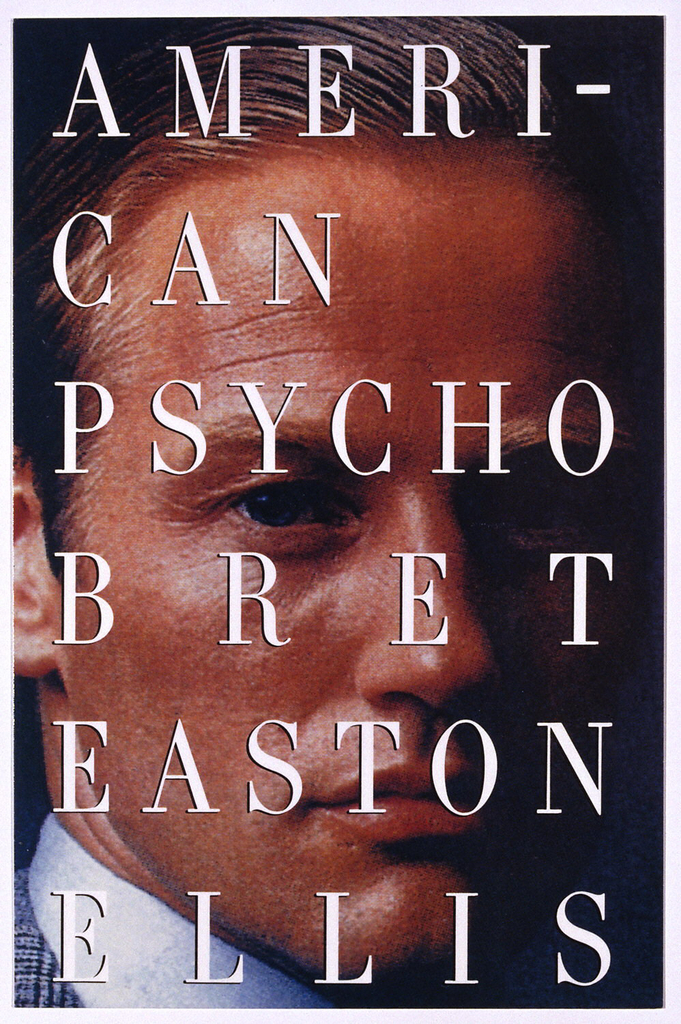

Along with nearly all of his readers, Bret Easton Ellis had trouble with the violence in American Psycho. Even in his quasi-autobiographical novel, Lunar Park, published almost fifteen years later, the character “Bret Easton Ellis” is haunted by guilt over Patrick Bateman, the mass-murdering character he created. But Ellis also had trouble with American Psycho’s violence while writing it: the murder scenes remained unwritten until the rest of the book was completed, at which point Ellis read FBI criminology textbooks detailing actual serial killings and returned to insert the scenes that would be most unsettling to author, reader, and public alike. “I didn’t really want to write them,” he told an interviewer later, “but I knew they had to be there.”

What this leaves us with is violence that is mostly self-contained in a handful of brief chapters. To remove that violence would more or less be a clean excision, leaving the rest of the savagely insouciant satire intact. What’s more, the themes and dynamics in the novel would remain as they are; with a single exception, there is nothing in the plot that would be hindered by the missing chapters. Twenty years after the sensational publication that brought on a hysteria of denunciations, the loss of a publishing deal, and death threats against the author, the offending passages may not, after all, be necessary. But would we have a better novel—not just a more comfortable novel—without them?

This would be a thin-skinned exercise if the carnage were not so appalling. (The gore was drastically skimped in the 2000 movie.) Consider, as a token of the novel’s atrocity, that many victims lose consciousness while losing portions of their bodies: while Bateman is sawing off their legs or exploding their breasts, their eyes (if they still have eyes) are closing. It’s too much strain for a human being to endure; consciousness closes down in defense. And it’s likewise too much for the reader: we begin chapters with names such as Tries to Cook and Eat Girl with a queasy foreboding, as though something is about to go horribly wrong in our own nonfictional lives. We begin a chapter entitled Killing Child at Zoo unsure that we want to read any further.

And so this is what the novel has condemned itself to being known for: the carving-up of bodies (particularly women’s bodies) rather than unique and brilliant social satire. The main accomplishment of the novel—its tremendous humor—gets obscured during the anxious wait for the next bodily evisceration. After reading about a person’s lips being snipped off, you feel complicit if you laugh at something on the next page.

If American Psycho has a thesis, it’s that certain types of people are so obsessively set on outward perfection that they miss the real substance of being human. Money and beauty insulate these people from regular needs but create a hypertrophied rivalry over status: the novel’s characters boast of paying more than they really did; they seek relationships for show rather than companionship. When Bateman continues his exhaustive detailing of designer clothes while tearing apart the body of a sentient human being, he’s showing us where a culture of vanity takes us: to a place where the label matters more than the person.

This would thematically justify the violence—as a ruthless way of showing how little other human beings matter to the type that Bateman represents—if the novel didn’t provide this perspective already. But it does: on every single page this culture is mocked in thoughts and dialogue that have little need of physical manifestation. In one scene, Bateman listens to his friends guffaw about how “the only girls with good personalities who are smart or maybe funny or halfway intelligent… are ugly chicks.” He then spoils their prickish fun by referencing someone else who also had a highly reductive view of women: he quotes a serial killer who says he wants to do two things when he sees a pretty girl—“take her out and talk to her and be real nice and sweet,” then see “what her head would look like on a stick.”

You don’t need to see an actual beheading to appreciate the blunt commentary. Similarly, Bateman can play the “tease-the-bum-with-a-dollar trick” without also jamming a knife into a different bum’s eye. He can leave a teddy bear for a girlfriend that he’s just pressured into an abortion without also releasing a rat into the upper regions of another woman’s reproductive organs. The conclusions are already on display. Consequently, as a reader, you are absolutely free to skip those chapters in which life is stubbed out. They are: Tuesday, Killing Dog, Lunch with Bethany, Killing Child at Zoo, Rat, Tries to Cook and Eat Girl, Working Out, and all other chapters with girl in the title. You can tough it out through the few stray killings that remain, which provide some of the slight plot.

When you finish this self-abridged version, you may well be just as unsettled by the novel’s blithe nihilism—the unappeasable boredom, the oblivious entitlement, the disgust with imperfection—as if you’d read through all the slashings you’ve just skipped. But you’ll probably have laughed a great deal more, and the richness of Ellis’s satire will probably stay with you longer now that it isn’t competing with nausea.