For more than forty years, Charles Johnson has been a fixture on the literary scene in Seattle, along with two other African American writers, both transplants: the late Octavia Butler and the late August Wilson. Like they did, Johnson has produced work his own way, avoiding the expectations that many would impose on a Black writer. This journey of distinction for Johnson began in 1982, with his second published novel, Oxherding Tale, a quasi–slave narrative and rogue’s narrative steeped in both Eastern and Western philosophy. Johnson has since published twenty books, and has received numerous accolades for his work, including the National Book Award for Fiction for his novel Middle Passage, a MacArthur Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Born in 1948, Johnson grew up in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, home of Northwestern University. He first came to prominence as a political cartoonist and illustrator when he was still a teenager: At the age of fifteen, he was a student of cartoonist and mystery writer Lawrence Lariar’s. In 1969, he attended a lecture by Amiri Baraka, which inspired him to draw a collection of racial satire titled Black Humor, which was published by Johnson Publishing Company, the publisher of the widely read magazines Ebony and Jet. A second collection of political satire, Half-Past Nation-Time, was published by Aware Press in 1972. During this period, Johnson earned a BS degree in journalism at Southern Illinois University. He then went on to earn his MA in philosophy at the same university, while taking fiction-writing classes with the legendary John Gardner. In 1976, Johnson joined the faculty in the Department of English at the University of Washington, where he taught until his retirement in 2009.

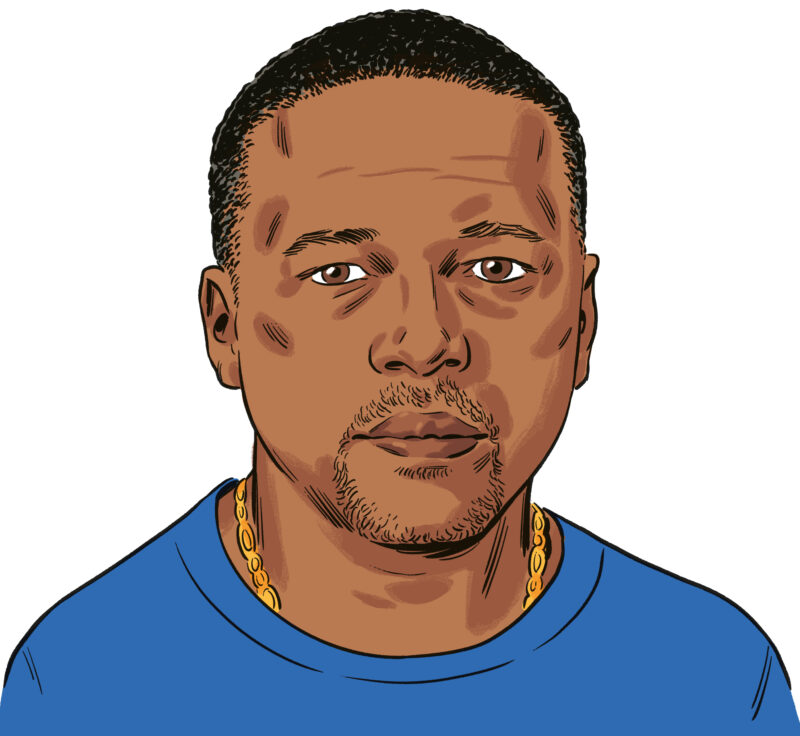

I sat down with Johnson on a mild afternoon at Third Place Books in Seattle’s Ravenna neighborhood, not far from Johnson’s home. To take advantage of the weather, we opted for an outside table, where we enjoyed good coffee, good food, and good conversation. Preferring the nickname Chuck, Johnson is confident but humble and soft-spoken; his eyes sparkled with intelligence. He keeps his hair in a short Afro, completely gray, with a well-groomed halter-like connected beard, also gray. As we spoke, I observed something of the scholar about him, in the way that his spectacles dangled against his chest from an elastic cord encircling his neck.

—Jeffery Renard Allen

I. TWIN TIGERS

THE BELIEVER: How do you define yourself as a writer?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I don’t call myself a writer. One of my books is titled I Call Myself an Artist.

BLVR: So you’re an artist?

CJ: Yes.

