up girls, usually without any success whatsoever. What? Sit home? Do school work? Unthinkable.” Instead he threw firecrackers at the chief of the waterworks, shot .22s down empty streets, and haunted the abandoned Oak Hill Sanatorium, a five-story brick building that overlooked Lake Geneva. He played make-believe with the kids next door: he was a cowboy named Jim Slade, and he got the drop on his friends so often that they quit in disgust.

Easygoing as he sounds, Gygax likes to win; there is in him more than a little of the Ernst who would be first violin or nothing. You can hear it in the way that he talks about the invention of Dungeons & Dragons. Gygax and Dave Arneson are credited equally as authors of the original game, but as Gygax tells it, Arneson had at most a minor role in the process. When I asked him whether Arneson ran his Blackmoor campaign before the D&D rules were written—a fact which seems beyond doubt, and which establishes Arneson’s involvement in the creation of the game—Gygax answered evasively, “Um, he was up in Minneapolis, and he ran a lot of game campaigns. He was using my Chainmail rules for a campaign and I think that was called Blackmoor.” Arneson, for his part, claims that he scrapped the Chainmail rules early on, in favor of a more complex system derived from Civil War–era naval simulations.34 And the gloom thickens: Arneson sued TSR more than once for royalties and a co-authorship credit on the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rulebooks; the court decided in his favor, but as far as I know he never got the credit.35 Arneson is legally enjoined from discussing the matter, and Gygax doesn’t like to talk about it either, perhaps because it reflects badly on him, or perhaps because he is at heart a Midwesterner, and so not disposed to speak ill of his fellow man. As we talked, though, it became clear that Gygax thinks strategically about more or less everything. He mentioned that his son Luke had served in the first Gulf War: “I told him when he was over there for Desert Shield, I said, ‘Well, here’s what’s going to happen. The [Coalition’s] left flank is gonna come around and pocket all those dummies!’ And that’s exactly what they did. I couldn’t believe it, you know? Boy, Saddam Hussein’s not a general.” Wayne asked Gygax what he would have done in Saddam’s place. Gygax thought about it, then answered, “I would have gotten right out of Kuwait…. You’d have to slow ’em up and you’d try to fight a guerilla war.” He conceded that against Allied airpower, the Iraqis would have lost anyhow. But it didn’t stop him from figuring out how to make the best of a weak position.

Gygax’s own position at TSR had become weak by 1982. In order to finance the publication of D&D in 1974, he and his partner Don Kaye had brought in a friend named Brian Blume, whose father, Melvin, was willing to invest money in the company. Kaye died in 1976, and Brian got his brother Kevin named to TSR’s board. Gygax was the president of TSR, but the Blumes effectively controlled the company; to keep Gygax further in check they brought in three outside directors, a lawyer and two businessmen who knew nothing about gaming but always voted with the Blumes. So Gygax moved to Los Angeles, and became president of Dungeons & Dragons Entertainment, which produced a successful D&D cartoon, and set out to produce a D&D movie. This was, to put it mildly, a strategic retreat. Gygax rented King Vidor’s mansion, high up in Beverly Hills, with a bar, a pool table, and a hot tub with a view of everything from Hollywood to Catalina. He had a Cadillac and a driver; he had lunch with Orson Welles, though he mentions with Gygaxian modesty that “I find no greatness through association.”36 Here a whiff of scandal enters the story. Gygax had separated from his first wife, the mother of five of his six children; he had not yet married his second wife, Gail.37 In the interim, well, it was Hollywood, and Gygax was in possession of a desirable hot tub. Gygax refers to the girlfriends who used to drive him around—he doesn’t drive; never has—and to a certain party attended by the contestants of the Miss Beverly Hills International Beauty Pageant. But he also mentions that he had a sand table set up in the barn, where he and the screenwriters for the D&D cartoon used to play Chainmail miniatures. This is perhaps why Gygax, unlike other men who leave their wives and run off to L.A., is not odious: his love of winning is tempered by an even greater love of playing, and of getting others to play along. He ends the story about the beauty pageant girls with the observation that Luke, who was living with him at the time, was in heaven, seated between Miss Germany and Miss Finland.

