David Foster Wallace’s 1993 essay “E Unibus Pluram” concludes by suggesting that the next wave of literary rebels in the U.S. “might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels… Backward, quaint, naïve, anachronistic. Maybe that’ll be the point.” After all, in our fearful, insincere age, what could be more radical and risky than spinning a good old-fashioned yarn?

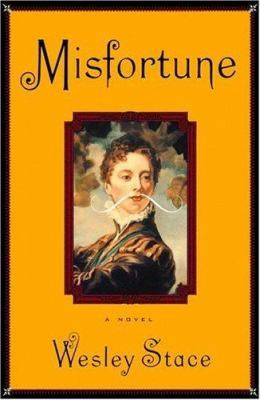

While Wesley Stace is not quite American—he’s British, but he’s lived here for fifteen years—his amazingly accomplished debut novel is precisely the kind of rebellious anachronism that Wallace augured. In its premise, plot, pacing, style, and enormous cast of characters, Misfortune operates deliberately like a Dickens novel. The book begins with a foundling in a rubbish heap (a foundling!), taken home to opulent Love Hall by the bachelor Lord Geoffroy Loveall, who, because of the traumatic early death of his sister Dolores, is determined to raise the child as a girl (Rose Old), even though the child is a boy.

Rose enjoys an idyllic girlhood at Love Hall, one of the most splendid homes in nineteenth-century England. She has a loving father and mother (for the sake of appearances, Lord Geoffroy quickly weds Anonyma Wood, the governess-turned-librarian), as well as playmates, books, and beautiful grounds. Not only does Rose think he’s a girl, in many ways he is a girl. This preoccupation with identity and the social construction of gender is one of the ways that Stace slyly updates the Victorian novel’s concern with nature/nurture.

Two events conspire to end Rose’s blissfully ignorant youth at Love Hall. First, puberty. Second, the Loveall’s scheming, avaricious relatives begin swooping and snooping in order to discredit Rose’s claims to Love Hall. Ultimately, Rose and the Lovealls are banished, and if the first half of Misfortune is a domestic novel, the second half is its opposite, the adventure novel. Rose travels the world before making her way home, and while the late unfolding of the plot is predictable to anyone who has ever read a foundling novel, there is pleasure and surprise in the how, if not in the what.

As impressive and complicated as this plot is, Stace’s most remarkable feat is tone. The novel is witty and moving, and at no point succumbs to flimsy parody or satire. This is not a foundling novel that pokes fun at foundling novels, which would have been the more fashionable book. Stace writes with conviction and an earnest commitment to his main character and his/her troubles, and the result is a refreshingly old-fashioned story.

And yet for all of its ancient notions of plot and character, Misfortune feels contemporary and even edgy, with its fluid notions of identity and gender, and its thrillingly filthy scenes (who knew foundlings have cocks?). The novel also has its postmodern touches: a point of view shift on page 75, an appendix in the form of guidebook excerpts, and a penchant for anagrams, cryptograms, circuits, and codes.

It’s fitting that this novel of identity and Ovidian transformation should be written by Stace (a.k.a. John Wesley Harding), a folk/pop musician who has released more than a dozen CDs. In a song called “Bastard Son,” Harding stakes out his artistic family: “Bob Dylan is my father, Joan Baez is my mother, and I’m their bastard son.” Stace the novelist seems to be the product of a less conventional union—perhaps Dickens and Nabokov—but it’s pretty clear that Dickens was the primary caregiver.