BLVR: I’m going to phrase the question differently. Would you call yourself an experimental writer in the usual sense of whatever that term means: someone seeking to innovate, break rules?

CJ: I’m a philosophical writer because my background is in philosophy. I work with different forms and genres to realize, I hope, fiction that is philosophically engaging and capable of transforming our perception in some way. As for experimentation, Clarence Major—he’s an experimental writer. And Ishmael Reed is as well. I’m not an experimental writer. The thing about it, too, is I started out as a cartoonist, as a visual artist and journalist. When I was in my teens, drawing was my first passion. Still is to a large extent. So I’ll say I’m an artist. Today I might be doing visual art. Tomorrow I might be doing literary art. Last night I got together with some old buddies for Wednesday-night martial arts class. We’ve been doing this since 1981, training together, every Wednesday night. As an artist, there are different ways to express myself.

BLVR: You see martial arts as a form of self-expression?

CJ: It is. Well, when I was young, back in my teens, it seemed to me reasonable that I needed to develop myself in three areas, to the best of my ability. One was mind, one was body, one was spirit. For mind, I chose philosophy, which seduced me when I was an eighteen-year-old undergraduate at Southern Illinois University. Even though I was a journalism major, I stayed on and got my master’s in philosophy. And then I kept going until I got my PhD in philosophy at Stony Brook University. So that was for mind. For body, I chose martial arts when I was nineteen. My first dojo was in Chicago, and was a little like a monastery. I began working out there, without knowing anything about the world of martial arts. It was a cult in the sense that the members of the school blindly followed the leader, but I didn’t know it. This was during the time of the Chicago Dojo Wars, as they were called. My school was in competition with another school, run by a flamboyant guy who called himself Count Dante. Count Dante. You’d see him sometimes in the martial arts magazines. [Laughing] I don’t know anything about his system or his style, but I do know that somebody from his school came by our school one night to invite us to participate in a tournament. He was really arrogant. He said, If you think you’re up to it, you can come try out in our tournament. Our master wasn’t there that night, but when he found out, he told all of us, Somebody comes in like that again, tell them to leave. They don’t leave, you go over here to the wall and take down a weapon. Give one to him and you take one. Now, these were traditional weapons, Chinese weapons, you know—spears and staffs and swords. And if he won’t leave, kill him. I’m thinking, What? He’s telling us to kill. He said killing was within our rights when somebody invaded our space and we gave them fair warning. It was a rough school. I thought some nights I’d die in there, but I stuck with it until I got my first promotion. Southern Illinois University was about six hours away. I couldn’t keep up at that dojo, but I continued with karate on campus. I went through three karate systems, you know, and then settled on Choy Lee Fut kung fu in 1981 when I went down to San Francisco to work on a Black PBS TV show called Up and Coming. Wherever I lived, I always looked for a school to train at.

When I came out this way, I discovered there were branches of the Choy Lee Fut school, one here in Seattle and one over in Bremerton. I was able to continue training here in Seattle until the one school here closed. After it closed, our teacher, Grandmaster Doc-Fai Wong, gave me and a buddy permission to start classes in Seattle. He gave us the name Twin Tigers. We taught for ten years. My buddy passed away a couple of years ago, but I still get together with a couple of old friends on Wednesday nights. We go through our empty-hand sets. Then we go through our weapons sets so we don’t forget them. Choy Lee Fut has over 130 sets because it combines three martial arts lineages, one from Mr. Choy, one from Mr. Lee, and another one from Chan Yuen-Woo, who taught Fut Gar. Choy Lee Fut is one of the old Shaolin monastery fighting systems.

So mind, body, and spirit. For spirit I chose Buddhadharma. Buddhadharma, for training and cultivating the spirit. I was born a cradle Christian, and I still am to a degree. But the Buddhadharma offered something that was good for me when I was young.

BLVR: How old were you when you were introduced to Buddhism?

CJ: Fourteen.

BLVR: And how did it happen?

CJ: Back then, my mother was an avid reader and a member of three book clubs. One of the books that came into the house was on yoga. I read a chapter on meditation and afterward I told myself, Let me see what this is like. For half an hour, I practiced the method of meditation described in this chapter. It was amazing. My consciousness changed during that half hour of focusing. I’d never done that before, and the experience affected me for life. It made me more conscious of the operations of my own mind and it also made me have more compassion for people around me, more empathy. I began to approach the study of Buddhism and other Eastern philosophies in a scholarly way and read everything I possibly could. As both an undergraduate and a graduate student, I took courses in Hinduism and Taoism.