Gygax spent a lot of money in Hollywood. According to Brian Blume, he paid the screenwriter James Goldman, best known for A Lion in Winter, $500,000 for the script of the would-be D&D movie, but a movie deal remained elusive. Meanwhile, TSR had other problems: believing that it would continue to grow indefinitely, the Blumes had overstaffed the company; they invested in expensive computer equipment, office furniture, a fleet of company cars. But TSR’s growth spurt was over. By 1984, the company was $1.5 million in debt, and the bank was ready to perfect its liens on TSR’s trademarks: in effect, to repossess Dungeons & Dragons. Gygax got word that the Blumes were trying to sell TSR, and he returned to Lake Geneva, where he persuaded the board of directors to fire Kevin Blume and published a new D&D rulebook to raise cash.38 At the same time, Gygax looked for people to invest in the company. While he was living in Los Angeles, he’d become friends with a writer named Flint Dille, with whom he collaborated on a series of choose-your-own-adventure-type novels. Flint arranged for Gygax to meet his sister, Lorraine Dille Williams, who, in addition to the Buck Rogers fortune, had experience in hospital and not-for-profit administration. Gygax asked Williams to invest in TSR; Williams demurred, but agreed to advise Gygax on how to get the company back on its feet.

In May, 1985, Gygax exercised a stock option which gave him a controlling interest in TSR; he named himself CEO, and hired Williams as a general manager. And here the darkness of the cave becomes so great that almost nothing can be seen. Some time in the summer of 1985, Williams, impressed by the potential value of TSR’s intellectual property, decided to take control of the company. She bought out the Blume brothers, who wanted to quit anyway; but first she got Brian Blume to exercise his stock option, which meant that Williams ended up with a majority of the shares of TSR. At this point, Brian Blume says, “ugly things happened.” Blume says that Gygax tried to fire Williams and hire Gail Carpenter (the future Mrs. E. Gary Gygax) in her place. Gygax says that he wanted to fire Williams when she was still only a manager, but was advised not to, and didn’t, until it was too late. Flint Dille speculates that Gygax wanted the company for himself. “Gary was interested in running TSR again. He was going to replace the board with his then-girlfriend, family members, and pets. And Lorraine said, you can’t do that. We don’t want to replace one tyranny with another.”

For nearly a year after we met Gygax, Wayne and I entertained various wild theories about what had really happened, and why. Then I found Lorraine Williams. She has kept silent about TSR since she left the company, in 1997, but she agreed to talk with me for some reason, perhaps because I didn’t sound like a hard-core gamer, or because even keeping silent no longer seems important to her after all these years. I hoped for something extraordinary from our conversation: a revelation, a glimmer of light in the dark heart of the cave. I was disappointed. “There’s no great, hidden story,” Williams told me, “as much as people would like there to be one.” She saw the potential for TSR to move beyond the sluggish market for role-playing games: “If you look at the track record of what has been published by TSR, and how many people in the fantasy and science fiction area got their start publishing with TSR, it’s impressive. And I found that exciting. I also saw an opportunity that we were never really able to capitalize on, and that was the ability to go in and develop intellectual property.” She moved in. “And it was my intention at that time,” she said, “and I really thought that Gary and I had actually worked out the deal, that he would continue to have a very strong role, a leading role in the creative process, and I would take over the management. But that didn’t work for a bunch of really extraneous reasons.” Williams declined to say what those reasons were, but her brother speculates, plausibly, that they had to do with the Los Angeles operation: basically, Gygax didn’t want to give up King Vidor’s mansion, not when a movie deal could come through any day, not when he was having so much fun.39 Gloom, gloom.

When Gygax learned that Williams had bought the Blumes’ shares, he tried to block the sale in court. He lost. Lorraine Williams had outmaneuvered him, and she would continue to do so through the 1980s and ’90s, thwarting his attempts to create games which were, in her eyes, infringements on TSR’s intellectual property.40 Gygax succumbed to the business equivalent of air superiority. In 1986, he became the chairman of the board of directors of a company called New Infinities Productions, which published the Cyborg Commando role-playing game, which has been utterly lost, like most of the role-playing games published in the 1980s. Not even the Compleat Strategist stocks it anymore.

