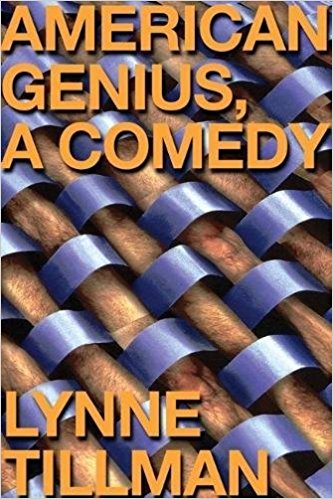

In a study done at Stanford, it was estimated that we have on average 64,000 thoughts a day, and up to 93 percent are repetitions. The repetition of thought lends structure to Lynne Tillman’s stellar new book, American Genius, A Comedy, which, along with being an absorbing work of fiction, also serves as a study of consciousness and memory.

The narrator, Helen, is a neurotic polymath, an Americanist with encyclopedic knowledge about skin, chair design, and textiles (the family trade). She is in residence at an unnamed facility somewhere between an artist’s colony and a mental hospital, preoccupied by various pursuits including burning things, studying Zulu, and contemplating unfurling the Fabric Monolith—a bolt of cloth designed by her father—which she keeps in the corner of her room. She suffers from dermatographia, a condition in which scraping the skin causes weals. It is sometimes called “skin writing.” Problematic skin is the prevailing metaphor of the novel, reminding us that the human condition is both utterly vulnerable—exposed—and claustrophobically subjective. Skin, both public page and protective enclosure, requires constant monitoring and ministration. Helen’s safest intimacies transpire during paid appointments with “the Polish woman,” her cosmetician. She is also fond of her dermatologist, whom she trusts “not to damage me, so that might make a good relationship.” Self-enclosed, if not entrapped, the individual qua self-narrator compulsively marks the involuntary processes and breaches that wrack the bodily vessel, be they welts or thoughts.

While Helen is an accomplished scholar, as the historian of her own life she is thwarted by inexplicabilities. In Proustian, spiraling sentences, she replays, like a broken record, traumatic notes, in particular the incomprehensible killing of her childhood pets by her parents and the mysterious disappearance of her brother. These mental itches, or wounds, function as refrains that digress into scenes of conversation, contemplation, and even a séance, which serves as the novel’s fantastical dénouement. A séance might seem anathema to this character who is invested in all things material, be they skin, cloth, books, or chairs, but, as Helen says, “I’m not willing to doubt everything all the time, because then doubt isn’t doubt, but a form of certainty.”

Throughout Helen’s “residency” at the unnamed facility, she shares meals with fellow residents whose fleshy surfaces she observes carefully, and whose narcissisms, mood swings, and flares of intelligence and beauty are rendered with a deft touch. She names fellow residents after their symptoms...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in