BLVR: That was back in the ’60s?

CJ: Yes, back then, when there was all kinds of stuff floating around.

BLVR: You mean people like Alan Watts?

CJ: Yes, Alan Watts. And D. T. Suzuki was very important at the time because he interpreted Japanese Zen for a Western audience. He did it in a particular way to make it intellectually interesting to academics. Something I didn’t care for was what I call “fuzzy-bunny Buddhism,” the feel-good stuff. With Buddhism, you must get it right. It’s not any old thing you make it out to be.

Buddhism grows and evolves in every country it goes to. It has a particular flavor here in America, because Americans are very interested in politics and social justice. I think this is because we draw on Christianity’s emphasis on the social gospel about changing the world that had such an impact on Martin Luther King Jr. So there is that quality to the American Buddhist convert community.

BLVR: What impact has Buddhism had on literature in our country?

CJ: There’s very little written about the spiritual register in our literature, especially in fiction. Truth to tell, I don’t know American poetry as well as I know the fiction.

BLVR: In terms of my question, I’m thinking about two aspects of American fiction: the tradition that deals with spiritual questions, and the tradition that deals with philosophical questions. Would you say there’s also a lack in terms of philosophical fiction?

CJ: Going all the way back to the nineteenth century, Americans have been anti-intellectual, very suspicious of intellectuals, particularly of European intellectuals. The emphasis is on the common man, so to speak, right? You see that bias starting with Jefferson in the eighteenth century. The century that followed gave us philosophically interesting writers like Hawthorne, Melville, and Emerson the transcendentalist. But then something happens around the turn of the twentieth century with the rise of naturalism. Our writers become less philosophical and less focused on the spiritual register. Part of that has to do with the fact that naturalism in fiction is a subset of naturalism in science and sociology. Naturalism does not involve spiritual experiences. Of course, naturalism offers a deterministic view of the world. Biology, the environment, cause and effect—that’s all that really matters in the naturalistic orientation.

I think there’s more to human experience—and that experience is much, much larger than that.

In the twentieth century we don’t have much in the way of a spiritual/philosophical register in American fiction. William Gass, a trained and important philosopher, was one such writer. My former teacher John Gardner wasn’t a trained philosopher, but he explored ideas like Sartrean existentialism in his novel Grendel.

And then among Black writers I would say that Jean Toomer is philosophically interesting. Toomer was a follower of Gurdjieff. I wrote a preface for Toomer’s collection of aphorisms, Essentials, which was edited by the late Rudolph Byrd. Richard Wright is also interesting, even if he was largely a Marxist thinker.

BLVR: I would argue that Wright became an existentialist.

CJ: He was by the time he moved to France. Of course, over there he hung out with Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. And he started getting into phenomenology. He owned a copy of a philosophical work by the founder of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl. I read, in fact, that he worked with it so much he had to get another cover for it because it was falling apart.

Ralph Ellison is also worthy of attention as a philosophical writer. In Invisible Man he addresses Marxism and existentialism, then plays on Freud, and so forth.

BLVR: Ellison seems to define the idea of race and racism as ultimately absurdist in an existentialist sense.

CJ: His novel is absurdist. Those writers to me are the ones I found to have a philosophical kind of register. Still not, though, a spiritual register. Not in Wright, not in Ellison. Only in Toomer.

II. A BIRD IN THE BUSH

BLVR: Please talk some about how you became interested in writing fiction.

CJ: Well, I didn’t enjoy journalism, since I wanted to be in philosophy instead. However, it was good training. Before World War II, how did writers learn their craft? They learned it from newspapers, for the most part. I was also an avid reader because stories fed my imagination as a cartoonist and illustrator. When I was in high school, I made a point of reading a book a week, outside of class, and then sometimes it would be two books a week. Another week it might be three books. By the end of my freshman year of college, I still thought I wasn’t reading enough.

BLVR: What years were you in college?