King Vidor’s mansion has been torn down; Gary Gygax is back in an old, cluttered house a few blocks from where he grew up. He has sold or renounced his rights to Dungeons & Dragons, and the money he made in TSR’s fat years seems mostly to be gone, too. He continues to write D&D supplements with names like Gary Gygax’s Fantasy Fortifications, but the market for such work is small: a third-party D&D title is doing well if it sells 5,000 copies. Gygax is still designing his own games, too. He worked for a while on a fantasy role-playing game called Dangerous Journeys, and now he’s working on one called Lejendary Adventures, a rules-lite alternative to the behemoth that Dungeons & Dragons has become. I haven’t played Lejendary Adventures, but to judge from the rulebook the game seems to be haunted by the specter of copyright infringement: characters are called avatars; classes are called orders; experience points are called merits; the elf has been renamed the Ilf. This despite the fact that elf is uncopyrightable: it’s as if Gygax were still dodging Lorraine Williams after all these years. And yet he doesn’t seem to feel much rancor, or much regret. Perhaps that’s because, win or lose, Gygax has made a whole life of playing games; and he is still playing. He has a weekly game of Metamorphosis Alpha, a science-fiction RPG, with Jim Ward, the game’s author. He plays old-fashioned D&D regularly with his son, Alex, and Ward, and sometimes with fans who make pilgrimages to Lake Geneva. And no one ever comes to ask why he isn’t in school! No wonder he laughs so often.

THE TEETH OF BARKASH-NOUR

Wayne and I took Gygax to lunch at an Italian restaurant on the outskirts of Lake Geneva: an expensive place, Gygax warned us. Our sandwiches cost six or seven dollars each. After lunch, we returned to his house to play some Dungeons & Dragons. Wayne and I felt curiously listless; it had already been a long day of talking; Wayne wasn’t sure he remembered how to play; I would have been happy to go back to our motel room and sleep. This happens to me often: I decide that I want something; I work and work at it; and just as the object of my quest comes into view, it suddenly comes to seem less valuable, not valuable at all. I can find no compelling reason to seize it and often I don’t. (This has never been the case, curiously, in role-playing games, where my excitement increases in a normal way as the end of the adventure approaches. Which is probably another reason why I like the games more than the life that goes on around them, and between them.) I wonder if we would have turned back, if Gygax hadn’t already gone into the house and come back with his purple velvet dice bag and a black binder, a module he wrote for a tournament in 1975. This was before the Tolkien estate threatened to sue TSR, and halflings were still called hobbits. So I got to play a hobbit thief and a magic-user and Wayne played a cleric and a fighter, and for four and a half hours we struggled through a wilderness adventure in a looking-glass world of carnivorous plants, invisible terrain, breathable water, and so on. All of which Gygax presented with a minimum of fuss. The author of Dungeons & Dragons doesn’t much care for role-playing: “If I want to do that,” he said, “I’ll join an amateur theater group.” In fact, D&D, as DM’ed by E. Gary Gygax, is not unlike a miniatures combat game. We spent a lot of time just moving around, looking for the fabled Teeth of Barkash-Nour, which were supposed to lie in a direction indicated by the “tail of the Great Bear’s pointing.” Our confusion at first was pitiable, almost Beckettian.

GYGAX: You run down northeast along the ridge, and you can see the river to your north and to your northeast. So which way do you want to go?

PAUL: The river is flowing south.

WAYNE: Which is the direction we ultimately want to go, right?

PAUL: We have to wend in the direction of the tail of the…

PAUL, WAYNE: “Great Bear’s pointing.”

PAUL: But we have no idea which way that is.

WAYNE: Tail of the Great Bear’s pointing. Maybe we should go north.

