It may come as no surprise to many that former president George W. Bush’s favorite writing utensil while in office was not a special ballpoint pen, probably the most common writing utensil in the world today, or even a fountain pen, that symbol of old-school sophistication. It was a black Sharpie marker. According to a Bush insider, the former president would ask for his markers by name, “and if someone hands him something else, he barks, ‘Where’s the Sharpie?’” The Bush Sharpies actually carried his signature and the white house printed on the side. He reportedly even had special camp david Sharpies.

What makes Bush’s choice of writing utensil so appropriate has less to do with what he communicated in writing than with what many believe he failed to communicate. For a presidential regime marked by excessive government secrecy and restrictions on information flow, it is only fitting that a thick black marker would be central to the administration. As one source inside the White House explained, the president’s gift package for all new aides included a signed golf ball and baseball, a tie clip, cuff links, and the set of the presidential black Sharpies. All the better, we might presume, to black out inconvenient facts the administration didn’t want the public to see.

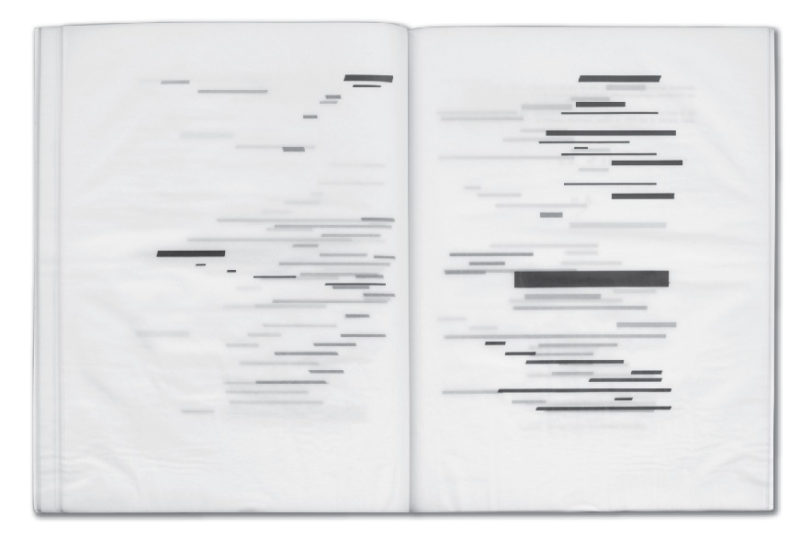

While many other critics have already laid out the problem with the Bush administration’s overbearing secrecy policies—President Obama not the least of them—what draws my attention is not the battle between Republicans and Democrats, but those infamous black marks found on government documents and the process, called “redaction,” of how they get there. Beyond their most obvious function—namely, to cover up words deemed confidential—black marks have actually created a system of unintended signals and interpretations. Unlike the pen, a symbol of free thought’s transparent expression, or the sword, a symbol of free thought’s oppression, the black marker of government secrecy exists somewhere between these two places. It certainly obscures, but it manages to explain something, too.

While the literal act of redaction attempts to extract information and eradicate meaning, the black marker actually transforms the way we read these documents, sparking curiosity and often stirring skeptical, critical, and even cynical readings. As redacted government documents make their way from government bureaus into the hands of citizens, a peculiar transformation seems to take place, one that seems to create a paranoia within reason. Based on all we know about government cover-ups over the course of the twentieth and twenty-first century, and especially since Watergate, it is understandable that people would be somewhat paranoid in their interpretations of the motivations behind government secrecy. Bad things really have...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in