CJ: I started in ’66, and I graduated in ’71. I took an extra, fifth year because I was doing all these philosophy courses while doing my bachelor’s degree in journalism. And then two years for a master’s degree in philosophy, and then three years at Stony Brook for the PhD.

The interesting thing about that period, of course, is that it was during the time of the Black Power movement and the Black Arts movement.

BLVR: Did you have any involvement with any of those Black Power or Black Arts movement groups, like OBAC [the Organization of Black American Culture], in Chicago?

CJ: I was not involved with any group, although I had a couple of friends who were Black Panthers, including a poet friend of mine named Alicia. For a time, I became Marxist, from ’71 to maybe ’73. My master’s degree was a study of Wilhelm Reich as influenced by Marx and Freud. But I was not involved in the Black Arts. Again, I was a journalist and a cartoonist. I didn’t know many writers or poets. Those were not the people I was hanging out with. However, in 1970, when I was twenty-two, I decided to write a novel about the martial arts kwoon I had gone to in Chicago, Chi Tao Chuan of the Monastery. That first novel was called “The Last Liberation.” I wrote the book over the summer.

BLVR: You never published that one.

CJ: It was a learning novel, because then I wrote five more novels in two years, teaching myself what I hadn’t known in the previous book for the next book. One of those books was an early version of The Middle Passage. I started the research when I was still an undergraduate, because there were essentially no Black teachers at Southern Illinois University. However, a Black visiting professor came from St. Louis and taught a course, and I took it. I asked him if I could do my research on the Atlantic slave trade, and he told me I could. But I wasn’t ready to write the novel yet, because I hadn’t immersed myself in fiction enough.

Around that time, Black graduate students formed the first survey course on Black history at Southern Illinois University. And one of my friends, Thomas Slaughter, a graduate student in philosophy, and some other Black students brought Amiri Baraka to campus. I was one of ten undergraduates who Tom selected to be discussion-group leaders. For the past year or so, I had been avidly reading everything I could about Black history and culture. Then one time in my discussion group, one of the grad students in history was lecturing on the Middle Passage. I remember sitting in this big auditorium when he put up that cross-section of the slave ship with dozens of the slaves arranged in spoon fashion. That burned itself into my mind. I hadn’t seen an image this startling before. So when the visiting Black professor came from St. Louis, I did some research under his direction.

BLVR: How did you develop as a writer?

CJ: By the time I started my seventh book, Faith and the Good Thing, I had taught myself everything I could about writing fiction. One novel I finished was called “Youngblood” and it was about a Black musician. I had a friend who was a musician, and he taught me how to play the piano for this novel. That book was accepted for publication with a start-up publisher in New York. By that time, however, I had started working on Faith, with John Gardner looking over my shoulder. I remember I said to him, “Look, I have three chapters of this book, and I don’t know if I can finish it, but it’s radically different from the other six books I’ve written.” The other six were all naturalistic, because I was reading Baldwin, John A. Williams, Richard Wright, and other writers like that. But with Faith and the Good Thing, I got to a place where I could write a philosophical book. It’s a tale, a total break from the other books.

I asked Gardner, “What should I do? Should I let them publish ‘Youngblood’?” The publisher liked the book because it reminded them of Baldwin. Well, I’m not Baldwin. I was developing my own vision. Gardner said something very wise. He said, If you feel you’re gonna have to climb over it later, don’t publish it. So I wrote them. I said, “I’m sorry, but I don’t want to publish the novel.” That was like a bird in the hand as opposed to, you know, one in the bush here. I didn’t know if I could finish Faith, but I did. Gardner got me his agent and it came out a year later. I wrote it in nine months.

The other six books I wrote in ten weeks, one every ten weeks for two years. Faith I spent nine months on. I thought it was a long period of time to spend on anything, but I learned better after that, because with the next novel, Oxherding Tale, I began to see what was at stake.

When you set out to do something, and you’re a literary writer, you have to recognize that this book could be your last will and testament in language. Every book of fiction I’ve done has transformed me in some way, from the research to the writing. You write trying to get it right, not for fame and fortune. The novel is a form of communication through the best technique and the best thought and feeling that I can bring to bear. Oxherding Tale took five years to write. Middle Passage took six years. Dreamer took seven. Each book is the best I can give in terms of whatever I’ve learned in the way of craft, human experience. That’s why art matters.