The sky clouds over; raindrops fall; the clouds part and the light turns rich yellow. The screen porch smells of cigar smoke. I want to go outside, to walk by Lake Geneva in early May, to follow the beautiful woman Wayne and I saw walking by the shore, to meet a stranger, to live. But I can’t get up. I roll the dice. I’m not tired anymore; I’m not worried about making a fool of myself in front of Gygax, who obviously couldn’t care less. And something strange is happening: Wayne and I are starting to play well. We climb a cliff by means of a magic carpet; we bargain with invisible creatures in an invisible lake. We steal eggs from a hippogriff’s nest; we chase away giant crabs by threatening them with the illusion of a giant, angry lobster.41 The scenario was designed for a group of six or eight characters, but by dint of cooperation and sound tactics (basically, we avoid fighting any monster that isn’t directly in our path) we make it through, from one page of Gygax’s black binder to the next. So we come to the final foe, the Slimy Horror, which turns our two spellcasters into vegetables; my hobbit thief and Wayne’s fighter don’t stand a chance against it. “That was pretty good,” Gygax says. He lets us read through the scenario, noting all the monsters we didn’t kill, all the treasure that was never ours. The Teeth of Barkash-Nour are very powerful: one of them increases your character’s strength permanently; another transports you to a different plane of existence. We were so close! So close, Wayne and I tell each other. We did better than we ever expected to; in fact, we almost won.

POSTSCRIPT

I would like to tell you that playing D&D with Gary Gygax lifted whatever spell I was under, and that when we left Lake Geneva, I embarked on a new life, unhaunted by the past. But here, outside the cave, things are rarely so simple. I still eye my weatherbeaten copy of the Players Handbook, with Gygax’s face all over the cover, and think about how much fun it would be to go in one more time. Wayne has moved to another city, but he and I are talking about meeting up at Gen Con this summer. In the meantime, we both have work to do. Maybe that’s all the peace you can make with the past: you agree that it can come back, but you make it meet you for just a weekend, at a convention center in a city far from your home. Or maybe that’s just my way of making peace.

I talked to Gary Gygax again in March of this year, to ask, among other things, if there was any truth to the rumor that he was diagnosed with stomach cancer in the early 1980s, and that he moved to L.A. because he didn’t want to spend the last six months of his life fighting with the Blume brothers in Lake Geneva. “No,” he said. “I have an abdominal aortic aneurysm, though.” He told me that he’d found out about it in January; the doctors tell him it’s inoperable. One day it will rupture and that will be the end. “I’m in no hurry,” he said. And indeed, here he was, telling me about Elastolin plastic miniatures, and a hobby-shop owner named Harry Bodenstadt, who used to run a game called the Siege of Bodenburg, in order to sell miniature castles to war gamers in Wisconsin in the 1960s. From which you could conclude, I guess, that games are everything for Gygax, or that everything is a game; but I don’t think that would be quite right. I think that he has found a way to live.

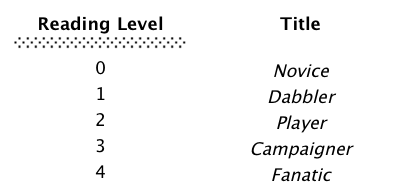

1 How many of these entrances do you recognize? The fourth is from Module S3: Expedition to the Barrier Peaks; the third is from Module D1: Descent into the Depths of the Earth; the second is from Module S2: White Plume Mountain, and the first is from Module B1: In Search of the Unknown. In the spirit of the game, you might want to use your score on this quiz to assign yourself a Reading Level, from 0 to 4, which will correspond, roughly, to your familiarity with old-school D&D. If you like, you can even give yourself a title: I’ll key further remarks in the notes to these reading levels. Which means, you novices and dabblers, that you will be drawn into the cave, willy-nilly.

1 How many of these entrances do you recognize? The fourth is from Module S3: Expedition to the Barrier Peaks; the third is from Module D1: Descent into the Depths of the Earth; the second is from Module S2: White Plume Mountain, and the first is from Module B1: In Search of the Unknown. In the spirit of the game, you might want to use your score on this quiz to assign yourself a Reading Level, from 0 to 4, which will correspond, roughly, to your familiarity with old-school D&D. If you like, you can even give yourself a title: I’ll key further remarks in the notes to these reading levels. Which means, you novices and dabblers, that you will be drawn into the cave, willy-nilly.

