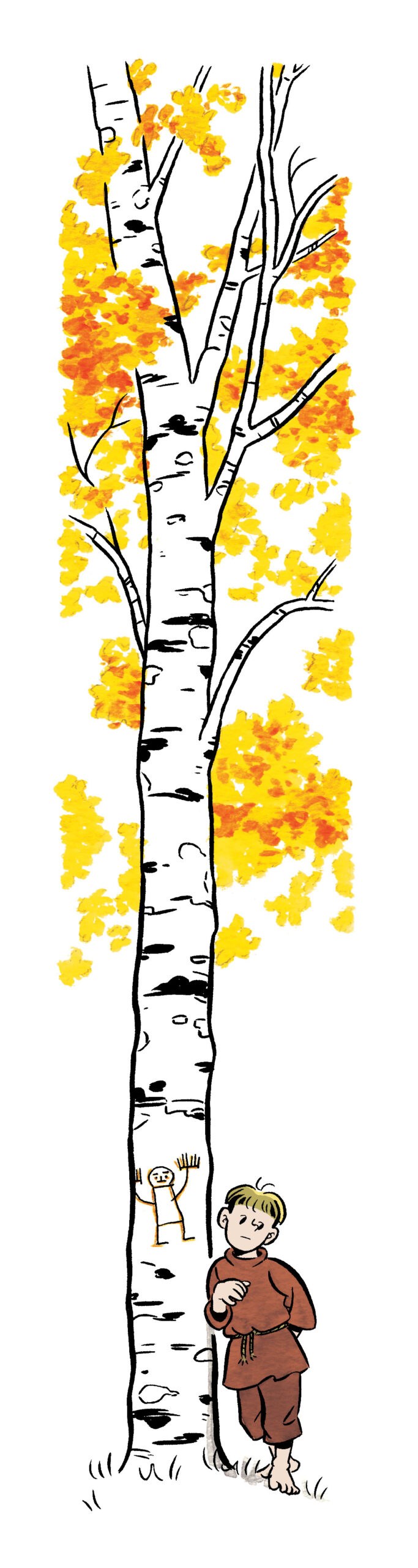

In the city of Novgorod, in the thirteenth century, a seven-year-old named Onfim drew mythical creatures on birchbark. Nothing about Onfim’s drawings are world-shattering. That is why I love them. He was a little boy, living in what is present-day Russia, who grew bored of his school assignments. His self-portraits look a bit like tadpoles or perhaps Mr. Potato Head, like the people I drew as a kid (and you probably did too): smiling ovals with sticks for limbs and a random smattering of fingers. It’s the same style of drawing you see affixed to fridges or drawn on the sidewalk in chalk. They are a developmental rite of passage and endearingly human.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in