III. “JACK KIRBY WAS MY HERO”

BLVR: Tell me about how you started publishing your comics.

CJ: My freshman year at Southern Illinois University, I sold six scripts to Charlton Comics. I took the stories I had done in high school and turned those into one-page comics. And they bought them, although they didn’t have me illustrate them, because they had an in-house illustrator. I was seventeen years old. I had finished a correspondence course with Lawrence Lariar when I fifteen years old and still in high school. He was a well-known cartoon editor at the time.

Around that time, one of my buddies was doing catalog illustrations for a magic company in Chicago. So I said, “Well, I’m going to work for this guy.” I went and showed him my drawings from high school, and I got a job. They paid me to draw six magic tricks for their catalog. I still have that first dollar. I framed it. It’s in my study right now. Because that’s the day I got paid to do art. See, my passion as a cartoonist was to publish as much as I could, wherever I could. You know how churches put out a mimeographed bulletin for members? I went and talked to whoever did that at my church. I said, “Let me do one of those.” They did. I looked for every opportunity, because I wanted to see my work in print. That was the main thing.

When I started college, I went right to the campus newspaper, The Daily Egyptian, showed them my swatch. I went on to draw hundreds of cartoons for them. I did everything. I even drew illustrations for ads. Then I went up to the town paper, The Southern Illinoisan, showed them my swatch, and I started doing editorial cartoons for them. My mindset as a cartoonist was to sell my work anyplace I could. Cartoons are not a way to make a living, not unless you get a syndicated strip, which is rare. But money didn’t become a serious issue for me until I had a kid and had to support a family.

BLVR: Because Afrofuturism is a trend, there’s been a lot of interest in going back and looking at Black cartoons. I remember reading things like Luke Cage, Green Lantern, and Black Panther as a kid in the ’60s and ’70s.

CJ: That was ’66. That was the first issue. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby created the Black Panther for an issue of The Fantastic Four. I remember the year, because that was the same year I went off to college. I was reading all the Marvel comics and collecting them. I know they’d be worth a fortune now, those original issues, and I have few that are in mint condition. But I had started collecting comics in the ’50s.

BLVR: Did those cartoons make any impression on you?

CJ: Oh, Jack Kirby was my hero. I started reading his comics in ’55 when I was seven years old. What he did was like nobody else, and he was prolific. Everything that guy did—from the late ’30s all the way up to maybe the ’90s, when he died—is amazing. As I see it, his best period was from about ’55 to ’65. He worked everywhere and for everybody. He had to go to war. He came back. He did many years of romance comics. He had his own comics company at one point. But then around ’65, he started to repeat imagery, started drawing the same thing over and over.

BLVR: You grew up in the ’50s, while I grew up in the ’60s, and many people in the Black community today think we lived in the Dark Ages. I’m getting into one of my pet peeves. There is a kind of simplistic assumption that there were few Black comics when we grew up, and no Black science fiction, because there weren’t Black people in comics or science fiction. Because of this lack of representation, we couldn’t imagine ourselves in those spaces. Correct me if I’m wrong, but my impression is that you don’t feel you suffered a limitation.

CJ: No, I didn’t. When I would read literature or comics, I would be with the characters. They didn’t have to be Black for me to relate to them. Now, if I came across something racist that pulled me out of the story, I’d have to stand back and look at it. But you’re going to find that, unfortunately, with just about every American writer.

BLVR: Or British, for that matter.

CJ: Yes, the British. You see racist imagery sometimes, even in comics. It’s there in the ’40s. It’s there in animated films in the ’40s, Disney and Warner Bros. It’s just part of American culture, white American culture. Now, we don’t want to show these things today, because we’re embarrassed by them. But they exist. I saw them. I grew up with them, but this didn’t stop my passion for creating.

IV. “THE GOOD, THE TRUE, AND THE BEAUTIFUL”

BLVR: You studied with John Gardner when you were a graduate student at Southern Illinois University. What strikes you now about him as a teacher?

CJ: On the one hand, he was remarkable. On the other, he had his limitations.

BLVR: Please explain.

CJ: He was the best creative-writing teacher we had in the country. He produced three important books on the subject: The Art of Fiction, On Becoming a Novelist, and On Moral Fiction.