2 Note for Level 0-1 Readers: D&D is now published by Wizards of the Coast, a division of the toy manufacturer Hasbro.

3 TSR Hobbies, Understanding Dungeons & Dragons, 1979. Quoted in Gary Alan Fine, Shared Fantasy: Role-Playing Games as Social Worlds (Chicago: U Chicago Press, 1983), about which more later.

4 Note for Level 0 Readers, to which Level 2-4 Readers will probably object: Especially given that the actions described by the players (and taken by the characters) tend to be repetitive: walking down corridors, opening doors, fighting monsters, looting corpses, etc. A very great variety of actions are possible in the game: your character could gather wildflowers on the mountainside, or go back to town and start a dry-goods business. In practice, however, the players and the DM usually agree to keep their play within the bounds of the scenario the DM has prepared: an underground dungeon, a nasty spot of wilderness, etc., where there are monsters to be fought and treasure to be found. Although see note 27, below.

5. I reproduce it here in full as it appeared in the Dungeon Master’s Guide:

What, you may ask, is the difference between a “brazen strumpet” and a “wanton wench”? I don’t know, and it doesn’t matter; this is a rule which exists purely for its own sake. Here you have one reason why D&D appealed more to boys than to girls: it just wasn’t written with girls in mind. But I hope you can also see a good reason why boys might have found it interesting: not only, DM willing, did you get to meet harlots; you got to meet words. I don’t think I knew what a panderer was before I read the Dungeon Master’s Guide, not to mention a dweomer or a geas, words that Gygax more or less introduced into modern English. Look them up.

6. When players want to conjure up the atmosphere of the game, they often do so by reference to a widely-known or infamous rule. Consider, for example, the T-shirts sold to gamers, which read, “JESUS SAVES / EVERYONE ELSE TAKES FULL DAMAGE,” a reference to the “saving throw,” the die roll a player must make to determine if he is affected by poison, magic, dragon’s breath, etc. (Not to mention the even more obscure “JESUS SAVES / EXCEPT ON A NATURAL 1,” which I won’t get into here.)

7. Note for non–war gamers: Until computer games came along, there were two main kinds of war game: board games and miniatures games. Board games, as their name implies, are played on a board, with plastic or cardboard counters. Miniatures games are played with miniature soldiers (or tanks, or elephants, or what have you) on a sand table or some other model terrain. Miniatures gamers tend to look down on board gamers, who can’t achieve as high a degree of historical accuracy as the miniatures gamers can. Board gamers, on the other hand, tend to regard miniatures gamers as fussy collectors.

8 Basements keep coming up in the story of D&D. I wonder if the dungeons where most early adventures took place are fantasy versions of the basements of the Midwest?

9 Imagine simulating a long siege, e.g.

10 Gygax made similar modifications to the game: “After a while, though, the guys got tired of playing. I decided one day that we were going to play a little variation of medieval combat. I secretly told one side, ‘OK, you guys have a wizard in your group and here’s what he can do: he can throw a fireball,’” etc.

11 See note 8, above.

12 This is classic cave-speak. Fifth-level refers to the notion of experience levels, which are based on experience points (see above). A fifth-level elf kicks more ass than a newly-created first-level elf, but considerably less ass than a superheroic eighteenth-level elf. +2 sword denotes a magic sword, which gets a bonus of 2 on its dice rolls to hit a foe, and to do damage.

13 Not everyone is drawn to the role-playing aspect of Dungeons & Dragons. Glenn Blacow, in an article called “Aspects of Adventure Gaming,” describes four types of gamers, a taxonomy which has come to be known as the “Fourfold Way.” The types are: wargamers (who seek to dominate the game by means of superior strategy), “power gamers” (who seek to dominate the game by exploiting the rules to maximize their characters’ power), role-players (for whom character is paramount), and storytellers (who get their kicks from the narrative aspect of the game). Of these groups, however, only the war gamers may be immune to the pleasure of being someone else—and even they must have some sense that their characters are kewl.

