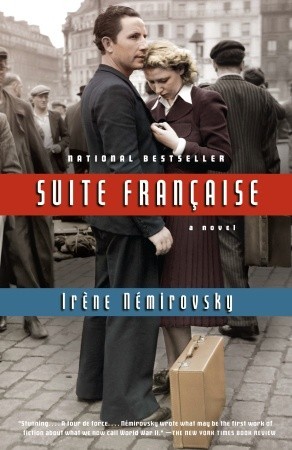

Irène Némirovsky wanted Suite Française to be a five-book cycle about the occupation of France, but only completed a draft of two books before the Nazis sent her to Auschwitz, and to the gas chambers, in 1942. Her manuscript was lost in a basement for sixty years until her daughter, who had been pursued by Nazis through the French countryside as a child, discovered and published it. And now, impossibly, we can read the two books of Suite Française.

The first book, Storm in June, describes the exodus from Paris of every French social caste. Like Proust, another French Jew, Némirovsky explores the tension between the social and private selves, though war, not sexuality, is the fuel for her transformations. She writes in Storm in June that “Important events—whether serious, happy or unfortunate—do not change a man’s soul, they merely bring it into relief, just as a strong gust of wind reveals the true shape of a tree when it blows off all its leaves.” Thus does the paranoid aristocrat Langelet, who feels “scandalized” by the “real world full of unfortunate people,” transform into a thief, admitting he’d “never felt such exquisite pleasure” as he felt after stealing. A condescending priest, Father Péricand, is likewise revealed; the juvenile delinquents in his care turn out to hate him even more than he hates them. And Péricand’s bossy mother, whose family is collapsing, fights her vanity in the chaos of the exodus. Characters’ lives are changed, half by war, and half by energies germane to their own selves. They are both trapped by history and independent of it.

The second book, Dolce, contained in the same volume as Storm in June, explores how occupation forces people—both conquerors and conquered—to confront their disappointments. Lucile, whose husband has been captured, is drawn out of both maternal concern and out of love to the lonesome Nazi who has occupied her house. Némirovsky is generous enough to make Nazis look decent—which is incredible, when you consider how she died—but this is the novelist’s job, to make us see things which our prejudice and habits make invisible.

Lucile’s village is plagued by more of Némirovsky’s wonderful hypocrites, like Vicountess de Montmort, whose charitable works conceal her hatred of the poor. “She… forced herself to kiss the children… who were all fat and pink, overfed and with dirty faces, like little pigs.” When this most unphilanthropic philanthropist says of the villagers that “you have to go to so much trouble to instill a glimmer of love into these sad souls,” we see the flicker of a character who might’ve equaled Mme Verdurin.

Némirosvky writes exquisite descriptions. When Mrs. Péricand is reunited with her son Hubert, she thinks, “Hubert, who failed miserably at school, who bit his nails, Hubert with his ink-stained fingers, his lovely chubby face, his wide young mouth, for Hubert to die a hero was… inconceivable.” And the Péricand cat does not just kill a bird, it delicately unifies violence and affection: “He had plunged his claws into the bird’s heart and clenched and unclenched his talons, digging deeper and deeper into the tender flesh… with slow and rhythmical movements until its heart stopped beating.”

Even in its embryonic state, Suite Française is a masterpiece that may join such books as The Painted Bird, The Periodic Table, and Night in the canon of humanistic war literature.