I used The Art of Fiction for thirty-three years at UW. Every quarter, I had my students do the exercises in the back of that book. Gardner sent me those questions before the book was published, as soon as he learned I was going to teach. The book was still unfinished when Gardner died. It was brought together by our friend Nicholas Delbanco, who directed the writing program at the University of Michigan.

BLVR: He was also one of Gardner’s students.

CJ: Gardner introduced me to Nick, saying, “You two are the best young writers in America. You should know each other.”

BLVR: You said earlier that Gardner had some limitations.

CJ: Yes. Gardner was very Western, very white. I mean, we eventually parted ways as student and teacher. He was good with his comments for me on Faith and the Good Thing, but he did not support Oxherding Tale at first, because he did not understand it. There was a resistance to Buddhism. He sent me a letter where he wrote, If Buddhism is right, then I’ve lived my life wrong, and I refuse to believe that. Yet just before the book’s publication he volunteered himself to write a blurb that says, “A true storyteller… Oxherding Tale is a ‘classic’ in the noblest sense.”

BLVR: There it is.

CJ: He was initially responding to the novel, not in terms of craft, but rather in terms of a personal issue that he had with Buddhadharma and probably a fear of it as well. He could not understand that his way of looking at and experiencing the world was not the only way. And the publishing industry at that time largely shared his perspective. I didn’t know that the book would be rejected two dozen times, like Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. For many Westerners, this is a book they cannot easily wrap their minds around. But my feeling about art is that it changes your perceptions. It will help you to see something that you’ve never seen before within the limited world you have been in.

BLVR: Did you work with any other creative-writing teachers when you were in college?

CJ: No. I’m a philosopher, so there was no way I was going to take a philosophical manuscript into the kind of creative-writing classes you had in the ’70s. Interestingly enough, Gardner was described as a philosophical writer when he published The Sunlight Dialogues. I was at his farmhouse one Christmas when he showed me the book. He had just gotten copies of it. Grendel had been critically acclaimed, but The Sunlight Dialogues would be his first bestseller. For ten years he was like a comet across the literary landscape. The hardest-working writer I think I’ve ever seen, and generous toward his students.

BLVR: How do you feel about the position that Gardner takes in On Moral Fiction when he argues that experimental fiction is immoral? He argues that fiction should be about what he calls “the Good, the True, and the Beautiful.”

CJ: I believe fiercely in “the Good, the True, and the Beautiful.” I wrote a response to Gardner’s book called “A Phenomenology of On Moral Fiction.” As I argue in that piece, “responsible fiction” would have been a better title for John’s concerns. Permit me this analogy. No matter how bad the world is, as a parent you’re not going to tell your kids that the odds are stacked against them. Instead, you have to give them, despite all the negativity, a sense of hope and personal agency. There are always counterexamples of heroism, survival, and resilience. That is what I mean by responsible fiction. I will never write a book that offers no hope. By every metric, America right now is trending down in too many ways, on the decline. Whether it’s the quality of life, the state of education, the teacher shortage, homelessness, or, in a place like Chicago, where you and I come from, the gangs, the relentless killings. However, it would be immoral for you as a writer to dump all that negativity on the reader. You can write about bad shit happening all day long and it’s just bad shit happening all day long. I don’t need to contribute to that.

BLVR: Are there subjects you won’t write about?

CJ: I don’t like writing about slavery. If you’re going to be honest to your characters, you have to be those people, imaginatively. You have to project yourself thoroughly and fully into them, like I tried to do in my stories for the history book Africans in America, a companion volume to the PBS series produced by WGBH in Boston. I wrote twelve stories for that book, every one about a slave. They wanted me to do twelve stories that would dramatize the historical record and let viewers know what it felt like to be a slave or a master. To do that, you have to be these characters, and that means you have to experience their pain and you have to experience their hatred, sometimes even murderous hatred. You have to inhabit the heart and soul of your character. If that character is good, then you’ve got to be good. If that character is evil, then you’ve got to be evil. Every fiction writer knows this. You are every performer on the stage of the page. At least that’s what I’ve experienced. I put off writing the stories until the last minute. I wrote them all in a month, three a week, just to get it all done and out of my system. However, I still carry scar tissue from that experience.