14 Strangely, these seem to be more or less acceptable behaviors in the real world circa 2006, which raises an interesting question: was D&D uncool because it catered to people who liked to express their aggression and greed in fantasy, rather than in reality? Or has the world become more like D&D?

15 Level 1-4 readers may now recall another category of adventures, exemplified by the horrifically difficult Tomb of Horrors: those adventures in which few monsters could be destroyed, and your goal was mainly to keep the monsters from destroying you.

16 In a public Minneapolis gaming group, if you’re curious.

17 And this is to say nothing of the player whom Fine observes playing Empire of the Petal Throne, another fantasy role-playing game published by TSR:

Later in the game, when we meet another group of Avanthe priestess-warriors, Tom comments: “No fucking women in a blue dress [sic] are going to scare me…. I’ll fight. They’ll all be dead men.

JACK: Men?

ROGER: Is that your definition of a woman, a dead man?

TOM: A dead man.

It’s hard to know what to make of this, but the phrase castration anxiety certainly comes to mind.

18 Chick Ministries being, of course, the fundamentalist Protestant group responsible for all those tracts in cartoon form: there’s one about the end of the world, and one about how the Jews are going to hell, and, yes, there’s one about role-playing games.

19 Schnoebelen also reports that in the late 1970s, two TSR employees came to speak with him in his capacity as a Satanist, to make sure the rituals in the game were authentic. “For the most part,” he assures us, “they are.” This assertion must have alarmed people who had never read the D&D rulebooks, in which, to the best of my knowledge, no rituals are described. Nor do I remember a player ever “saying” a spell. Mostly people said, “I zap the troll with a fireball,” or, “Let’s see if my sleep spell will work on these orcs.”

20 The theorist in question is Christopher I. Lehrich; his essay, “Ritual Discourse in Role-Playing Games,” can be found at http://www. indie-rpgs.com/_articles/ritual_discourse_ in_RPGs.html. Specifically, Lehrich says, D&D is like a rite of passage by which a boy is inducted into manhood: the boy is removed from his familiar surroundings; he is made to wear strange costumes and utter strange sounds; at ritual’s end he is received into the community in his new status. Actually, it might make more sense to think of D&D as an anti-manhood ceremony: having undergone trials by rules and by role-playing, the initiate is guaranteed immunity from growing up. 21 Even nominally evil player characters (see §3.0) often cooperate; they do their evil only to the non-player characters, who aren’t in a position to resent them when the game is over. As Skip Williams, who for many years wrote the “Sage Advice” column in Dragon, a D&D magazine, puts it, “evil characters tend not to act like evil people in real life. It’s more of a hat you wear.”

22 Not unlike the New Games, which emerged circa 1966 as a mode of resistance to the Vietnam War (which was a “game” conditioned by the zero-sum mentality of the Cold War, but which, in the instance, both sides seemed to be losing), and persist as a way of encouraging kids to think cooperatively. It’s a pity that New Games are even less cool than D&D these days. 23 The resemblance of this description, to, say, an old-school rave, experienced by a person or persons under the influence of Ecstasy, is not unintentional. Actually, a rave is one of the few things I know of that’s as massively and necessarily cooperative—and as fun—as a really good game of D&D.

24 For the long version of this story, see the Scenario, below.

25 Connors was speaking to Monte Cook, a designer who has interviewed many of the TSR personnel. The interviews are available at monte cook.com, an invaluable resource for anyone who wants to know more about the history of Dungeons & Dragons.

26 I.e., a game where people act out their characters theatrically: costumes and running around are often involved.

27 One female gamer reports, “I have been a player in an all-female game where we spent all session shopping.” Is that a Prada Cloak of Disappearing?

28 Note to Level 3-4 Readers: It turns out that Gen Con predates Dungeons & Dragons; in fact, Gygax and Dave Arneson met for the first time at Gen Con 2, in 1969.

