By the time James Lasdun’s second novel begins, with its narrator taking a glass of wine to the face, most of the lies have already been told. The dousing of Stefan Vogel occurs at a party in present-day New York, but its cause goes back to East Germany two decades prior. Like other far-side Berliners of his class, the young Vogel found himself in a tough spot: not wanting to “receive disadvantage” from the watchful authorities while exuding enough artistic integrity to woo women. It was a bind that led him into a sequence of seemingly meaningless lies. But each untruth required the next, and his original falsehood—plagiarizing a secret Walt Whitman volume for an audience he imagines wouldn’t know it—ultimately bloomed into favor-swapping with the government. Though this cooperation earned him a coveted exit to America, his lies have followed him there.

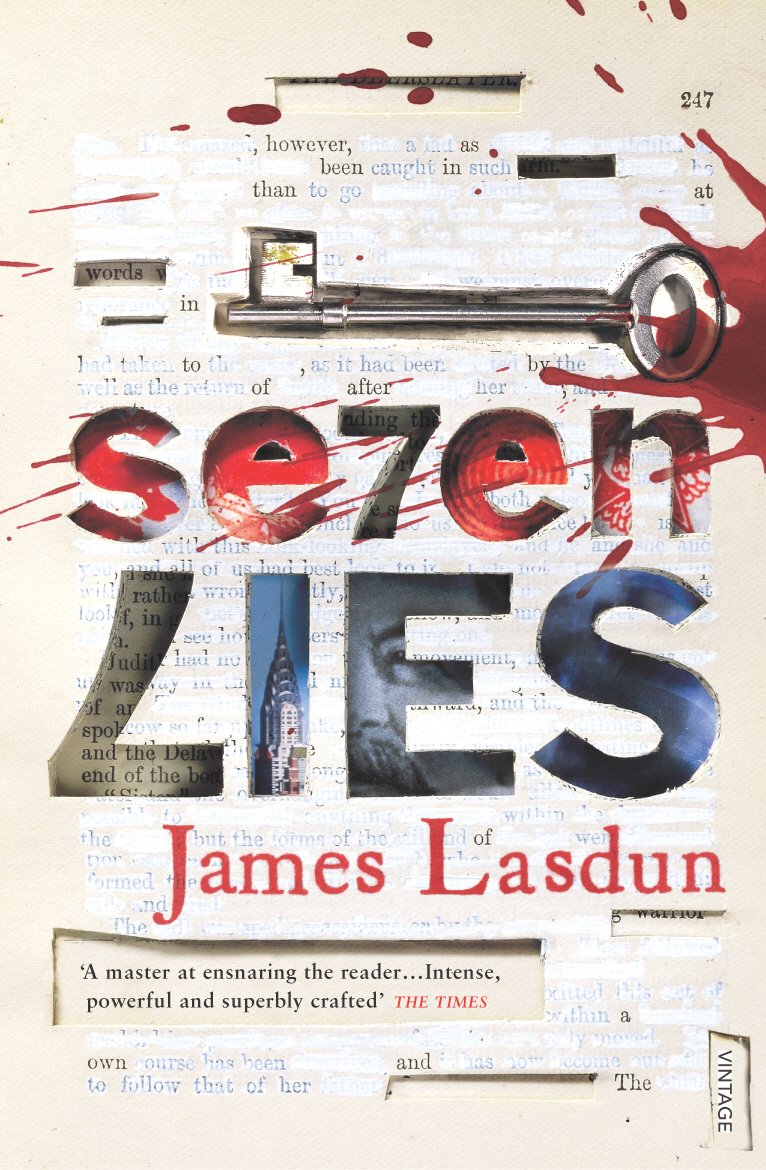

It’s a taut transnational thriller, as told by Vogel. But can we trust his version? According to James Lasdun, an eminent writer with no known history of dishonesty (a lecturer at Princeton, no less), the novel is a study of lies told by a liar; in a world of unreliable narrators, Herr Vogel tops the list.

Under this confounding condition, Seven Lies becomes a larger exercise in narrative: the book’s very subject is its own instability and the wealth of readings that challenge us to perform. Our task is to defeat the narrator—to construct versions that don’t rely on him but instead situate his dishonesty. In that spirit, here are four readings that resist our lying scribe’s, arranged from basic to fancy.

A straight-up morality fable, with shadowy Communist undertones. The novel demonstrates the problems lying causes—even seemingly small lies such as pretending to have been published in a prominent literary magazine. Further, Vogel’s description of “the harm having already been done” when he lies reminds us that not telling the truth is its own punishment. The book also shows how too much lying can lead to getting drinks thrown at you by stoic East Germans, or worse, to murder.

A Soviet propaganda fantasy. The narrator sets up a clever foil: “Criticizing” a regime that has pushed him to lying and tragic consequence. However, we see the strong social bonds formed by these “comrades,” who enjoy a vibrant theatre and café culture in their supposedly “repressive” state. What’s more, only in America does Vogel’s dishonesty manifest itself in violence, and a stained shirt.

A parallel text to Leaves of Grass, in which the protagonist inhabits Walt Whitman’s self-realizing American voice. After Vogel reads from “Song of Myself ”—“I celebrate myself, myself I sing”—the poet’s words enter his speech. He finds his wife incanting the word “Amerika” in her sleep; after settling in the U.S. he moves to the “frontier” just outside NewYork City and begins speaking like his hero—”Astounding, humanless purity of it all!” His lying aligns with Whitman’s image of the American as inventor of self.

A Barthesian collapse of authority. Ultimately Vogel suggests that “America” is not a location but a “prehuman” condition of the mind, and that entering into it thus “requires… the annihilation of oneself.” The parallels to Barthes’s “Death of the Author” are obvious. Having actualized himself as an American in text, Vogel is now effaced. Indeed, now there is only text, and “lying” is impossible. James Lasdun has framed his narrator.

—Theo Schell-Lambert