America right now is suffering from a massive mental health crisis. You read about it every time you open a newspaper. It’s good that people are talking about the issue, that they’re not ashamed. However, as a Buddhist, I feel we have to have a spiritual practice that allows us to get rid of the sewage in our spirits that we may have picked up in our childhood or early in life or through our bad experiences and conditioning. For this reason, I don’t like to take on those assignments that will require me to dwell on ill will, hatred, or evil, because if we dwell on those things, they get into our minds and hearts and can do serious damage. I like to “accentuate the positive,” as the song used to say. And my Buddhist practice allows me to cleanse away the grit and grime.

V. “SMELL THE TRUTH”

BLVR: As a writer, do you consciously see yourself as working in a tradition? Do you see yourself as an African American working in an African American tradition? Or as a Chicago writer? A Seattle writer?

CJ: I don’t like labels. I don’t like boxes. When I was starting out as a writer, I wanted to contribute to the very small tradition of American philosophical fiction. That’s why I got a doctorate in philosophy, to know Western intellectual history front to back. Then I needed to know more—namely, the tradition of Eastern philosophy. We all have to develop our own individual vision. And it seems to me that critics often don’t know what to make of us, we writers and other artists. Sometimes I think that artists are too complex for some critics. I have had six books published about my work, but only three out of the six are good.

Critics talk about a writer only in terms of what they know and understand. If you don’t know anything about Eastern philosophy, then you can’t address that aspect of a writer’s work. Or if you don’t know anything about cartoons, how can you examine me as a cartoonist?

BLVR: Do you think that someone who doesn’t know your comics but discovers them will then have a different perspective when they go back to your fiction?

CJ: Jonathan Little published the first critical book about my work, a book called Charles Johnson’s Spiritual Imagination. He looks at how my comic art influences my fiction, including in Oxherding Tale. I really love the book The Writer’s Brush: Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture by Writers. Many writers are more than just writers. I’ve fought my entire life against ideas, labels, and situations that try to limit me, because I think our talent is God-given.

The Writer’s Brush is good because what it tells us is that an individual may wake up one day and decide, Let me work on a short story. And the next day you may wake up and think, I’m really interested in the mind-body problem. Let me write a philosophical response to or essay about that. Or you might wake up and think, I want to do a sketch or a drawing. It’s all part of the same global talent within an individual. It’s a way of being in the world.

BLVR: I have not heard you say anything about music.

CJ: That’s not my orientation. My orientation is sight, although of course I love music. When I write fiction, it’s my visual imagination that goes into the description. I like detail. Strong, bold outlines. Even in writing I like composition and I think about foreground and background. That’s my visual imagination. I have to work hard at getting in the other senses—smell, sound, taste, and touch. Though we have five senses, we tend to be sight-dominated in the West. We always say, Oh, I see the truth. We don’t say, I smell the truth. I’m really amazed by writers who can capture the other senses, like Upton Sinclair in The Jungle, writing about the Chicago stockyards. He gets the smell. He describes it in a way that in your imagination you smell it too.

BLVR: One final question. As a Buddhist, how do you deal with the reality of evil in the world? I mean, for example, I know you practice nonviolence, but obviously when you face a Putin or a Hitler or a Stalin or a Mao, nonviolence isn’t something they understand.

CJ: That’s the dilemma. I’m nonviolent, but then again, I’m a lifelong martial artist. I truly believe in self-defense. I don’t believe in letting anybody physically violate me or anybody I care about. Now, that is the dilemma for a pacifist. As you said, the problem with bullies is that violence is the only language they understand. The only thing that will stop

them is fear of their own death. If you have to deliver that to them to stop them, to prevent others from being harmed by them, then it’s necessary.

When I collaborated with Steven Barnes on his book of Black horror stories, The Eightfold Path, he asked me if there are any stories about the Buddha killing somebody. I do remember that in all the stories told about the Buddha’s previous lives before he became the Buddha, in one of them he is on a boat with some people, and he realizes one of them is going to kill everybody and rob them. So he kills that person, knowing that he has condemned himself to long rounds of rebirth before he ever achieves liberation. But it was for the sake of the other people that he had to eliminate this robber and murderer. You cannot let evil continue in the world.