29 Among these dishes was the Cthulhu Calamari, which I have to confess I ordered. It turned out to be a half-sized portion of rubbery deep-fried squid in an oversweet sauce: one of the worst foods I’ve ever eaten, which, I guess, serves me right.

30 Also, I got sucked into a game of Call of Cthulhu, a role-playing game set in the universe of horror writer H. P. Lovecraft. This is basically another story, but as I may not have the chance to tell it in print elsewhere, I will note that in one round of the game, we role-played the highest echelon of the current administration: Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Rice, Porter Goss and Michael Chertoff. The really eerie thing about this round was how plausible it all seemed, even when we were herded into a bunker where Cheney shot Bush and Rice and Rumsfeld, and I shot Cheney, and Cheney shot me. (Goss had already committed suicide under mysterious circumstances.) It could happen, I tell you.

31 Like graph paper, but printed with hexagons instead of squares. Commonly used for large-area and wilderness maps.

32 Well, Gygax and Arneson, anyway. But Gygax’s has always been the name to conjure with. Perhaps because it’s such an excellent name: Gygax. It sounds alien, as though E. Gary Gygax were the point of tangency between the ordinary world and the world of dragons and magic. (Actually, it turns out that Gygax is a Swiss name. It comes, Gygax says, from the Latin, gigantus, meaning “gigantic,” which suggests that Gygax’s ancestors must have been extraordinarily large. Gary Gygax himself is only 5’11”, so either the race has fallen off, or he’s telling me tall tales. Which, in fact, he has a habit of doing; maybe that’s what gigantus really refers to. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

33 Note to Level 3-4 Readers: For a portrait of the youthful E. Gary Gygax, consider the cover of the original Players Handbook. The face of the thief who’s prising a gem from the eye of the idol is Gygax. Actually, the thief who’s helping him is Gygax, too, and so is the fighter cleaning his two-handed sword in the lower foreground, and so are all the people on the back cover. Apparently the artist, D. A. Trampier, wasn’t good with faces; he learned how to draw Gygax and stopped there.

34 Note to Level 1-4 Readers: From which D&D essentials like armor class and hit points are derived.

35 My copy of the Monster Manual, one of the contested volumes, reads “By Gary Gygax” on the cover.

36 Which didn’t stop him from recruiting Welles to play the villain in the Dungeons & Dragons movie, a part which Welles apparently accepted. If only Welles had lived a little longer, and the movie had been made, instead of the dismal D&D movie that was made in 2000, starring, mysteriously, Jeremy Irons and Thora Birch.

37 The same wife who was dismayed to find Wayne and me sitting on her porch early one Saturday morning. About halfway through our interview, she came out of the house again and asked, incredulously, “Is he still talking?” He was. “He doesn’t have that much to say!” she exclaimed, and left without another word.

38 Unearthed Arcana, if you’re wondering. The book is a miscellany of rules, spells, and character classes; it introduced the gnome race, the seldom-played cavalier and the beloved barbarian to the game, along with spells like Withdraw, Banish, and Invisibility to Undead, which may or may not have expressed Gygax’s feelings towards the Blumes.

39 And indeed: while Wayne and I were talking to Gygax, his son Luke called to say that he was moving to Monterey, CA, which prompted Gygax to list some places where he would have liked to live—New Orleans, San Luis Obispo—“But I said, fuck ’em, they won’t let you smoke, and, land of fruits and nuts, bah.” He concluded, “You know I’d still be up there on top of Summit Ridge Drive if it was my choice.”

40 The decision to keep fighting Gygax must have made business sense, but when you look at how much it cost TSR, and how little the company gained by it, in the long run, their victory seems Pyrrhic. For the company, at least: Williams says she did fine by the sale of TSR in 1997, and her brother Flint suspects that she came out ahead. Which makes her the winner in this story, I guess, by any real standard.

41 We acted out the illusion, waving our arms and making lobster noises, which alarmed Gygax.

Thanks to Michelle Vuckovich and Jennifer Estaris for their help researching this article, and of course to Wayne, for being a part of it.